For six weeks, while Sen. John Fetterman received treatment for clinical depression at Walter Reed Medical Center, handwritten cards poured into his Washington office. His staff fielded phone calls from constituents passing along well wishes. Others called simply to thank him for being upfront about his condition.

When one of Fetterman’s senior aides checked into a hotel in Pittsburgh recently, a middle-aged woman saw their Senate ID and asked for whom they worked. When the aide told her, the woman responded: “He’s so brave.”

The reaction has been, overall, a shocking and pleasant surprise to Fetterman’s team, which worried about their boss and felt anxious about how the public would respond to revelations that he has depression.

What they and others have discovered is that the country is increasingly open about it. And that the politics are changing around it.

Sen. Tina Smith (D-Minn.) penned a personal essay about Fetterman and how the news of his depression dredged up old feelings about her own fight with the disease in her teens, and again as a young mom. Republican Sen. Katie Britt’s team sent cookies and brownies to Fetterman’s office almost once a week, the senior Fetterman aide told POLITICO. And before President Joe Biden kicked off his budget speech in Philadelphia last month, he spoke directly to the senator: “John, if you can hear this at all, we’re with you, pal. We’re with you,” he said, drawing cheers from the crowd.

“It was like, damn, this is cool. You never know how it’s going to go, you know? There’s no playbook for what John did,” said the Fetterman aide. “But if you can learn anything from John Fetterman, it’s that it’s OK. Things can get better. It is OK to get help. That’s what he wants people to take away from this.”

Fetterman’s return to the Hill on Monday will provide the most visible example of the nation’s capital — a city where public figures often fight to keep personal battles shrouded in secrecy — slowly embracing an issue that affects 1 in 5 Americans in a given year. From Congress to the White House, policymakers have begun leaning into mental health as a key policy priority.

“In the ’50s and ’60s, nobody said the word cancer. We talk about cancer now. We need to get to that point where we talk about depression. We talk about bipolar disorder. We talk about PTSD. We talk about schizophrenia, and acknowledge that these are illnesses for which there is treatment, and people can have satisfying, fulfilling lives,” said Lynn Bufka, associate chief of practice transformation at the American Psychological Association and a licensed psychologist in Maryland.

“So anytime we have more visible figures talking about the reality, it helps people to see ‘Oh, that person is a lot like me.’”

Not only are politicians opening up about their private struggles and decisions to seek treatment but they are doing it while staying in office, said Jason Kander, the former secretary of state of Missouri. Kander, a rising star in the Democratic party, ran for Kansas City mayor in the 2019 election. He dropped out after revealing he had post-traumatic stress disorder and depression after his service in Afghanistan.

“I announced that I was leaving public life for a while to go get help … now I’m a public person again, and I’m trying to be that role model as best I can. But there’s a difference between that next level of what John Fetterman is doing,” Kander said in an interview. “I’m aware of the social media comments that are like, ‘Oh, whatever happened to that guy after he made that announcement?’ And that’s fine, but it’s really great that in the case of John Fetterman, or Ruben Gallego, people see, ‘Oh, they made this announcement, and their pursuit continued.’”

The shift in Washington can be attributed to a number of factors, Bufka said. After decades of advocacy work from the APA and other organizations focused on mental health education, the media now talks about mental health more. The Covid pandemic also greatly exacerbated the crisis, forcing politicians to face the issue head on as one impacting their constituents — and their own lives.

Biden followed a similar path. He had spoken in the past about mental health and worked on the issue as vice president, announcing Obama White House efforts to increase access to mental health services. But during the 2020 campaign, the issue became personalized as he faced questions about his son Hunter’s struggles with mental health and addiction.

“The idea that we treat mental health and physical health as though somehow they’re distinct — it’s health,” Biden said during the interview with CNN. “... I’m confident, confident, he’s going to make it.”

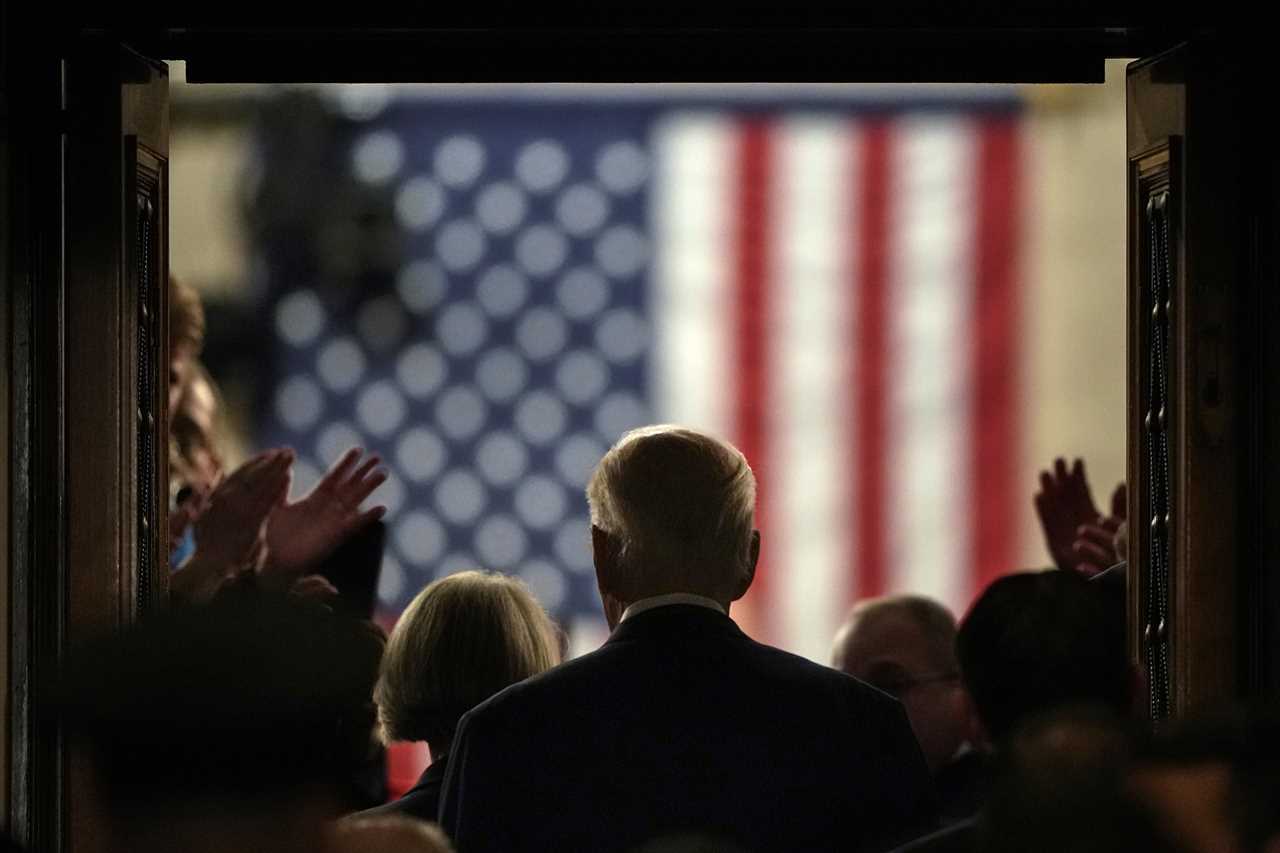

The focus continued into his presidency. During his first State of the Union address, Biden talked about how the pandemic impacted kids, increasing social isolation, anxiety and learning loss. As part of his “unity agenda,” he outlined the White House’s strategy for combating the mental health crisis: creating healthy learning environments, strengthening system capacity and connecting more Americans to care.

The American Rescue Plan included funding to expand Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics, invest in the 988 suicide prevention hotline and launch projects to tackle the impacts of social media and kids. Biden’s latest budget requests $139 million for research and another $16.6 billion to increase mental health care programs in the Veterans Affairs Medical Care program.

“Having the White House be public about this is is meaningful. And I suspect — I would never deign to speak for the president — but I suspect that the contemporary veterans in his family have helped him understand this,” said Rep. Seth Moulton (D-Mass.), who has spoken about his PTSD after serving in the military.

There has been no shortage of administration officials talking about the growing crisis, including Domestic Policy Council Adviser Susan Rice, and Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, who has said in interviews that he accepted Biden’s offer to serve a second term because of the dire state of the country’s emotional health.

During White House events, Murthy has talked about about his own struggles with mental health as a young boy and about his uncle, who died by suicide after a silent battle with depression.

Still, the steps forward don’t negate the reality that a stigma still exists, Smith said. She suspected that if one were to do the math, there were likely dozens of members of Congress choosing to not talk about their mental health, fearful of what it could mean for their political careers.

Even as Fetterman’s openness has been met with a positive response, stories like the one of Tom Eagleton, the Democratic running mate for presidential nominee George McGovern who withdrew from the ticket after acknowledging was treated for clinical depression and received electroshock therapy, still haunt politicians.

Then there was former Rep. Patrick Kennedy who left politics to focus on his addiction and bipolar disorder. He entered a rehabilitation center after crashing his car into a barricade on Capitol Hill in 2006. In a 2016 interview, Kennedy noted that there were moments he knew he needed help, well before that breaking point. But back then, politicians didn’t talk about these things.

“It is getting better, but individuals still take risks when they speak out … people are still willing to jump to the conclusion that because you have a mental health issue, that means are you really capable of serving? Can you really do what you need to do?” Smith said.

“But to me, it’s worth it. The positive side of it is the people out there, especially the young people, who see folks like me — who by all appearances have my act together — being open about it. That creates a door for them to walk through.”

----------------------------------------

By: Myah Ward

Title: Washington used to abhor talking about mental health. No more.

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/2023/04/17/mental-health-fetterman-senate-00092233

Published Date: Mon, 17 Apr 2023 03:30:00 EST

Did you miss our previous article...

https://consumernewsnetwork.com/politics-us/the-worst-case-scenario-for-drought-along-the-colorado-river