The history of warfare abounds in surprises. Underdogs win conflicts. Forces triumph without having had the most troops, the best equipment, or even control of key cities and territories at the outset. But one ingredient always matters. In our research of wars of all kinds since World War II, we found that the key to winning is sound strategic leadership.

What exactly is sound strategic leadership? As we examined in writing Conflict","_id":"0000018b-3dba-d77d-a38f-fffe9cc00000","_type":"02ec1f82-5e56-3b8c-af6e-6fc7c8772266"}">Conflict, good strategic leadership — that at the very top of a government and a military command — has to be both practical and visionary. Big ideas are at its core, and getting them right is of paramount importance; without the right big ideas, all else will be built on a shaky intellectual foundation. Hence, a strategic leader’s first task is to develop those big ideas, ones that reflect an astute understanding of all aspects of the conflict at hand.

In the case of the first Gulf War, for example, the biggest of the big ideas was both simple and profound: “This will not stand,” President George H.W. Bush declared of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. And with that, the military leaders had their marching orders and set about developing the other big ideas that guided the subsequent campaign.

After getting the big ideas right, strategic leaders have to perform three other crucial tasks. They must communicate their vision of the big ideas, of the campaign they intend to conduct, not only to their fighting forces on the ground, but also to coalition partners and all others invested in the outcome of the conflict. They then have to oversee the implementation of those ideas and ensure that they are translated into appropriate action on the ground. And then they have to determine how the big ideas need to be refined and adapted in order to perform the whole process again and again.

But it all starts with getting the big ideas right; failing to do that typically dooms what follows.

As Benjamin Netanyahu contemplates his options for punishing Hamas for the worst single massacre of Jews since the Holocaust, he must above all, provide sound strategic leadership, performing the four tasks of a leader at the very top — and, above all, getting the big ideas right.

For all that Netanyahu might today feel that his big idea must be the utter elimination of Hamas as a militant group, he must also develop additional big ideas that will be important to his own citizens, Palestinians who are not members of Hamas, the wider Jewish diaspora and the friends — and critics — of Israel around the world.

This first big idea, the destruction of the militant group Hamas — its bases, headquarters and facilities — and capturing or killing the bulk of its leaders and terrorist fighters (who do not wear uniforms and locate among innocent civilians) will be a fiendishly difficult task, as hard as that of any endeavor in the period we examined in Conflict, given the 2.4 million people in Gaza, density of the high rise buildings, the presence of approximately 200 hostages, and an expectation that Hamas will employ booby traps, improvised explosive devices and suicide bombers.

Netanyahu’s formation of a national unity government and a war cabinet are a good first step as the Israeli government and military come to grips with how to “operationalize” the task of destroying Hamas, but they and the Israeli high command now need to determine specifically how to unleash the IDF and its 360,000 reservists (not all around Gaza, to be sure) into the 140 square mile area of the Gaza Strip. Nor do Netanyahu’s worries end there. For as well as his promise to “wipe this thing called Hamas off the face of the Earth,” Netanyahu must also adhere to other big ideas, including observing the Geneva Convention — “purity of arms” in the Israeli construct — in an enormously complex tactical situation in a densely built-up area; try to rescue hostages who are presumably now widely dispersed around the Strip; not lose the sympathy of world opinion by indiscriminate action; shore up the Abraham Accords; not inflame those in the West Bank any more than is already the case; dissuade Hezbollah from firing into Israel large quantities of the 150,000 rockets stockpiled in southern Lebanon (and respond as appropriate); deter Iran and Syria from getting directly involved (or using proxy militias in Iraq, Syria and Yemen); prevent Israeli Arabs from undermining security within Israel; keep economic and military aid flowing from the United States of America; and describe a way forward for the Palestinian people, making clear that Israel’s war is not with them but with the terrorist groups that are living among them.

The “big idea” for Israel to offer ordinary Palestinians who are not members of Hamas might include a resuscitation of the two-state solution, in which they are offered their own state, despite the two obvious pitfalls to any actual implementation of that in the short to medium term. The first is that Hamas will only accept a one-state solution by which the Jewish State of Israel is destroyed and the second is that the split between Hamas in Gaza and Fatah in the West Bank means that no unitary Palestinian state is currently viable. Needless to say, the situation in the West Bank has also been intractable for many years, as well. Were Netanyahu somehow able to square these seemingly impossible circles, he would emerge as one of the greatest statesmen of the modern Middle East. Nonetheless, he would be wise to provide a vision of the future for those in the West Bank, as well as Gaza, as he also describes the mission he is assigning the Israeli Defense Forces.

Our examination of the wars since 1945 reveals, again, that the situation facing Netanyahu may be the most challenging and complex of all those we explored, but it is still worth revisiting past cases of strategic leadership, both good and bad, in the post-World War II conflicts to see what the Israeli prime minister might be able to learn from the past.

British General Sir Gerald Templer, for example, was a strategic leader par excellence as Britain’s high commissioner in charge of the Malayan Emergency from 1952 to 1955. Placed in command of a colony riven by communist guerrilla warfare, Templer made clear Britain’s commitment that Malaya would be granted independence as soon as the security situation allowed. He developed a masterful military campaign that was continued by his successors. By 1957, Malaya was independent, and by 1960, the campaign had quelled the communist insurgency. In carrying out this mission, Templer never underestimated its difficulty. “I have always said that the complete cure of it all will be a long slog,” he remarked in 1953. He could be harsh — he more than earned his popular sobriquet “the Tiger of Malaya” — but as he told Oliver Lyttelton, the colonial secretary, in November 1952, “The shooting side of the business is only 25 percent of the trouble, and the other 75 percent lies in getting the people of this country behind us.”

Templer’s experience — and that of the coalitions in Iraq and Afghanistan in the wake of the 9/11 attacks — remind us of the question that should always be asked before operations are conducted: “Will this operation take more bad guys off the street than it creates by its conduct?” Needless to say, that question looms over the campaign Israel is contemplating for Gaza.

Templer’s call for winning “hearts and minds” — a very big idea — has so often been cited as to become a cliché in the decades since. Nonetheless, that concept remains the most succinct explanation for how to win a counterinsurgency. Templer’s leadership, from determining the right big ideas through communication to execution — and then adaptation — was the most important element in the success of the campaign. Underlying it all was the big idea that Malaya would become an independent country once the Emergency was over and the Communist terrorists were defeated. While Netanyahu will certainly struggle to win Palestinian hearts and minds, he could offer them an independent state once, as he has put it, “Every Hamas member is a dead man. We will crush and destroy it.”

If Netanyahu needs examples of successful Israeli leadership in the past, history is replete with them, especially in the country’s early wars. In the 1973 Yom Kippur war, Israel was taken by surprise and put in a desperate situation. It nonetheless defeated several much bigger, more heavily armed adversaries with a brilliantly led, lightning quick, audacious campaign that became the subject of obsessive study in Washington afterward. Weapons still mattered; the Yom Kippur war demonstrated the continued salience of tanks despite devastating new anti-tank guided missiles, as well as the importance of air defense missiles and modern aircraft. But it also demonstrated, in the words of the Israeli diplomat Michael Herzog (who is now ambassador to the United States), “the extent to which man is the key to the outcome of war. The training and skill of the soldier, his motivation, the quality of the chain of command, initiative, courage, and perseverance all underlie the War’s result far more than any weapons.”

Central to the success of the Israeli counteroffensive in 1973 were big ideas that included a willingness to take risks in responding to a desperate situation and promoted the exercise of initiative at all levels. In a tenuous, dynamic situation, Israeli commanders figured out what needed to be done and executed it aggressively. But the successful counter-offensive was carried out in areas much less challenging than Gaza, with vastly fewer civilians on the battlefield, against largely conventional military forces that were easily identified.

The war, as much as it briefly posed an existential threat to Israel, ultimately resulted in resolutions that ensured considerably better security for Israel with its Egyptian neighbors and an arrangement with Syria. But another difference from today is that, back then, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger could call leaders in each country — in Egypt, Syria, Jordan and Israel — and broker a deal. Doing so with Hamas is not only practically impossible — how could a conversation be had with the leader of a barbaric entity the U.S. has designated a terrorist organization and is certain not to engage in serious dialogue? It is also implausible as Hamas adamantly refuses to recognize Israel’s right to exist and is determined to destroy it.

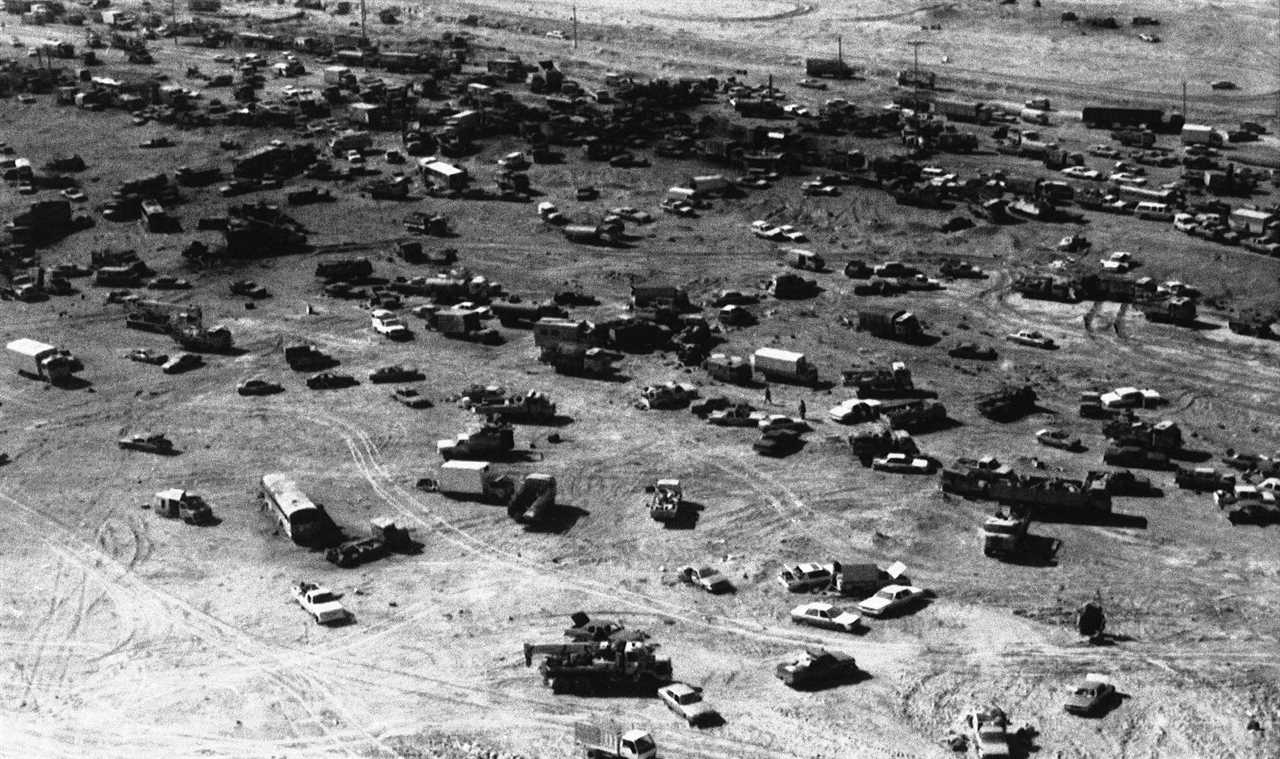

In waging the Gulf War in 1991, President George H.W. Bush, General Norman Schwarzkopf and Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Colin Powell presided over forces that had learned important lessons from the Yom Kippur War about various weapons systems and the conduct of warfare in a generally desert setting. With the president’s clear guidance at the outset — that Iraq’s invasion of its sovereign neighbor would not be tolerated — the civilian and military leadership of the United States immediately set about defending against any Iraqi attempt to seize Saudi oil fields, galvanizing international support, building a substantial coalition of forces and then expelling Saddam Hussein’s troops from Kuwait.

Powell envisioned mounting a force so decisive in its scale that Baghdad would either be intimidated into compliance or face certain defeat. To that end, the United States brought together a coalition that deployed overwhelming capabilities to Saudi Arabia and the Gulf — and then increased the forces even further. The coalition established air supremacy and pummeled Iraqi forces from the air for 39 days, making superb use of precision munitions, and then used weapons systems developed in the wake of the Yom Kippur War to defeat Iraqis forces and liberate Kuwait in a 100-hour ground campaign. But, as with the Yom Kippur War, the context was incomparably less challenging than what faces Israel in Gaza.

Twelve years later, the United States fought a second war in Iraq that threw the strategic leadership of the 1991 Gulf War into stark relief. The context was more challenging, as the United States struggled to find sufficient partners both in Iraq and in the region. But confusion about the big ideas guiding the conflict was also a major problem. Washington acted on flawed intelligence regarding the Iraqi possession of weapons of mass destruction, then toppled Saddam Hussein’s regime with impressive rapidity, only to find that the plans for the post-conflict phase were sorely inadequate. Instead of setting up an embassy and a four-star military headquarters at the outset (though it did so later), the United States established the Coalition Provisional Authority — a pickup team that would oversee Iraq for the first year or so, with many members who served for no longer than three months before rotating home.

Two misguided early decisions, seriously flawed big ideas, would haunt the U.S. effort for many years: Firing the Iraqi military without a plan to enable the former soldiers to provide for themselves and their families, and also firing tens of thousands of Ba’ath Party members down to a level that eliminated the experienced (often western-educated) bureaucrats needed to run a country whose leadership had been decapitated.

These missteps were subsequently addressed, and progress was made, until the Sunni extremist bombing of a sacred Shia Shrine in February 2006 propelled the country into sectarian civil war, which required the United States to change its military approach dramatically. The Surge of 2007-08, which drove violence down by nearly 90 percent, allowed Iraq three subsequent years of relative calm. Yet within 24 hours of the withdrawal of the final U.S. combat forces in October 2011, the Iraqi prime minister undertook highly sectarian actions that alienated the Sunnis and tore apart the fabric of a society that coalition and Iraqi forces had worked hard to repair. In each instance, including the destructive decision by the PM, periodic failure to get the big ideas right undermined an effort that otherwise featured impressive actions on the ground.

Netanyahu can take concrete lessons from what happened in Iraq, and plan for what will happen after the present conflict, once Hamas is destroyed as a political and military force. There are many varying options — from occupying Gaza in seeming perpetuity (probably the worst option), through controlling it via proxies (that will be hard to find and empower), to evacuating it altogether and leaving a vacuum (the most dangerous), to resuscitating a two-state solution (the best long-term, but now even more politically difficult than usual). Whichever option Netanyahu, his coalition and war cabinet choose, it must be their choice alone and they must stick to it with resolution and determination. As is clear, all choices are exceedingly difficult.

Netanyahu can also look to superb leadership in contemporary events. The study of wars from the last eight decades has left us with little doubt as to why Ukraine has performed so impressively on the battlefield in its ongoing war with Russia, even as it confronts a much larger, more heavily armed adversary that routinely commits atrocities against civilians. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and his senior military commanders have demonstrated all the qualities of exceptional strategic leadership through 19 months of near-total war. In the first hours of the Russian invasion, Zelenskyy responded to American offers of refuge with the famous line, “I need ammunition, not a ride.”

Zelenskyy was articulating the big idea that would guide Ukraine’s response to Russian aggression thereafter: Ukraine would not be intimidated into submission but would fight to defend itself in what it rightly sees as its war of independence. This big idea was critical and inspiring. Zelenskyy’s personal choice to stay with his family in Kyiv, then the Russian military’s main target, mirrored yet also hardened the country’s resolve.

Zelenskyy subsequently prevented military-age Ukrainian men from leaving the country, delivered inspirational nightly updates to the Ukrainian people, and mobilized the totality of his country to repel the invaders. These decisions, together with his brilliant communications to the world, including pitch-perfect messages to the parliaments of key countries, and his energy, example and fortitude have all earned him the right to be regarded as a leader in the mold of Winston Churchill. He was, in fact, the first wartime leader since Churchill to address the U.S. Congress, something he did movingly in December of 2022.

Our research into the conduct of warfare since the mid-20th century underscores the point that strategic leadership is a key determinant in the outcome of a conflict, if not the key determinant. The ability of leaders to understand the context and nature of the conflict and to get the big ideas — the strategy — right; to communicate those big ideas throughout the breadth and depth of a unit, a country, a coalition, the world; to oversee the implementation of the big ideas, providing example, energy, inspiration, determination and solid operational direction; and to determine how the big ideas need to be refined and adjusted so that all the other tasks can be carried to conclusion — these factors have repeatedly proven necessary for victory, and they will undoubtedly remain so in the wars of the future.

Netanyahu’s challenge today is to perform those tasks in a situation and operational context that are the most diabolically difficult that one could imagine. And our big idea should be to support Israel in every way possible, which fortunately does appear to be the intent of President Joe Biden and the U.S. Congress.

----------------------------------------

By: David H. Petraeus and Andrew Roberts

Title: What the History of Modern War Offers Prime Minister Netanyahu

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2023/10/17/benjamin-netanyahu-israel-leadership-hamas-00121879

Published Date: Tue, 17 Oct 2023 05:15:40 EST