The big divide on premature death isn’t between college grads and non-grads. It’s between high school dropouts and everyone else.

For the past decade or so, Princeton economists Angus Deaton and Anne Case have been promoting a particular story about death in America. Less-educated Americans, particularly those without college degrees, have seen their life expectancy outcomes diverge from those of more-educated Americans. Much of this divide can be explained through a category that Deaton and Case call “deaths of despair”: deaths from suicide, opioid overdoses, and liver cirrhosis and other alcohol-related causes. The deaths are concentrated in non-Hispanic whites. This phenomenon indicates something is deeply wrong with the way American society treats its most marginalized citizens, including lower-class whites.

The two have been pursuing research into the death divide for the better part of a decade now; their 2020 book on the topic became a bestseller. Events over recent years — including the sharp decline in life expectancy in the US as a whole in 2020 and 2021 due to Covid-19, and before that the even more shocking first overall decline in decades in 2016 — gave the topic added urgency.

Now their work is receiving renewed attention (including a New York Times op-ed from the authors) after they presented their most recent paper last week at the Brookings Institution, centered around the following striking graphic:

Ann Case & Angus Deaton right now at BPEA: pic.twitter.com/cVCW5tVVVd

— DeLong (@delong) September 28, 2023

So what’s going on here? Is there an American underclass that’s falling behind and dying earlier than the rest of the country? Is the divide between college graduates and non-graduates increasingly central in determining life outcomes for Americans, down to the very number of years we get on this planet?

These are two different questions, and the answers seem to be, respectively, “yes” and “no.” Case and Deaton are highlighting a real problem, confirmed by other researchers: Americans with different levels of education die at different rates, and the least-educated Americans have seen their death rates surge in a way that more-educated Americans have not.

But the relevant divide does not seem to be between people who earned a bachelor’s degree — who remain a minority among American adults — and people who didn’t. Other research suggests that the problem is concentrated in specific areas of the US, and between the very least-educated Americans (particularly high school dropouts) and the rest of the country, rather than between college grads and non-grads.

Moreover, the cause of the divergence between high school dropouts and the rest of the country does not seem to be caused by “deaths of despair.” There is no doubt that the opioid epidemic in particular has wrought spectacular damage in the US. But some researchers are finding that stagnating progress against cardiovascular disease is an even bigger contributor to US life expectancy stalling out, and to mortality divides between the most- and least-educated Americans.

That implies we might want to think more specifically about heart disease, and about the American underclass, and less about the bachelor’s/non-bachelor’s divide that Case and Deaton highlight. That might enable us to produce a more useful policy agenda for tackling the problem.

Non-college grads in 1992 and non-college grads in 2021 are very different groups of people

The biggest problem to be aware of when evaluating the Case-Deaton results is that the divide they’re describing, between college grads and non-grads, has changed a lot over time. In 1992, the year they begin their analysis, 22 percent of people between the ages of 25 and 84 had a four-year college degree. In 2021, the final year they analyze, the share was 35 percent.

This rising education level suggests that there’s a large population of people — some 13 percent of adults — who wouldn’t have finished college 30 years ago, but who do now. One might reasonably expect this group to be healthier than people who wouldn’t have finished college in either period — and less healthy than people who would have finished in either period. The people still left out of college in 2021 are probably more socially and economically disadvantaged, and thus less healthy, than people who were able to attend, and people who could afford college in 1992 were relatively more advantaged, and probably healthier, than those who could.

So a group of people moving from not finishing college to finishing it should have the effect of making both college grads and non-grads, as groups, less healthy. The non-grads are losing their healthiest compatriots, and the grads are adding a somewhat less healthy group to their mix.

This means we cannot look at graphs showing a widening mortality gap between college grads and non-grads and conclude, “Something is really going wrong with less-educated Americans.” That may be true, but it may just be a statistical artifact. As Stanford economist Caroline Hoxby noted in her comments on the latest Case-Deaton paper, it’s “entirely plausible that selection accounts for most or even all of the widening mortality gap.”

Case and Deaton try to adjust for this problem. They look at how the gaps between grads and non-grads change within specific birth cohorts: among people born in 1940, say, have college grads and non-grads seen their death rates diverge more and more over time? This analysis muddies the picture considerably. For men born in 1940, for instance, the gap between grads and non-grads has shrunk over time. There’s no noticeable increase in the gap for men or women born in 1950 and 1960. Gaps do emerge over time for the cohorts born in 1970, 1980, and 1990.

What’s more, this approach doesn’t really fix the problem. To separate the world into college grads and non-grads, they check to see if people have completed a degree by age 25. But they concede that a growing share of people are getting bachelor’s degrees after 25. That means that these aren’t fixed categories, and the very same selection issues might come into play when looking at cohorts like this.

The problem is with high school dropouts, not all non-college grads

The good news is that other researchers have attempted more rigorous approaches to get around the selection problem. Economists Paul Novosad, Charlie Rafkin, and Sam Asher analyze mortality from 1992 to 2018 among the least-educated 10 percent of Americans. By definition, this group becomes no larger or smaller as a share of the population over time: it’s always 10 percent. Identifying just who this group is requires some clever statistical work, but yields some very interesting results:

This is how the trends look once you hold ranks constant. From 1992–2018, most White Americans have been doing fine mortality-wise — but the least educated 10% have faced catastrophic mortality increases. 9/N pic.twitter.com/3ZpybrYyYj

— Paul Novosad (@paulnovosad) December 16, 2022

Among both Black and white middle-aged Americans, death rates were falling among the most-educated groups pre-Covid. For those in the middle of the education spectrum, death rates have been falling for Black Americans and stagnant for whites; Black death rates still exceed those for whites but the gap is narrowing. For the least-educated, which roughly means high school dropouts, death rates have been rising starkly for white men and women, and rising slightly for Black women, while staying roughly constant for Black men. (Novosad, Rafkin, and Asher also look at death rates in other age ranges, but note that death is rare enough before you get to your 50s that it doesn’t affect life expectancies in the US as much.)

Case and Deaton in their latest piece describe this as confirmation that the “qualitative” takeaway from their research is correct. I’m not sure I’d be that generous. “White high school dropouts are dying at higher and higher rates” implies that a small but significant share of the population is experiencing a mortality crisis. “Americans without a college degree are dying at higher and higher rates” implies that the majority of Americans are experiencing a crisis, since a majority of Americans don’t possess a college degree even today. That might be a better narrative for convincing people to care about the most vulnerable, but it doesn’t give us as much information about where the problem is.

The problem is highly geographically concentrated

At this point you may be wondering: If we’re concerned about how lower-socioeconomic-status Americans are doing in terms of mortality, why are we dividing them by education? Why not compare rich versus poor Americans, normally identified based on income?

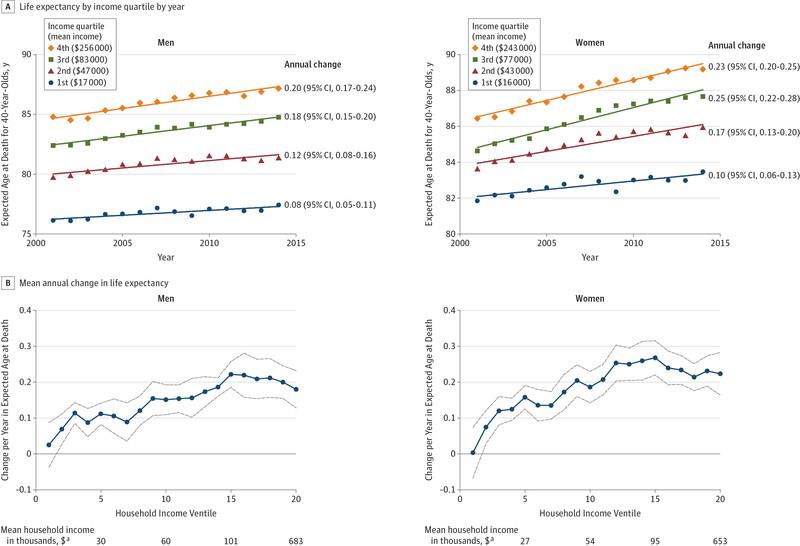

In 2016, economists Raj Chetty and others used US income tax data and death certificates to track how mortality varied based on income and how the relationship changed between 2001 and 2014. That isn’t a terribly long period across which to compare, but Chetty and colleagues confirmed that more income is associated with lower death rates and that the gap got worse over the period studied.

Chetty et al 2016

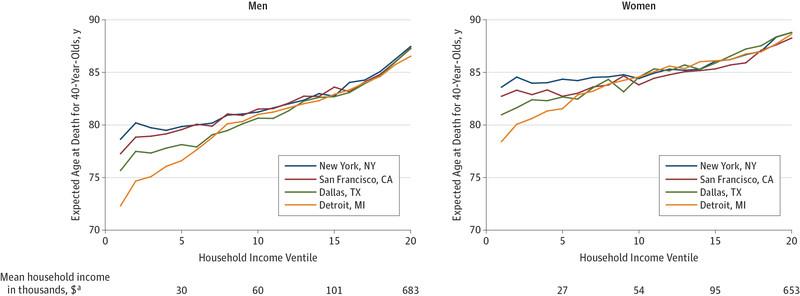

But they also found that the gap varies substantially based on geography. While it’s true that rich people in America live significantly longer than poor people, that’s much less true in New York City. It’s not true in California as a whole. Heavily urban areas with high education levels see a modest relationship between income and death rates. More-rural, less-educated areas, by contrast, see a very strong relationship between the two.

Chetty et al 2016

Areas with smaller mortality gaps tend to be places, the researchers find, with lower rates of smoking and higher rates of exercise, which makes sense when you consider that the variation in death rates between cities is driven not by factors like car crashes or suicide but conditions like heart disease and cancer, which are themselves driven in part by lifestyle conditions. Local unemployment rates and other indicators of the health of the local labor market did not seem to be associated with longevity, nor did income inequality. These aren’t firmly causal findings, to be clear, but they might be suggestive of potential causes to investigate.

This work doesn’t debunk the Case-Deaton research, but it does highlight ways in which that research is somewhat incomplete. Case and Deaton do not break down their findings by state or city to see if the relationship they find is only showing up in certain places. Together with the Novosad research, this data suggests that if we want to tackle rising mortality among some Americans, we need to be thinking specifically about problems with the very poorest high-school dropouts in certain areas of the country, rather than about some kind of broader — and therefore harder to address — national malaise.

What’s causing these early deaths?

One of the more useful contributions of the latest Case-Deaton paper is its decision to zoom out from focusing on “deaths of despair” to include other contributions to rising mortality in the US, in particular cardiovascular disease.

There’s little doubt that the ongoing opioid crisis has contributed to surging deaths, particularly among more vulnerable Americans, with smaller roles attributable to non-drug suicides and alcohol. One recent paper found that increasing drug use from 1999 to 2016 reduced the life expectancy of American men by 1.4 years, and that of women by 0.7. In West Virginia, the most affected state, the reductions were 3.6 and 1.9 years respectively. In 2020 and 2021, Covid was the dominant force reducing life expectancy, with the effects very different based on class: People with disproportionately high-paying laptop jobs who were able to work from home were less exposed and so died less.

But the overall life expectancy problem in the US also has far more to do than we often recognize with stagnating progress against cardiovascular disease, which is still the leading cause of death in the US. Researchers Neil Mehta, Leah Abrams, and Mikko Myrskylä argued in a 2020 paper that the dominant reason life expectancy has stalled in the US is not that drug deaths have grown but that a previously large, robust decline in deaths from cardiovascular disease has stalled out. The death rate fell by half between 1970 and 2002, but given that it’s still common enough to cause 695,000 deaths in 2021, a stalled decline could be a very big deal.

Though explanations for this stagnation are still unclear, the authors present a couple of options: rising levels of obesity (especially at younger ages, compounding negative health effects over more time), or, counterintuitively, the US’s early success at discouraging smoking (which could explain why its cardiovascular death rates aren’t falling as fast as those in Europe, which gave up smoking later on). They find that the stagnation from cardiovascular disease is broad-based geographically in the US, unlike the rising death rates among low-income Americans studied by Chetty et al.

Economists Novosad, Rafkin, and Asher make similar points in their paper on the fate of the least-educated Americans over time. As of their data endpoint in 2018, “deaths of despair” — that is, from drug overdoses, suicides, and alcoholism — “account for a large share of mortality increases for young whites, but a very small share of rising mortality among older whites and very little of the divergent mortality rates of black,” they note. “Further, deaths of despair have increased more uniformly across the education distribution than deaths from other causes.” In other words, while the overall rise in mortality is concentrated among the least-educated, the opioid, suicide, and alcohol-related rise is not.

The middle-aged whites without high school diplomas Novosad and colleagues study have, however, seen their death rates from cancer, heart disease, and respiratory disease increase, while more-educated Americans have seen death rates from these diseases fall. A new investigation from the Washington Post similarly concludes that chronic conditions like heart disease and cancer are driving more of the life expectancy divide between rich and poor counties than factors like opioid overdoses or homicides.

All this points to a very specific challenge that policymakers must confront: How to reduce deaths from cardiovascular disease (and also cancer) among the poorest, least-educated Americans. Case and Deaton like to prescribe various economic measures as ways to combat rising death rates, like eliminating the link between employers and health insurance, expanding affordable housing, strengthening unions, and removing needless requirements that certain workers have bachelor’s degrees.

I happen to think all those policies are good ideas. But I’m somewhat skeptical they would move the needle on heart disease among high school dropouts, especially compared to more targeted approaches like expanding cholesterol screening or ensuring Medicaid covers medicines like semaglutide that reduce the risk of heart disease.

People dying now cannot wait for the whole US economy to transform to be more worker-friendly, as nice as that might be. They need solutions that are tailored for their specific problems, that can be implemented soon.

----------------------------------------

By: Dylan Matthews

Title: What a striking new study of death in America misses

Sourced From: www.vox.com/future-perfect/23895909/angus-deaton-anne-case-life-expectancy-united-states-college-graduates-inequality-heart-disease

Published Date: Wed, 04 Oct 2023 12:00:00 +0000