NEW YORK — To see how the Covid-19 pandemic has changed America’s downtowns, all you have to do is stand in the subway station at Times Square on a weekday morning.

Beneath one of the most iconic intersections in America, trains pull in just a few minutes apart, but even at the height of rush hour they are only half full. The platforms and maze of stairs that lead to the exits are sparsely filled; a stall that sold newspapers and magazines, cigarettes, and soft drinks is shuttered.

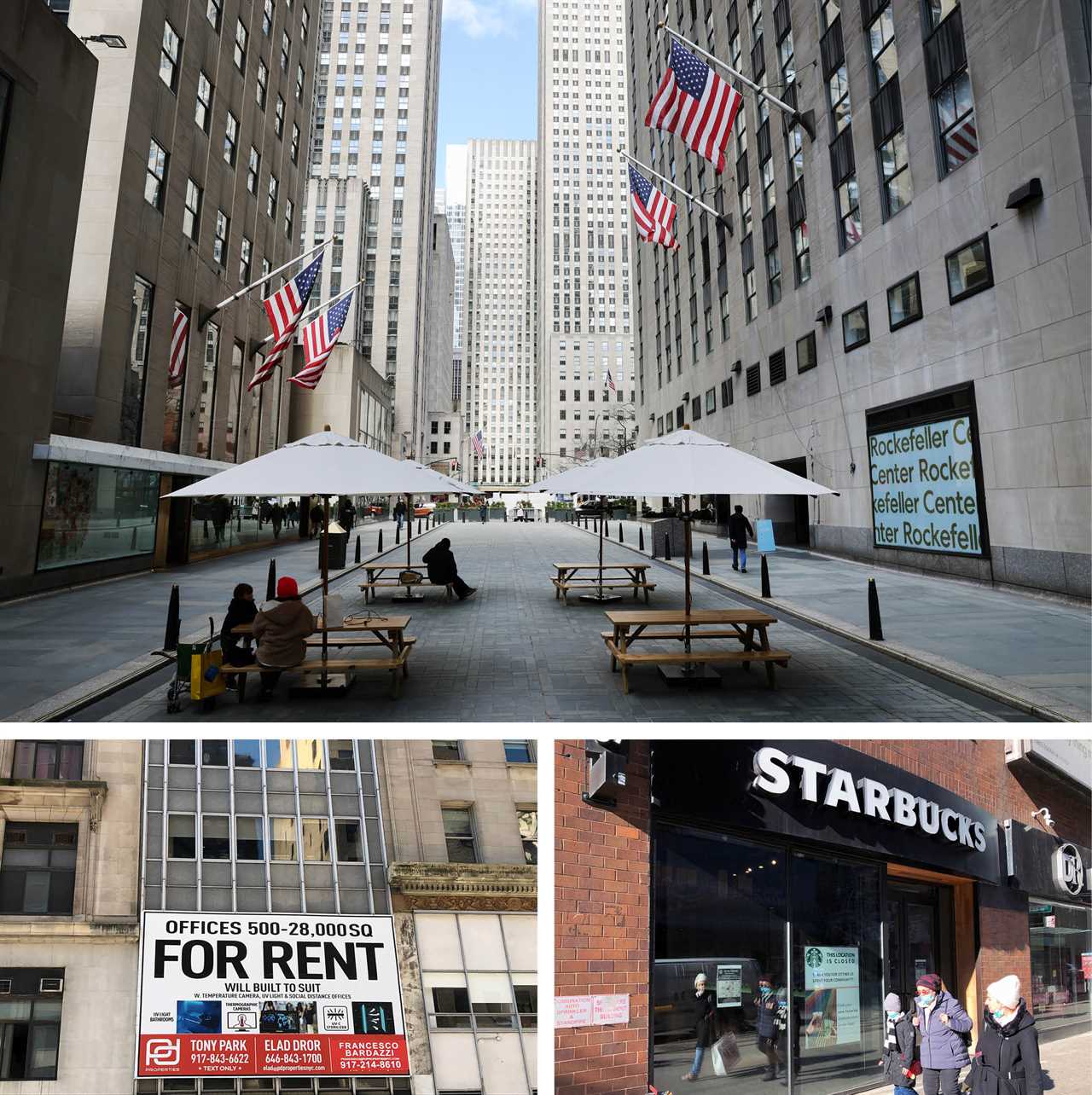

On the streets above, the continued toll of the pandemic is apparent. A former Pret A Manger sandwich shop and Duane Reade pharmacy are available for rent; inside, the spaces are hollowed out but still bear their former logos. At a nearby Starbucks that before Covid routinely saw long lines, just a few people wait to place orders.

“Last year there was nobody in the streets, now maybe 20 percent are coming back,” a halal cart vendor named M.D. Alam told me. Alam said he has been operating the cart for more than a decade on Sixth Avenue near Bryant Park, a short walk from the Bank of America tower, Rockefeller Plaza and other major office buildings. “It’s not like it was before.”

In Times Square and the rest of midtown Manhattan, the office buildings that once fueled much of the area’s activity are still well below pre-pandemic occupancy. Only 28 percent of Manhattan office workers had returned to their desks as of late October, according to a survey from a prominent business consortium, the Partnership for New York City, and just 8 percent were back five days a week. A commanding majority of employers — 80 percent — said they expected a permanent change in their remote work policies, the survey said, while a third anticipated they would need less office space in the next five years.

Pandemic-induced changes in work patterns have taken an especially acute toll on the central business districts of cities — ecosystems that rely on a daily flood of office workers who frequent coffee shops and lunch spots, stop at restaurants and bars after work, and drive public transit ridership. In New York, where office buildings account for a major share of the city’s property taxes, the pandemic has also induced a $28.6 billion drop in taxable market value and cost the city upwards of $850 million in tax revenue.

These impacts pose an existential crisis of sorts for office-centric neighborhoods, and significant consequences for the cities that contain them. Recent studies have suggested remote work will endure. One paper predicted 20 percent of full workdays would occur from home even after the pandemic ends, compared to just 5 percent pre-Covid. The same study said this shift will reduce spending in major city centers by at least 5 to 10 percent compared with pre-pandemic levels.

The upshot is that some commercial space will likely be left vacant long term — at the same time major cities like New York are struggling with a lack of affordable apartments. That has led real estate groups, urbanists, market experts and others to consider whether Covid has created an opportunity to reinvent areas like midtown Manhattan, particularly with new housing. The idea is not without logistical and political challenges, but proponents say it could help breathe new life into areas emptied out by the pandemic.

“Landlords are being very creative trying to improve their buildings, amenitize their buildings, improve the air quality systems,” said Peter Riguardi, chair and president of real estate services firm JLL’s New York tri-state region. “But at this point, without any unforeseen change, there’s still going to be some empty [office] space when we cycle through this, and some of those buildings are going to be ripe for conversion to residential.”

James Whelan, president of the Real Estate Board of New York, said he thinks it’s “inevitable” some portion of the city’s commercial office market, particularly older buildings, “may not be reutilized as commercial office space moving forward.”

How those buildings will be used, and how that transition will occur, will shape America’s cities for decades to come.

High-cost cities like New York, San Francisco and Washington have seen rents rise far faster than incomes over recent decades, and many residents are spending more and more of their monthly paychecks on housing. The problem has been especially acute for poorer households: One recent study found a worker earning New York state’s minimum wage of $12.50 per hour would need to work 94 hours a week to afford a one-bedroom apartment at market rates.

Meanwhile, efforts to build new housing — particularly in prime neighborhoods with sought-after amenities — are routinely met with fierce and sustained pushback from existing residents. In cities where construction costs are high and undeveloped land is both scarce and expensive, where to build new housing and how to finance it have proven to be intractable questions for policymakers.

In New York, Manhattan is the center of jobs, transit and many of the city’s major cultural landmarks, making many neighborhoods within it attractive places to live. But the borough has some of the highest land costs in the city, and much of it is already built out — making empty commercial space a unique opportunity.

“[If an] owner doesn’t see any economic value in investing in a property in order to keep it marketable and maintained as competitive office space, then I think there’s a tremendous opportunity for those buildings to be converted into affordable housing,” said Brett Meringoff, managing partner at the developer Fairstead, which constructs affordable housing and is converting a former hotel into apartments on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

“[Conversions] can be very costly to get done, but the truth is, all of this is costing a lot of money — construction costs are going up, land is scarce, they’re not making any more land on Manhattan,” Meringoff said. “We have to get more creative and find new ways to get access to units or property that can become affordable housing.”

As cities struggle with a shortage of housing, business districts continue to face a shortage of another kind: people.

In midtown Manhattan, business owners say the steep decline in foot traffic since last March has been devastating for their bottom lines, and some local groups see an influx of residents as one answer.

A recent report from the Mastercard Economics Institute, a research arm of the credit card company, found spending at small- and medium-sized businesses in central business districts was down 33 percent compared to 2019 levels, while retailers in residential areas saw an 8 percent increase in spending. An analysis from the Real Estate Board of New York last month found nearly 30 percent of storefronts in a portion of midtown near Grand Central Station are vacant.

Nick Stone, founder and CEO of the coffee chain Bluestone Lane, said in a recent interview customer volume at its locations in midtown were still down roughly 60 percent from before the pandemic, “which is impossible for businesses like us that are reliant on the consistency of patronage.”

Barbara Blair, president of the Garment District Alliance, a group representing property owners and businesses in an area just south of Times Square, said the lack of foot traffic has contributed to fears around crime and made ongoing problems like street homelessness more acute.

“We would love nothing better and our restaurants would love nothing better than having much, much more residential in the neighborhood, and I think it’s a really, really good idea for the people who can convert, if they did convert,” Blair said. “I think residential would really change the tone on the streets and what you see every day and the viability of the retail.”

For New York, this isn’t entirely new territory. Lower Manhattan — the area around Wall Street and Battery Park — went through a similar transition in the 1990s and early 2000s — a transformation that Whelan, of the real estate board, and others said could be a model for midtown.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the commercial office market in lower Manhattan was depressed; the quality of the office stock was seen as outdated compared to other parts of the city and the area was struggling with large amounts of vacant space. An incentive program that would forgive landlords’ property tax payments for a period of time was established in 1995 to encourage conversions to residential; in the subsequent decades, nearly 20 million square feet of office space was turned into apartments, and in the last 20 years, the residential population of the area has nearly doubled, according to an estimate from the Alliance for Downtown New York, a local business group.

“It's fair to say that it’s one of the great success stories in New York. I think it’s, quite frankly, a success story on a global basis in terms of urban revitalization,” Whelan said. “It really helped bring lower Manhattan back in a number of ways.”

Paul Levy, founder and CEO of the business management district Center City Philadelphia, said the repurposing of older commercial buildings has been an accelerating trend in cities around the country, from Philadelphia to Minneapolis to Los Angeles.

“That’s been a 20-year phenomenon in most cities, it just becomes more urgent at this moment,” Levy said. “I think we know how to do this in downtowns; the conversion of buildings from one use to another is something we’ve been doing across the country.”

For all the ways office-to-residential conversions could help revive downtown neighborhoods and assist cities develop sorely needed housing, a range of structural, economic and political factors make them practically difficult to pursue.

In New York, for instance, the same financial approach that worked in lower Manhattan decades ago doesn’t translate cleanly to the present.

Through the pandemic, one saving grace for office landlords has been the fact that leases with companies often span a decade or even longer, meaning many firms won’t need to make major real estate decisions for some time. For a conversion to happen, however, office tenants need to empty out a building, a process that would take several years at least. And the drop in rent and decline in the value of office space would need to be sustained long-term for conversions to present a logical financial path for landlords.

That’s one reason experts say that conversions, even if they are generating primarily market-rate housing, require tax incentives in some form to assist landlords survive during that transition — a tricky proposition in cities like New York where big tax breaks for real estate developers and large corporations have come under heightened scrutiny.

Carl Weisbrod, former head of New York’s Department of City Planning and, prior to that, an architect of efforts to revive lower Manhattan, said he could see that strategy replicated “to a very limited extent” in midtown. But the market for office space hasn’t dropped to the point where it would be financially feasible or desirable on a broader scale — at least not yet.

The condition of office space in lower Manhattan in the 1990s made it so properties, especially older ones, could be purchased “at a very, very inexpensive price,” Weisbrod said. “That doesn’t really quite exist in midtown, where even buildings that are not so new still command pretty high prices.”

The conversions themselves — which involve overhauling the plumbing and electrical systems of a building and constructing new bathrooms and kitchens where there are none — come at a significant cost.

Another problem is structural. John Cetra, a New York-based architect who has worked on numerous conversions, said newer office buildings typically have wider floor plates than older structures, making it more difficult to split them up into individual apartments that meet housing code requirements for windows and other factors. This creates a sort of “donut effect” where the exterior of a building, closer to windows, can be converted more easily, while large shares of space toward the core pose a greater challenge, he said.

“As office buildings got bigger and bigger, with bigger and bigger floor plates, it changed the whole ability to do conversions,” Cetra said.

This is a problem across U.S. cities for office buildings constructed from the 1960s onward, Cetra said. Older structures — those built in the 19th century and early 20th century — typically had smaller floor plates and layouts easier to divide into individual apartments.

In New York, there’s a broad consensus that any plan to facilitate conversions — whether through zoning changes or tax incentives, or both — should require at least some affordable housing, and more than what was required for conversions in lower Manhattan. But the cost and logistical difficulties associated with these efforts also make it harder to ensure apartments for people with low- and moderate-incomes are part of the final result. Past waves of conversions in cities including New York, San Francisco, Chicago and Philadelphia more often yielded condos or higher-end rentals than affordable housing.

Indeed, cities have finite resources to put toward their subsidized housing efforts, and converting office buildings in urban cores is not necessarily the most cost effective way to produce affordable units.

“It’s going to cost a lot more to create a unit for a conversion of an office building in midtown Manhattan than it is to create a unit somewhere else in the city because the real estate is so expensive,” said Rafael Cestero, president of the Community Preservation Corporation, a nonprofit that provides affordable housing financing, and a former head of New York City’s housing department. “And so I think you have to be mindful of the balance of those trade-offs.”

Cestero doesn’t think conversions will ever become a major producer of affordable housing for the city, but still thinks there is an opportunity to create targeted tax incentives and financing mechanisms that can help landlords pursue such efforts where it makes sense to do so. While incentives to help property owners pursue conversions should include an affordable housing requirement, he said, it’s unlikely that a project with exclusively income-restricted, affordable apartments would pencil out.

“Ultimately, I think the principle that we should all agree on is that in a world where we're going to have much more remote work, mixed-use communities where people live and people work are likely to be more vibrant and engaging and the kind of communities that New York wants,” he said. “But it's going to take time and it's going to happen over many, many years.”

----------------------------------------

By: Janaki Chadha

Title: Too many empty offices. Not enough housing. Can cities fix one with the other?

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/2021/11/11/new-york-shrinking-offices-housing-520318

Published Date: Thu, 11 Nov 2021 04:30:44 EST