American businesses seeking to operate overseas typically face few barriers from the U.S. government. But when it comes to China, a bipartisan group of lawmakers — and the White House — want to change that.

Congress is considering legislation allowing the government to screen American investments in China and other adversarial nations — and potentially deny them if a project threatens national security. At the same time, the White House is talking about issuing executive orders to increase scrutiny of American funding for Chinese startups and technology firms, expanding a ban that today only exists for a select group of firms aligned with the Chinese military.

Taken together, the actions would represent an unprecedented expansion of government oversight sure to chill some American investment in the Chinese economy and escalate commercial tensions with Beijing. But supporters say they are necessary to stop American banks from funding China’s technological development and prevent U.S. supply chains from being reliant on Beijing for goods used in critical industries, like medicine, energy and defense.

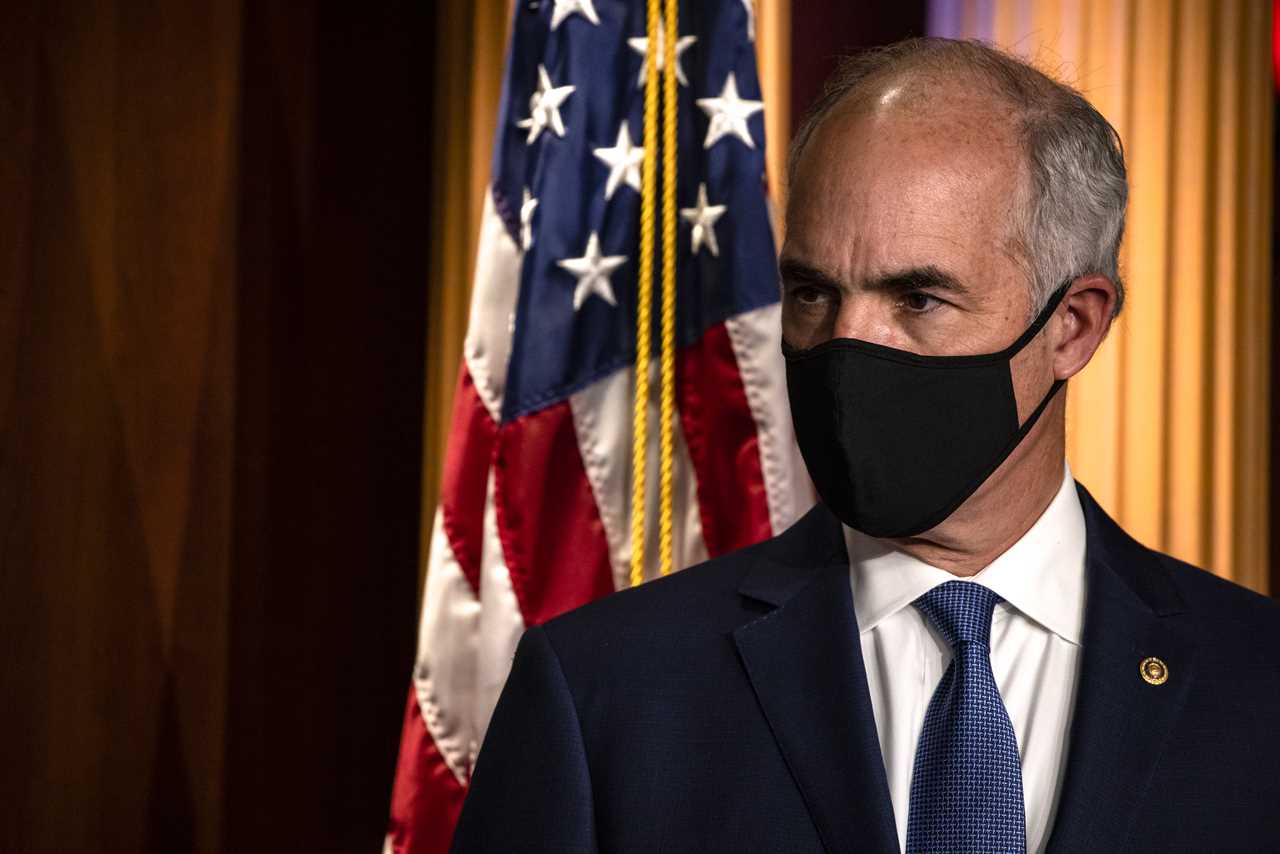

“We’re in an economic war, whether we want to use that language [or not],” said Sen. Bob Casey (D-Pa.), who is leading a bill with Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas) that would expand oversight of U.S. supply chains in China. “I think it requires that we examine some issues that maybe 10 or 15 years ago we didn’t have to worry about.”

That bill, currently under consideration as part of Congress’s anti-China economic legislation, has already been delayed multiple times by corporate objections to the expansion of government oversight. But some House Democrats are now behind the plan, potentially giving it new momentum. Those legislative efforts and the White House discussions about executive orders have many policymakers and corporate leaders convinced that expanded oversight is inevitable, sooner or later.

“I think it's a fait accompli,” Jeffrey Fiedler, a member of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, which called for enhanced supply chain oversight in its 2021 report to Congress, said during a recent Atlantic Council panel discussion.

“The question,” he added, “is how extensive” the oversight will be.

Opponents say the government already has the tools it needs to address security concerns related to outbound investments.

“Congress and the administration should focus on effective implementation” of existing export controls “before passing another,” said John Murphy, senior vice president at the Chamber of Commerce, which has lobbied against Casey and Cornyn’s supply chain bill for over a year.

The effort to screen American investments in China started before the pandemic. Lawmakers proposed expanding supply chain oversight in 2018 but ultimately dropped the effort.

The Trump administration made some moves on its own, issuing an executive order in 2020 to ban American investments in more than 30 military-linked Chinese firms. It also moved to delist Chinese companies from American stock exchanges if they didn't comply with disclosure requirements, acting on new authority Congress passed in 2020.

Biden revised and expanded Trump’s list of blocked military companies with an executive order last June. But the oversight remains relatively narrow, involving 60-70 Chinese firms, a senior administration official said.

That has the White House and congressional China hawks considering broader policies, like Casey and Cornyn's bill to set up a federal commission to screen investments in China that could affect critical industries like healthcare, energy and defense.

The duo tried to attach the legislation to the Senate’s broad anti-China legislation last summer, and to the annual defense spending bill late in fall. But they were rebuffed each time by corporate interests and aligned lawmakers, who said the bill was too broad and questioned whether the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, which is supposed to head the commission, had the resources to carry out the reviews.

The outbound investment provisions “represent a new, expansive policy idea that could have significant, negative ramifications far exceeding national security,” said Sen. Pat Toomey (R-Pa.), the lead Republican on the Senate Banking Committee, who helped keep the language out of Senate legislation last year. “Given this broad impact, the Senate should thoroughly vet this idea and get input on its impact on our national security, consumers, and affected stakeholders prior to it being inserted into any larger package.”

But now, House Democrats have taken up the mantle, with Reps. Rosa DeLauro (Conn.) and Bill Pascrell (N.J.) attaching the outbound investment bill to their version of anti-China legislation set to go to a conference committee with the Senate in the coming weeks. The Senate sponsors are hopeful that lawmakers can agree to keep the provision in the final bill, even as the upper chamber balks at the rest of the House’s version, which is stuffed with other Democratic priorities.

The supply chain screening provision “is about the only good part” of the House bill, Cornyn said in a brief Capitol Hill interview. “We've obviously tried to get some traction before, and we've been unable to do it, but I can't think of a better vehicle to do that than a bill that's focused on China competition.”

Though the White House has not endorsed the bill itself, the Senate duo says the Biden administration has been supportive of the idea of outbound investment screening.

“We’ve had some good dialogue with members of the administration,” including Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, Deputy Treasury Secretary Wally Adeyemo and others, Casey said. “So we're going to continue that as we move to the next phase.”

At the same time, the Biden administration is discussing whether to act on its own to expand the government’s oversight of American supply chains in China and American banks and funds that invest in or lend to Chinese firms. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan said last summer that the administration was considering ways to crack down on companies that "circumvent" export rules or help fund China's "technological capacity" — discussions the White House says are still ongoing.

“As part of our competition with China, we want to make sure that we have an appropriate set of tools in place in order to help maintain our technological and competitive edge,” the senior administration official said. “We have export controls, particularly around a range of high-tech technologies and companies. We also have a set of investment restrictions. But the current set of investment restrictions is fairly narrow.”

The official declined to detail exactly which steps the White House is considering, but trade veterans who have worked on the issue say that the actions fall into two broad categories. One is to increase scrutiny of U.S. companies that have supply chains that run through China, as the Casey-Cornyn bill aims to do. The second, considered by the Trump administration in 2018 and 2019, would be to expand oversight of American financial institutions that fund or do business with Chinese firms, especially in cutting-edge technology.

Screening American funding for Chinese companies may be an “easier sell politically,” said Clete Willems, a partner at Akin Gump who served on the National Security Council and National Economic Council during the Trump administration’s debates on the issue.

“Funding Chinese innovation is one thing. Telling U.S. companies that they can't place supply chains in certain countries is another,” he said. “I think it would be better to focus on funding that promotes Chinese innovation in sensitive technologies, rather than unprecedented supply chain management, which could undermine overall U.S. economic competitiveness.”

The senior administration official said that discussions on a potential executive order are ongoing, but the timing of any action remains unclear. The Treasury and Commerce Departments, which would likely have leading roles in any financing restrictions, declined to comment.

Whether the White House takes action with Congress or on its own, it can expect backlash from corporate America. The Chamber and other business groups argue that the Casey-Cornyn legislation is too broad and would stifle most American business in China. A January report from the Rhodium Group, a consultancy, estimated that 43 percent of American investments would be covered by the bill.

Both senators have signaled they are open to negotiations in Congress and with the White House on the details of the legislation. But they reject the corporate warnings that most or all new American business in China could dry up.

“Sounds like a Chicken Little argument to me,” Cornyn said. “My request to them would be to sit down and talk to us and tell us what your concerns are, and maybe we can find some common ground. But don’t just tell us, ‘No way.’ I think it’s a real problem, and it needs to be addressed.”

----------------------------------------

By: Gavin Bade

Title: ‘We’re in an economic war:’ White House, Congress weigh new oversight of U.S. investments in China

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/2022/02/19/china-investments-economy-us-congress-00008745

Published Date: Sat, 19 Feb 2022 07:00:00 EST