David France moved to the Big Apple to be a gay rights activist in the summer of 1981, just before a New York Times headline warned of a “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals,” which turned out to be AIDS.

The disease soon affected France’s coworker, who said goodbye to him on a Friday and was dead the following Wednesday.

France and others who lived through the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s and 90s feel a similar sense of doom toward the current monkeypox outbreak — and what they see as the U.S. government’s botched response to a disease that again has disproportionally affected gay men.

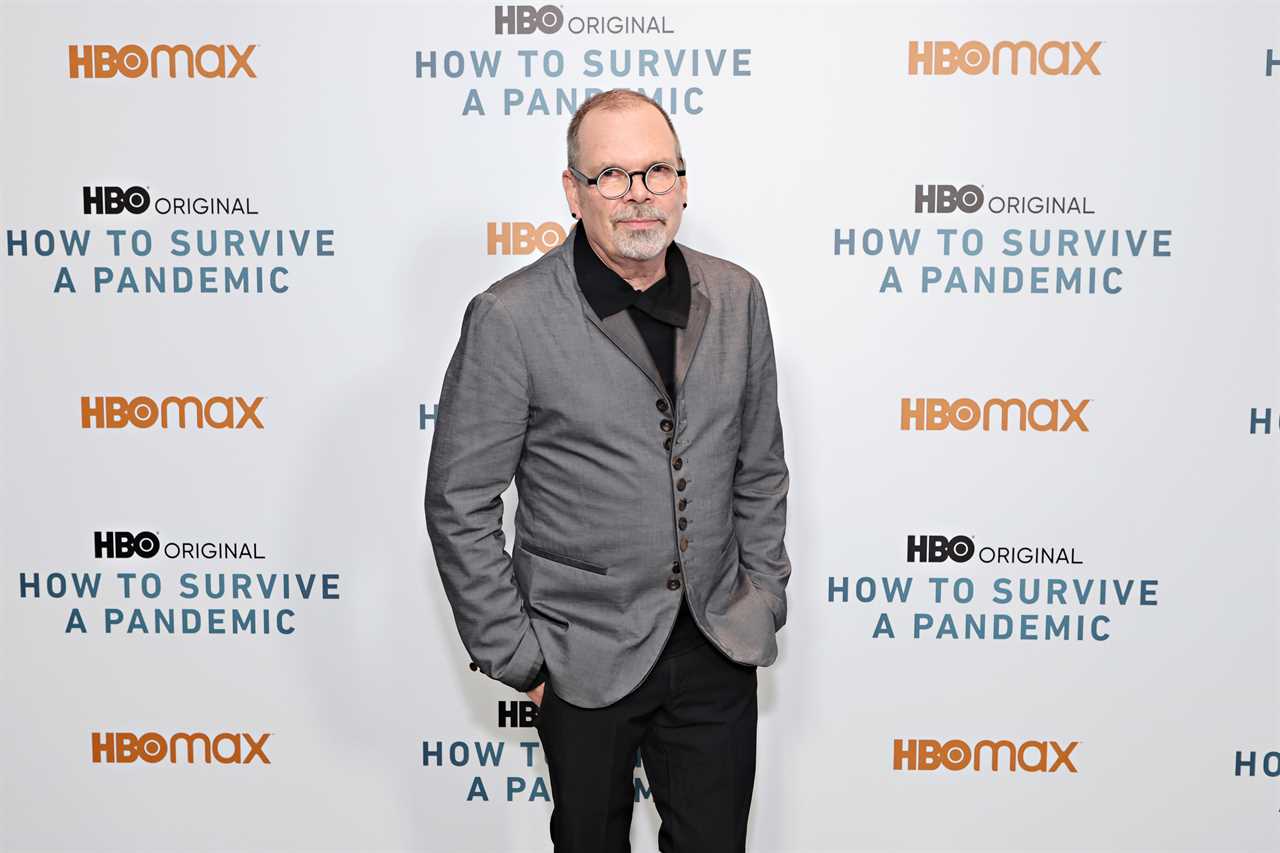

A “reason people are feeling the parallels so acutely now is because of the rise in anti-LGBTQ sentiment, which preceded HIV, also,” said France, now a filmmaker whose work includes “How to Survive a Plague,” an Oscar-nominated documentary on the AIDS response.

He and other advocates have increasingly criticized the Biden administration, and the health community worldwide, for moving too slowly on monkeypox testing and vaccines, and failing to clearly communicate the risks of the disease to the community it has overwhelmingly affected: men who have sex with men. This year’s first confirmed U.S. case of monkeypox was recorded on May 18; there are now more than 6,320 nationwide — a number expected to rise significantly.

“I'm angry beyond belief that we've let it spread this far, and that the federal government couldn't get its act together to figure out how to ramp up testing rapidly, to figure out how to do active surveillance to make sure that vaccines and treatments were here when they needed to be,” said Gregg Gonsalves, a global health activist and an epidemiologist at Yale University.

The administration seems to finally be hearing these concerns. On Tuesday, in a move to improve the response and blunt criticism, President Joe Biden named leading officials at the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to head the national monkeypox response.

Robert Fenton, a longtime FEMA official, won the White House’s trust during the Covid vaccine rollout for his help in standing up the administration’s network of Covid vaccine sites. He’s expected to manage the logistics at the center of the response, including efforts to speed distribution of tests and vaccines. Demetre Daskalakis, who will be Fenton’s deputy, helped lead the CDC’s work on HIV/AIDS and is well-known for his work engaging the LGBTQ community on public health issues — expertise that is likely to guide the administration’s bid to slow transmission in the hardest-hit areas.

The question is whether such moves came too late.

Until recent weeks, the White House had largely left it to the health department to direct the monkeypox response. But the department’s leadership has struggled to coordinate the sprawling effort, leading to vaccine and testing shortages and intense criticism from activists and health experts. The response continues to be hampered by difficulties collecting data from individual states, allowing cases to spread throughout the nation largely unseen.

Gonsalves noted that there was a lack of a proactive and cogent response from governments across the world, which he said should have been better prepared after AIDS and especially the Covid-19 pandemic. The U.S. government in particular, he argued, was again caught flat-footed. He blamed “our shitty public health and pandemic preparedness in general, but the sort of wishful thinking out of the White House is just astounding.”

While monkeypox, unlike AIDS, has a vaccine, the disease is spreading rapidly enough to compel people who lived through that past crisis to see parallels to this one. Chief among them, a growing sense among activists that, decades later, public health officials are making missteps that could again leave LGBTQ people feeling like an afterthought.

“This time, they had the tools, right?” France said. “They had the vaccines and they had a connection with the community, which they could message about prevention.”

But there are obvious shortcomings in the parallel too, as Biden administration officials are quick to note. And it’s not just because no one in the United States is known to have died from monkeypox. The disposition of the White House towards the affected community is wildly different, too.

The Biden administration is taking the current outbreak seriously, said Harold Phillips, director of the Office of National AIDS Policy in the White House. He noted during the Reagan administration, the press secretary joked about AIDS with reporters during press briefings.

“There are some similarities between the community that is being impacted by this disease. The pain, suffering, the fear of stigma, but this was not a laughing matter this time in the White House,” Phillips said.

After the first confirmed U.S. case of monkeypox was identified in May, the Biden administration ordered 36,000 doses of vaccines within two days and 300,000 doses within the next month, White House aides said. Despite the initial shipments, shortages have persisted, especially in the hardest hit cities. Within the past week, states of emergency were declared in California, Illinois and New York over the spread of the disease.

“Public health in our country both is underfunded and also fragmented,” Phillips said, noting the current outbreak comes amid an ongoing pandemic and the emergence of increasingly virulent Covid variants.

“We all said during Covid we need to be ready and prepared for the next one. And I don't think we expected this to come as soon as it did or as quickly as it did,” he said.

The move to add federal coordinators to lead the response has been met with cautious optimism by some advocates. But even health officials and experts concede there’s little at this point they can do to halt the spread of monkeypox until more vaccines come available. The U.S. is expected to have just 2 million shots of a two-dose vaccine by the end of the year, resulting in predictions of prolonged shortages.

The monkeypox outbreak in the meantime has grown exponentially, with case counts doubling each week. If transmission isn't slowed soon, health experts worry, the country will lose any hope of containing the disease, allowing it to become entrenched as an indefinite threat.

France said increasing vaccines alone won’t be effective unless the administration also better coordinates its messaging to the community being affected. There may be more widely available treatments and more empathy for the afflicted than existed during the AIDS epidemic. But without constructive communication, it wouldn’t work as planned.

“Those of us like me who came up in the plague years of HIV, 15 years before there was any effective treatment, we learned how to put ourselves in ways that were safe and effective,” France said. “Here's the message. Here's the solution. Bring them both out at once. Then everybody knows what they need to do and they do it. And right now, that message isn't there. Nobody knows where those vaccines are, if they're even going to come, if the second dose is going to come. There's, there's nobody.”

----------------------------------------

By: Eugene Daniels and Adam Cancryn

Title: U.S. monkeypox response stirs up anxious memories of AIDS era for activists

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/2022/08/04/monkeypox-response-aids-era-parallels-00049663

Published Date: Thu, 04 Aug 2022 03:30:00 EST