A video on Facebook claiming that Washington police unlawfully attacked Jan. 6 protesters racks up nearly 140,000 views. Across YouTube and Twitter, users post thousands of comments claiming Joe Biden’s presidency is a fraud. Within fringe social networks, extremists openly discuss violent attacks on Pennsylvania and Arizona election officials who approved the 2020 vote count.

A year after supporters of former President Donald Trump staged a deadly assault on the Capitol, the social media platforms where people organized and celebrated the riot are still ablaze with the same rumors, threats and election misinformation that flourished online before last year's violence.

The ongoing flood of extremist content, based on POLITICO’s review of thousands of social media messages across six separate networks, comes despite efforts by major platforms such as Facebook, Google and Twitter to turn down the temperature — including by removing Trump himself. Meanwhile, Congress remains gridlocked on even modest steps to toughen oversight of social media companies, such as forcing them to share data with the researchers and outside groups that track the spread of misinformation.

Google, Twitter and Facebook's parent company, Meta, say they have taken unprecedented steps to remove inciting content, deleting scores of posts and tens of thousands of accounts that questioned the outcome of the 2020 election and the causes of the Jan. 6 insurrection.

Yet despite these efforts — many of which have drawn accusations from conservatives of unduly harming free speech — the online world has become even more polarized, violent and politicized since rioters stormed the Capitol in January 2021, according to policymakers, law enforcement and misinformation experts. That situation could prove to be a tinderbox once campaigning begins to heat up for November’s midterm elections.

“I think social media played a role in both isolating Americans from each other, and in accelerating extremist views about our politics and spreading baseless conspiracy theories,” said Sen. Chris Coons (D-Del.), who is leading one of the only bipartisan efforts to boost greater outside access to social media platforms’ data.

Congress has few tools for addressing online misinformation directly, especially given the First Amendment's broad free-speech protections. Instead, that policing role has largely fallen to the social media companies — which, as federal courts have repeatedly pointed out, have the right to outlaw falsehoods, hate and extremism on their platforms.

But a year on from the Jan. 6 riots, many of these social media companies have struggled to address the issue. They’ve hesitated to become the final judge on where to draw the line between constitutionally protected — but often problematic — speech and harmful misinformation for their hundreds of millions of daily users.

In private Facebook groups with thousands of members, swing state voters routinely post debunked news articles alleging widespread election fraud by the so-called deep state, and question whether November’s vote could repeat those activities.

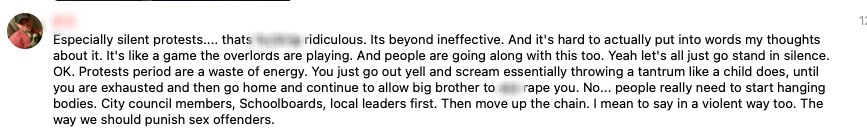

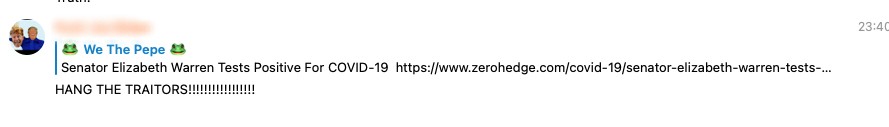

On YouTube, videos claiming that Trump’s opponents used Covid-19 as a biological weapon to steal the election still rack up tens of thousands of views. (After POLITICO flagged one video making those allegations, which had garnered more than 411,000 views, YouTube removed it because it violated the company's election integrity policy.) And on Gettr, a right-wing social network popular with many Trump supporters, some users continue to call for the hanging of elected officials they accuse of undermining the country’s democratic traditions.

Across all six social networks POLITICO examined — Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Gab, Gettr and Telegram — conspiracy theorists frequently associated the outcome of the 2020 election with the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. That includes unfounded allegations that the federal government was limiting people’s freedoms to favor Biden's political agenda.

In response, Facebook, Google and Twitter said they had removed, collectively, hundreds of thousands of accounts, pages and channels that spread election misinformation, including banning extremist movements and conspiracy theories such as QAnon from their platforms. They also had tweaked their algorithms to promote mainstream news about the 2020 election and Jan. 6 riots, and invested heavily in content moderation and fact-checking partnerships.

Twitter said that both before and after Jan. 6, the platform has taken “strong enforcement actions” against accounts that incite violence or could lead to offline harm. YouTube said it is being "vigilant" ahead of this year's midterms to respond to election misinformation. Facebook said it was in contact with law enforcement that handled domestic terrorism threats.

In contrast, Gettr and Gab promote the wide berth they give users to express themselves without fear of censorship, unlike the mainstream platforms, and say they have seen a significant increase in users during the past 12 months. Telegram did not respond to requests for comment.

Lawmakers, meanwhile, are barreling toward the midterms with sharply contrasting political narratives about last year’s violence: Democrats want online companies to do more to stamp out election-related misinformation, while Republicans allege these platforms are seizing on the riot to censor right-wing voices.

"One of the most alarming developments of 2021 since the insurrection has been an effort, especially among influencers and politicians, to normalize conspiracy theories around election denial," said Mary McCord, a former national security official and executive director of Georgetown University's Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection.

"They've mainstreamed ideologically driven violence," she added. "An alarming number of Americans now believe that violence may be necessary to 'save the country.'"

A political hot potato

One major reason policymakers and social media companies still struggle to contain Jan. 6 falsehoods is that the Capitol assault itself has become contested territory.

In the days following the riots, both Republicans and Democrats condemned the deadly violence, with longstanding Trump allies such as Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) calling for an end to hostilities. Trump himself faced revulsion from many of his supporters and even some of his own appointees immediately after Jan. 6.

That initial bipartisanship gave the social media giants political cover to remove reams of election misinformation and hand over data to law enforcement agencies investigating the attack. The bans of Trump — though Google’s YouTube platform and Facebook reserved the right to reinstate him before the 2024 presidential election — also marked a watershed moment.

"Trump being deplatformed was when the companies crossed a line into a new type of enforcement," said Katie Harbath, a former senior Facebook public policy executive who previously worked for the Senate Republicans' national campaign arm. "After that, they've felt more comfortable about taking down content posted by politicians."

That comfort did not last long.

Instead, GOP voters and politicians have increasingly embraced the falsehoods about the 2020 election that helped stoke the attack, while Congress — and many in the country — is split along party lines about what really happened on Jan. 6. That has left social media companies vulnerable to partisan attacks for any action they take or fail to take linked to last year's riots.

To Democrats, the companies simply haven’t done enough.

“It’s clear that some social media companies have chosen profits over people’s safety,” said Rep. Frank Pallone (D-N.J.), chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, which has brought the CEOs of Facebook, Twitter and Google to testify about their role leading up to the Jan. 6 insurrection. “These corporations have no intention of making their platforms safer, and instead have taken actions to amplify content that endangers our communities and incites violence.”

Republicans, though, have increasingly recast the rioters as freedom fighters raising valid questions about the outcome of the election. Lawmakers including Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) have portrayed the Democratic-led investigation into the insurrection as a “political witch hunt on Republicans and Trump supporters.” (Greene, who made that accusation in a Facebook video that has received 309,000 views since early December, had her personal Twitter account permanently suspended this week for posting Covid misinformation.)

They’re also rallying around the people who have been kicked off of social media.

House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy has threatened reprisals against the liability protections that online companies enjoy under a law known as Section 230 — which shields companies from lawsuits for most user-posted content and allows them to moderate or remove material they find objectionable.

McCarthy warned in a series of tweets on Tuesday, after Greene’s suspension, that a future Republican House majority would work to ensure that if Twitter and other social media companies remove “constitutionally protected speech (not lewd and obscene),” they will “lose 230 protection.”

“Acting as publisher and censorship regime should mean shutting down the business model you rely on today, and I will work to make that happen,” he added.

To Democrats, the platforms' failure to stop all Jan. 6 hate speech from circulating online highlights the need for new laws. They hoped to gain momentum from last fall’s disclosures by Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen, who released internal documents showing the tech giant had struggled to contain insurrectionists' posts in the run-up to Jan. 6.

A Democratic-led bill introduced after Haugen’s Senate appearance seeks to remove online platforms’ Section 230 protections if they “knowingly or recklessly" use algorithms to recommend content that can lead to severe offline emotional or physical harm. The bill has no Republican backing and has drawn criticism for potentially infringing on free speech.

In multiple briefings, lawmakers and staffers of both parties confronted the large social media companies with accusations that they had played a role in attacks, according to two tech executives who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss closed-door meetings. The discussions have often turned personal, with policymakers accusing the companies of playing fast and loose with American democracy.

With little bipartisan agreement, one of the tech executives added, the social networks are increasingly cautious in how they handle Jan. 6-related content that does not categorically violate their terms of service.

“Congress has struggled to find an appropriate path forward,” Coons conceded when asked about lawmakers’ role in handling Jan. 6 and election misinformation. “We have different views of what's the harm that most needs to be stopped based on our politics and because — as a society — we're committed to free speech.”

The misinformation rabbit hole

Since the Capitol Hill riots, the major social networks have removed countless accounts associated with white supremacists and domestic extremists. They've tweaked algorithms to hide Jan. 6 conspiracy videos from popping into people's feeds. The companies have championed investments in fact-checking partnerships and election-related online information centers.

Yet scratch the surface, and it is still relatively easy to find widely shared posts denying the election results, politicians promoting Jan. 6 falsehoods to millions of followers and, in the murkier parts of the internet, coordinated campaigns to stoke distrust about Biden's 2020 victory and to coordinate potential violent responses.

POLITICO discovered reams of posts related to 2020 election and Jan. 6 misinformation, across six separate social media networks, over a four-week period ending on Jan. 4, 2022. The findings were based on data collected via CrowdTangle, a social media analytics tool owned by Facebook that reviews posts on the platform and on Twitter, as well as separate analyses via YouTube and three fringe social networks, Gettr, Telegram and Gab.

The content included partisan attacks from elected officials and online influencers peddling mistruths about Jan. 6 to large online audiences. Within niche online communities on alternative social networks, domestic extremists shared violent imagery and openly discussed attacking election officials.

"You don't have to look far, and everything is still the same as it was before Jan. 6," said Wendy Via, co-founder of the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism, a nonprofit that tracks these groups online. "Not nearly enough has been done."

On Facebook, private groups of swing-state voters in Wisconsin and Florida repeatedly shared debunked claims from right-wing news outlets alleging that election officials committed fraud to sway the 2020 election in favor of Biden. Almost none of these posts ran with disclaimers that such claims were false.

On YouTube, a video alleging that Trump opponents used Covid-19 to suppress voter turnout and that the left-wing antifa movement carried out the Jan. 6 riots garnered hundreds of thousands of views. YouTube said a separate edited version of that video, which has drawn almost 100,000 views, did not break its standards. Both were reposts of an original video that Google had taken down for breaching its community standards.

On Twitter, scores of users — mostly with small followings — spread conspiracy theories that Democrats and Black Lives Matter protesters were behind the Jan. 6 attacks. These often linked to videos on fringe streaming sites such as Odysee and Rumble, where right-wing influencers also share false claims that hackers compromised voting machines to steal votes away from Trump.

Within alternative social networks like Telegram, white supremacist groups — some with memberships into the tens of thousands and direct ties to domestic terrorist organizations — have frequently posted threats against election officials. They also issued violent calls to arms, telling supporters that people should take to the streets if Democrats try to steal the midterm elections.

None of this content ran with disclaimers, or was moderated for misinformation.

"This problem is getting worse," said Graham Brookie, senior director of the Atlantic Council's Digital Forensic Research Lab, whose team has traced the evolution of domestic extremism after the Capitol Hill riots. "We've got a political violence problem in this country, and it hasn't dissipated after Jan. 6."

Haugen as a game changer

Haugen’s Senate testimony in October added to congressional anger at the tech giants. Among many other disclosures, she revealed that Facebook had shut down its “civic integrity” team and other safeguards against election misinformation soon after the 2020 election. She asserted these actions helped contribute to the spread of the “Big Lie” that led to the insurrection.

"There's many kinds of harmful but legal content like misinformation that can destabilize our democracies," Haugen told POLITICO.

The result was a bipartisan push to require the online companies to offer outside researchers greater access to their data and provide more transparency about the algorithms the platforms use when pushing content to their users.

Coons said he was inspired by Haugen’s testimony, and in December announced draft legislation with Sens. Rob Portman (R-Ohio) and Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) that would require social media companies to give outside researchers access to internal data. Facebook had faced criticism weeks before the 2020 election for blocking New York University from tracking the way the company targeted political ads at users.

Coons said more data would address a major stumbling block for congressional regulation of tech companies: lack of transparency into how the social media companies’ algorithms operate. Similar proposals are also making their way into law in the European Union.

Additionally, Portman said he wants the bill to increase transparency around the big tech companies and provide lawmakers with “high-quality, well-vetted information we need to do our job most effectively.”

Given the partisan disagreements over the 2020 election and tech’s role leading up to Jan. 6, “we are having a hard time finding a course of action,” Coons said. “That’s why I thought focusing first on a neutral, bipartisan transparency and research approach was the concrete next step we can take."

Separately, Rep. Lori Trahan (D-Mass.) is working on a bill she expects to introduce in mid-January to create a Federal Trade Commission bureau run by technology experts to act as a watchdog over tech companies. Trahan said the bureau would issue guidance on ethical platform design and “have the teeth to go after these companies that falsely claim that they follow these guidelines.”

Only one bipartisan bill formally introduced in the current Congress — the Platform Accountability and Consumer Transparency Act (S. 797 (117)) — would require platforms to provide biannual transparency reports on what content they label and remove. This would help provide a greater window into platforms’ content moderation decisions when it comes to material like misinformation.

Jan. 6: ‘Appetizer of what’s to come’?

With Democrats holding a slim House majority and the Senate evenly divided, none of these bills is expected to be a top priority issue for leadership before the midterm elections.

But Trahan said Congress needs to act quickly — and that ensuring access to the online companies’ data is essential for election security going into the midterms. As a stopgap move, Biden's White House is considering piggybacking on voluntary measures already in place in Europe that require social media platforms to provide regular reports on how they combat misinformation.

“I think Jan. 6 is an appetizer of what’s to come if Congress doesn’t act, and the platforms are banking on us not acting,” Trahan said. “They’re putting so much money into lobbying to ensure that we don’t act.”

Yet Washington may need to look inward before any change can occur.

“Congress should be thinking about how they plan to regulate themselves as members cross the line from fair campaigning on differences of opinion to rhetoric that could be incitement or could incentivize attacks or harassment on other members,” said Shannon Hiller, the executive director of Princeton University’s Bridging Divides Initiative, which conducts nonpartisan research on political violence.

“There is a risk that we end up getting into the heat of the campaign season closer to the midterms and realizing that we haven't set those standards and norms together,” she added.

----------------------------------------

By: Mark Scott and Rebecca Kern

Title: Social media booted Trump. His lies about the election are still spreading.

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/2022/01/06/social-media-donald-trump-jan-6-526562

Published Date: Thu, 06 Jan 2022 11:00:36 EST