Why Latino voters have such a misunderstood stance on abortion.

Part of The power and potential of Latino voters, from The Highlight, Vox’s home for ambitious stories that explain our world.

Alba has never been in a situation where she had to consider an abortion, even during four high-risk pregnancies. And the Latina mother of five from Dodge City, Kansas, doesn’t know what she’d do if she were in such a situation.

“Even if I don’t agree with it for myself, I’m not going to get in the way of somebody else seeking health care,” said Alba, who was raised Catholic and asked to be identified only by her first name because of the stigma around abortion in her conservative community. “The decisions that I make for myself are for myself only.”

So she had no hesitation about voting against a proposed constitutional amendment on the Kansas ballot in August that would have allowed state lawmakers to further restrict abortion access in the wake of the US Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade.

The amendment failed by a surprisingly large 18 percent margin. Its demise was bolstered by the results in Kansas’s four Latino-majority counties — Finney, Ford, Seward, and Grant — all of which are in the state’s rural southwest region and voted for former President Trump by margins of at least 24 percent in 2020. Each was expected to support the amendment. But the results were much closer than anticipated in three of those counties — in Finney and Ford counties, the margin was just 4 points, and in Seward, it was 50-50.

The referendum’s defeat was the first real glimpse into how Latinos might be reacting to the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe ahead of the midterms. Republicans have heralded a great political realignment of Latino voters for years, claiming that the GOP is a more natural fit for their conservative Christian values. And it’s true that Latino support for Republicans grew in 2020. But given the results in Kansas and in recent national polling, Republicans’ efforts to further curtail abortion rights may do more to alienate Latinos than to attract them.

“This was not a net positive for the Republicans. It does rile up evangelical constituencies, but they had their voters anyway,” GOP strategist Mike Madrid said. “Republicans should be focused exclusively on inflation in the economy. Pretty much every other issue is to their detriment. I would much rather be Democrats at this point in the election cycle than Republicans.”

The results of the referendum are in fact energizing Democrats, at least according to Alejandro Rangel-López, an organizer who advocated against the amendment in Latino neighborhoods in Ford County.

“People my age, especially out here in southwest Kansas, were super excited by the results that we were seeing coming out from this region and the potential for other things — to elect progressive people to the city commission or make change on the school board,” Rangel-López said.

The amendment failed despite big spending from anti-abortion causes. Rangel-López said the Catholic Diocese sent out thousands of mailers trying to get their members to vote for the amendment. About 60 to 70 percent of Dodge City residents are Catholic, he estimated, and among US Hispanics — who include people from Spanish-speaking countries in addition to those from Latin America — it’s exactly half. (Most demographic data measures Hispanics, not Latinos specifically, but the vast majority of Hispanics in the US are Latinos, so the terms are often used interchangeably.)

In his conversations with voters, it was clear in many cases that they personally were against abortion. But much like Alba, many Latinos he spoke with also didn’t support further curtailing access to the procedure, which is already heavily regulated in Kansas, a state that has become a key safe haven for abortion in the Midwest.

“Morally, yes, there’s like a stigma and folks don’t agree with it. And it’s viewed very, very negatively,” Rangel-López said. “The general attitude that folks have is, ‘I don’t agree with it, but it should be their choice.’”

Latinos are religious — but that doesn’t mean they’re anti-abortion

A common misconception is that because such a large proportion of the Latino population is Christian, Latinos are more likely to oppose abortion. Pollsters and strategists for both parties say that’s a myth for three reasons: Latinos aren’t as Christian as they once were, most Latinos don’t belong to Christian sects that advocate for political anti-abortion policies, and there are numerous factors beyond religion that shape Latino views on abortion.

A shrinking share of US Hispanics identify as Catholic. That share stood at 50 percent as of 2020, down from 57 percent in 2009. About 14 percent identify as evangelicals, making Hispanics the fastest-growing group of American evangelicals. All told, 76 percent of Hispanic Americans identify as Christian, per the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI), compared to 71 percent of white Americans.

The fact that Catholicism is the most prevalent denomination of Christianity among American Hispanics is an important distinction: Among many Catholics, and Hispanic Catholics in particular, religion doesn’t dictate one’s views on abortion. That’s in contrast to evangelicals, many of whom see the US as a Christian nation and believe that its laws should be shaped by the Bible.

“To follow Catholicism has never been a socially conservative anchor for our politics,” Madrid said of Latino voters. “There tends to be a more ambivalent view of culturally conservative issues amongst Catholics.”

That’s consistent with a July PRRI study of Hispanic voters, which found that 66 percent of Hispanics overall support abortion in most or all cases and 72 percent of Hispanic Catholics opposed the overturning of Roe. Less than a third of Hispanic Catholics say their religious faith dictates their views on abortion, and only 13 percent say they look to religious leaders for guidance on how to think about abortion.

Big majorities of Hispanic Catholics also oppose making it a felony to seek or provide an abortion, laws that make it illegal to cross state lines to obtain an abortion in another state, and restricting abortion to cases where it’s necessary to save the life of the mother.

In an August Mi Familia Vota/UnidosUS poll of Latino eligible voters, respondents were asked whether they agreed with the statement, “No matter what my personal beliefs about abortion are, I think it is wrong to make abortion illegal and take that choice away from everyone else.”

Among Catholics, 76 percent agreed, and 58 percent strongly. And even among Republicans, 55 percent agreed and a third strongly.

For the first time ever, Latinos also ranked abortion as one of the top five issues facing the country — behind inflation and the rising cost of living, crime and gun violence, jobs and the economy, and health care.

“When people say that they’re against an abortion, what they typically mean is that they don’t think they would have one and they don’t think someone in their family would have one. But there is still, for that same voter, a wide range of empathy and understanding for other people,” said Matt Barreto, a professor at UCLA and the co-founder of the research and polling firm BSP Research, which conducts polling for the Democratic National Committee and the White House.

Latino evangelicals are generally more conservative than Latino Catholics on policy issues. Rev. Gabriel Salguero, the president and co-founder of the National Latino Evangelical Coalition, described evangelicals as “pro-life from womb to tomb,” meaning they’re against both abortion and the death penalty, and want to see more investment in programs that support families raising children.

Salguero himself does not identify with any political party, and while he emphasized that Hispanic evangelicals are “not one-issue voters,” he also said abortion is “not a small issue for Latino evangelicals.”

Still, polling suggests that evangelicals are still pro-access, even if they wouldn’t choose abortion for themselves. In the Mi Familia Vota/UnidosUS poll, 68 percent of non-Catholic Christians, including evangelicals, didn’t support the government revoking the right to an abortion.

“We have a nuanced view of what it means to be pro-life,” Salguero said.

It’s not just religion shaping Latinos’ views on abortion

For many white Americans, particularly white evangelical Americans, views on abortion are primarily an outgrowth of religious beliefs.

The prominent evangelical leader Rev. Franklin Graham has made that connection explicit, saying after the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe, “My prayer is that every state will enact protections for children in the womb and that our nation will value life and recognize the rights of our most vulnerable.”

But Latino Americans have views shaped by numerous factors.

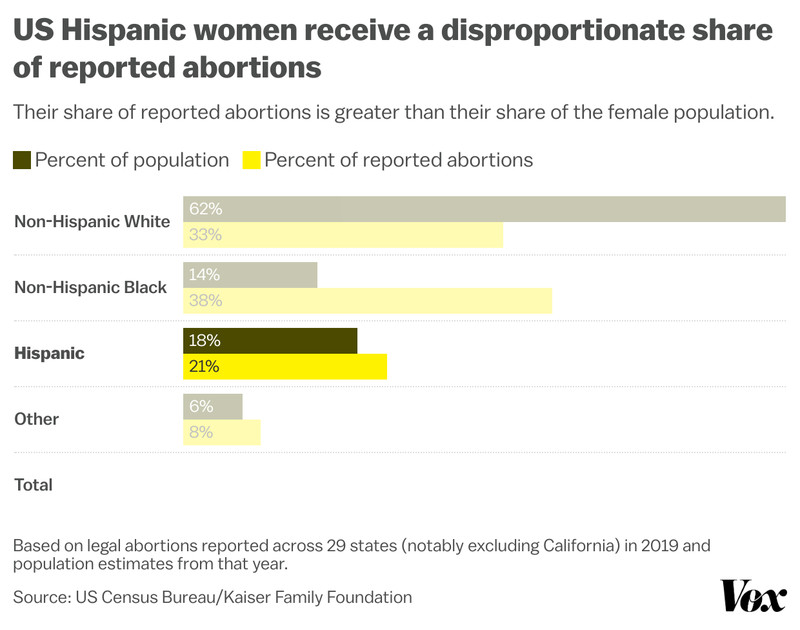

For one thing, Latinos have a direct familiarity with abortion services not necessarily shared by other communities — they receive abortions at a disproportionate rate.

Though they made up 18 percent of the US population in 2019, Latinos received about 21 percent of the total legal abortions reported across 29 states that year. (That number does not include California, home to the largest Latino population in the US, which does not report abortion figures.)

By comparison, Black people, who made up 12.5 percent of the population, accounted for 38 percent of reported abortions, and for non-Hispanic white people, who made up about 60 percent of the population, it was 33 percent.

Part of that has to do with age: Latinos are much younger than white Americans, with an average age of 28, compared to 43 for white Americans. More Latino Americans may seek abortion care — and may be more affected by abortion bans — simply because a greater proportion of them are in their prime reproductive years. Younger Latinos certainly appear very concerned with access: Pollsters have found a higher level of support for abortion among Latinos under the age of 35.

Elizabeth Estrada, a field and advocacy manager in New York for the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice, says there’s another major factor. She attributes those disproportionately high abortion rates among Latinos in part to their poor access to preventive health care, which includes sex education and family planning services.

For Estrada, who immigrated to the US from Mexico, sex wasn’t a subject that was brought up in her childhood home. The extent of what she learned in school was how to put in a tampon and the male and female anatomy. So she was surprised when she got pregnant at 21 after not using a condom one time with her partner, even though he hadn’t fully ejaculated, she says.

She ended up getting an abortion in Georgia, and every aspect of the process was secretive by design. She initially refused her family doctor’s offer of a pregnancy test because she didn’t want her mother to find out. The abortion clinic she went to had blacked-out windows to deter prying eyes. No one spoke to each other during the seven hours she spent in the clinic waiting room, not even to comfort a girl who was crying.

“We didn’t feel empowered enough to speak. And it was that silence that really pissed me off. Because I’m just like, why is this so stigmatized? Why do I feel bad about [a procedure] that took 15 minutes?” Estrada said. “That was how I became activated.”

Now the overturning of Roe threatens to make it harder for Latinos to get access to abortion and reproductive health care than it already was. And that’s made abortion a matter of personal concern for many.

Texas, which is home to the second-largest Hispanic population in the US after California, began restricting access to abortion even before the Supreme Court’s decision. Last year, Texas passed SB 8, which banned abortion for most women after six weeks and set up a kind of bounty hunter system that let anyone sue doctors for performing abortion procedures, or even aiding them. It prompted widespread backlash, including from Latinas in the state.

“Texas was at the forefront of this fight,” Barreto said. “Latinos were very much exposed. Some of those early sob story cases that were being reported were of young Mexican American [women] trying to get an abortion. It’s no longer a hypothetical. For many Latinos, it’s very real.”

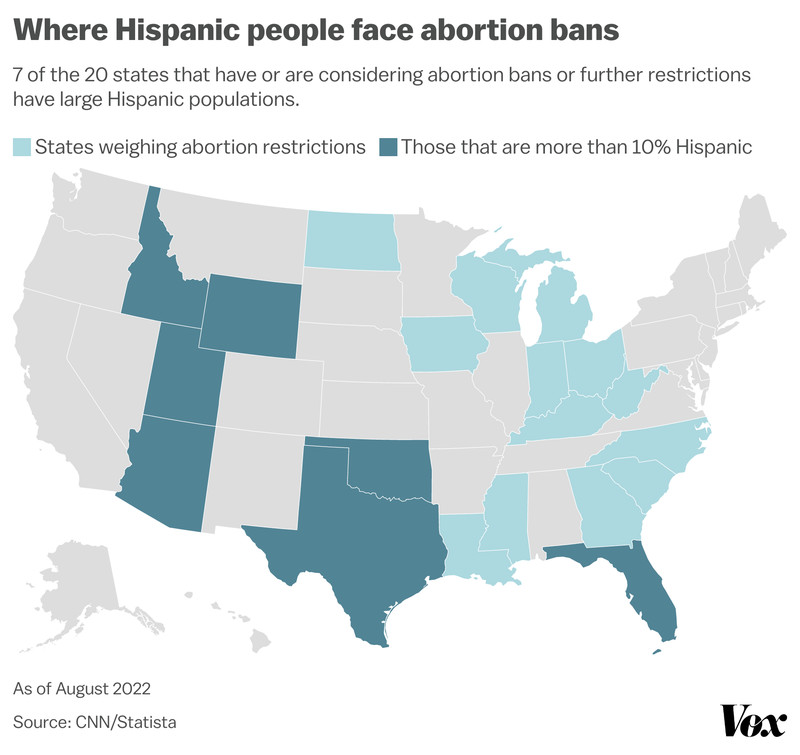

Now, seven of the 20 states where legal fights are underway over abortion bans and other laws that severely limit the procedure are states where Hispanics make up at least 10 percent of the population, and in five of those states, they number at least 1 million.

Most states that already have or are considering abortion bans have exceptions for cases where the life of the pregnant person is at risk. But there are still concerns that maternal health will suffer. Those are even more acute in Hispanic communities; a Blue Cross Blue Shield Association report found that women in majority-Hispanic communities already had a 32 percent higher rate of maternal morbidities than women in white majority communities in 2020.

Through familial ties, and sometimes through personal experience, many Latino Americans have a keen awareness of what it’s like not to have abortion access.

“A lot of Hispanics come from countries where abortion is still illegal. They’re very much aware of what having no access to reproductive services is like,” said Rangel-López, who said that invoking language associated with the feminist movement in Latin America helped him convince some Kansas voters.

A growing number of Latin American countries have loosened restrictions on abortion in recent years. Since Argentine lawmakers voted to legalize the procedure in 2020, Mexico’s and Colombia’s highest courts have decriminalized abortion, Ecuadorian lawmakers made abortion legal in cases of rape, and Chilean lawmakers began seeking to guarantee women’s reproductive rights through the country’s new constitution.

That’s not to say that people in those countries have progressive views on abortion, but attitudes are changing. In Mexico, for instance, nearly a third of the population supported legalizing abortion in all cases in 2019, compared to just 12 percent in 2005. And now, Americans are increasingly going to Mexico to access abortions in the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe.

Those changes could influence the views of Latinos in the US. It’s true that the most culturally conservative constituency of Latinos is recent immigrants who “bring that culture and values with them,” Madrid said. But the distinct leftward shift on the issue in Latin America could contribute to a growing pro-choice Latino constituency in the US.

“It’s a much more progressive environment, at least from a government perspective and legal perspective,” Madrid said. “It’s not viewed as a government issue.”

Neither party can count on abortion to win over Latino voters in the fall

National Democrats are telling their candidates to run on Roe. There’s some disagreement about how heavily Democrats should focus on abortion when speaking to Latino voters, however. Sisto Abeyta, a Democratic strategist in New Mexico, said that it would be a “big, big mistake for anybody who wants to get the Latino vote in America today to think that they can do it based on one issue.”

But others think the results in Kansas changed the calculus. Chuck Rocha, a Democratic strategist and former adviser to Sen. Bernie Sanders’s 2020 presidential campaign, said he was skeptical that Roe would motivate Latino voters after Rep. Henry Cuellar, the last remaining anti-abortion Democrat, fended off a progressive challenger in a majority-Latino district in south Texas earlier this year.

“Early on, I was a little more cynical,” he said. “The Kansas election was a real wake-up call for me. And then in focus groups and polling that we’ve been seeing, Roe is now a much more powerful issue than I even gave it credit for early on.”

Political scientist Ruy Teixeira said Democrats would be wise to emulate the approach in Kansas — where pro-abortion rights organizers described the amendment in terms of government overreach — rather than affirmatively advocating for fewer restrictions on abortion.

“Wherever Republicans are trying with outright bans, you hammer them on this,” he said.

But it’s still not Latino voters’ top priority, and that leaves an opening for Republicans.

“Everything I’ve seen suggests that jobs and the economy are always right there at the top for those moderate gettable swing voters,” said Brendan Steinhauser, a GOP strategist based in Texas. “You’re going to see more of an economic argument and upward mobility argument from Republicans with moderate and independent Hispanics.”

To this end, Rocha said the end of Roe should be part of a broader message that Democrats should be delivering that makes Roe a top priority but also speaks to Latinos’ other concerns.

“You have to bring up Roe and the sanctity of what a woman has the right to do or not do in their body, and then add in what the Democrats have delivered in this Congress, which has been historic. Our strategy should be Roe. It can be Roe first, but it should be Roe plus,” Rocha said.

Alba has voted for both parties in the past, and even though she supports abortion rights, she registered as a Republican during the Kansas primaries so that she could support more moderate candidates over their extreme right-wing opponents. She said she’s keeping an open mind with respect to which party she will support in the general election.

“On abortion, yeah, I do lean left,” she said. “But in my opinion, it’s somewhat dangerous to just vote down the party line. You could be voting for someone that’s going to be working against the population, against their best interests.”

----------------------------------------

By: Nicole Narea

Title: Yes, most Latinos are Christian. No, that doesn’t make them anti-abortion.

Sourced From: www.vox.com/the-highlight/23322487/abortion-latino-voters-roe-midterms-election

Published Date: Tue, 20 Sep 2022 10:42:49 +0000