The abortion debate has upended politics at all levels in the months since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. For months, Democrats were flush with optimism that newly energized abortion-rights voters could swing the midterms in their favor. And Republican candidates, fearing that same backlash to the decision, have backpedaled or softened their stances against abortion rights, angering the advocacy groups who want them to commit to imposing restrictions if elected. In recent weeks, however, voters have told pollsters that abortion rights aren’t as important to them as other issues such as the economy, throwing Democrats’ advantage into question.

In one state, the fight over abortion rights has made Election Day particularly unpredictable: Michigan, which has both a high-stakes abortion rights referendum and a governor’s race where abortion has become central.

POLITICO spoke to nine voters in the state who have been energized by the issue to vote or engage in politics in a wholly new way. Some of them have switched parties; some are engaging in serious activism for the first time; some are casting their first ever ballots.

If Michigan’s proposed constitutional amendment, Proposal 3, passes on Nov. 8, abortion rights will be permanently enshrined in the state’s constitution. If the proposition fails, a 1931 law still officially on the books that bans all abortions, including in cases of rape and incest, could go back into effect, though it’s currently blocked by courts. In the governor’s race, the Democratic incumbent Gretchen Whitmer is facing business executive and conservative commentator Tudor Dixon. Many of Whitmer’s attack ads have been aimed at Dixon’s anti-abortion stance, while Dixon has hit back with accusations that Whitmer is too extreme in her support for abortion rights.

A groundswell of voter enthusiasm has made both of those races hard to predict. Since the Dobbs ruling, voter registrations have surged in the state, particularly among women and young people, according to the data firm TargetSmart. Before the Supreme Court’s June decision overturning Roe v. Wade, more men were registering to vote than women. After the ruling, women out-registered men by 3 points. And while Michiganders younger than 25 accounted for 22 percent of new registrants before the ruling, they now make up 30 percent.

Requests for absentee ballots are also far higher than the last midterm election, prompting the secretary of state’s office to predict record turnout. And people of all ages across the state are getting active in politics in ways they never have before — collecting signatures to get the measure on the ballot, knocking on doors, phone banking and hosting parties to raise awareness about how the election could determine the future of abortion access in the state.

Here are the stories of nine Michiganders who are poised to decide the fate of abortion rights in the state. Many of them say their relationship to political activism has been changed forever by this high-stakes election cycle.

Until the Dobbs decision, Dr. Shari Maxwell, 63, an OB-GYN based in Dearborn, Mich., had never been involved in political activism. A Flint, Mich., native, Maxwell has been practicing medicine for 34 years, and while she’s regularly voted, her long hours and intense work left her little time or energy for volunteering. She had long told herself that simply providing medical care, including abortions, was enough of a contribution.

Then the Supreme Court’s ruling overturning Roe came down in June. The decision hit her hard — to the point where she felt physically sick to her stomach — and she began to think about what she could do outside the exam room.

“I thought the world was rolling backwards,” she said. “I was afraid we might be at risk, even arrested, just for giving patients information.”

At first, Maxwell didn’t know what to do other than continue to educate and console her own patients and colleagues. Then, out of the blue, she got a phone call from Reproductive Freedom for All, the committee organizing voters to support Proposal 3. A representative from the group asked if Maxwell, as a longtime physician and member of the community, would like to appear in some of their PSAs. She was “ecstatic” and felt “no hesitation” about saying yes, she said.

Since then, she’s been urging anyone she encounters to vote in favor of the initiative — lobbying the nurses she works with while waiting for a baby to be delivered, preaching to friends at a recent birthday party, and cornering salespeople at the local mall. “I don’t see a place for politics to be in the exam room,” she said.

Recent college graduate Abby Jones, 25, grew up in Mt. Pleasant, Mich., steeped in the anti-abortion teachings of her Catholic family and community. “I learned a baby was a baby from the moment of conception. That wasn’t even a question,” she said. It wasn’t until Jones got to high school and college, she added, that she met people who had different views on abortion.

She joined anti-abortion groups in high school and college and even traveled once to Washington, D.C., to attend the annual “March for Life.” But until this year, when the future of abortion access in her home state was placed in voters’ hands, she hadn’t turned what she called one of her “greatest passions” into serious political activism. “I haven’t always put [politics] at the top of my priority list until Proposal 3,” she said.

For the past few months, Jones has been canvassing door-to-door with Students for Life to try to persuade voters to reject the proposed constitutional amendment in Michigan. She’s also been putting up signs, appearing on panels and encouraging students at the high school where she teaches to join her.

Now, Jones has a new view on politics. “I’ve gotten so much more interested in how things get on the ballot in the first place, and how citizens can be a part of that — not just candidates,” she said.

Like thousands of others around the country, Beata Lamparski, 69, experienced a political awakening at the 2017 Women’s March, when she took to the streets out of concern President Donald Trump would roll back abortion access nationwide.

There, the active Unitarian Universalist church member from Royal Oak thought about her own experience with a non-viable pregnancy many years earlier that she had to terminate, and worried people who experienced something similar in the future could end up in medical peril.

When she went for her 16-week checkup during that pregnancy, her doctor told her she was no longer carrying a live fetus and would have to have an abortion, Lamparski recalled. “I was shocked,” she said. “But I was treated with such kindness and compassion, and nobody questioned that we needed to have this medical procedure.”

Following the 2017 Women’s March, she continued attending rallies here and there. But it wasn’t until years later, after the Supreme Court majority Trump installed did just as she feared, that she thought of herself as actually being able to influence the outcome of an election.

She and one of her closest friends grabbed clipboards this summer and began gathering signatures to put a constitutional amendment on Michigan’s ballot to undo the state’s pre-Roe ban and protect access to the procedure. Ultimately, they visited more than 30 of the state’s 83 counties. And after the Reproductive Freedom for All campaign gathered more than 750,000 signatures — a record for the state and far more than required — they shifted to encouraging people to vote yes on the amendment in November.

“It felt good to be doing something,” she said, describing hours spent standing outside of theaters and concert venues to talk to hundreds of potential voters. “It’s been a labor of love.”

When Lamparski — Liz Buckner’s friend of 30 years — asked if she wanted to help gather signatures to codify abortion rights in Michigan, the 71-year-old thought back to what life was like before Roe v. Wade.

She thought back to acquaintances who had children they didn’t want in high school and people who had to place kids up for adoption. “It wasn't easy — it haunted them forever,” Buckner said. “Things have changed a lot in 50 years.”

In the following weeks, as she watched state after state surrounding Michigan outlaw abortion in the wake of the Supreme Court’s June ruling, she felt called to volunteer. In addition to gathering thousands of signatures with Lamparski, she’s done phone and text-banking, trained other newbie activists and testified before the State Board of Canvassers as they weighed whether to approve the measure for the November ballot.

“I’ve always been a voter. But I realized I needed to do more than just vote,” Buckner said. “We had to take this into our own hands because our politicians don’t always have our best interests in mind.”

When Caroline Smith graduated from college in 2020, the 24-year-old decided to stay in Michigan and throw herself into anti-abortion protests, even though she didn’t identify with the political leanings of most people working to outlaw the procedure.

“I didn’t used to think there was a space for me in the anti-abortion movement,” she said. “Our movement is seen as all being conservative and religious.” But Smith, she said, is a climate activist, an LGBTQ rights activist and Black Lives Matter activist. “For me, being pro-life is part of my progressive viewpoint,” she said, “because progressives are against injustice and oppression and violence all across the spectrum.”

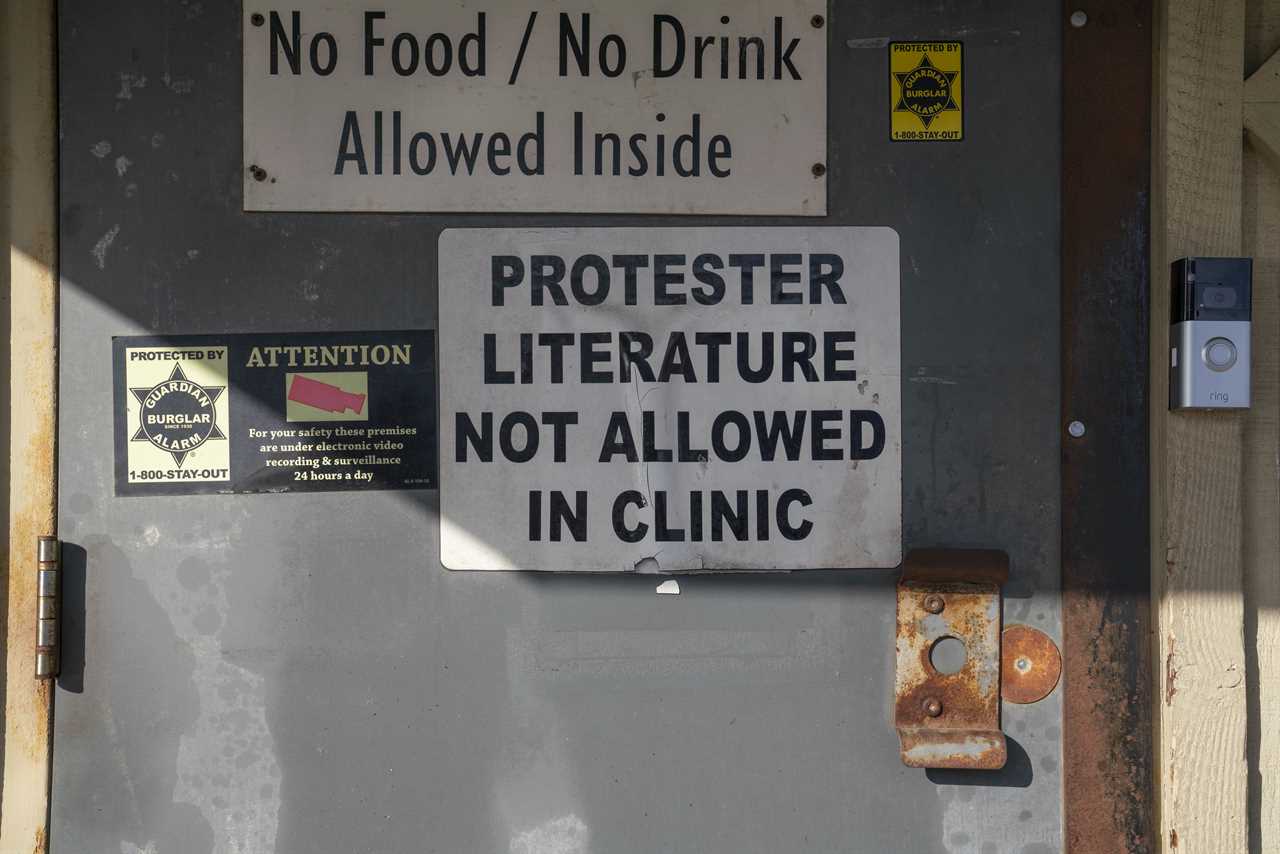

Smith has spent the last few years organizing protests, including planned disruptions of pro-abortion rights rallies, demonstrations outside abortion clinics, and even instances where they’ve entered clinics to try to dissuade patients from going forward with the procedure. Several members of her organization — Progressive Anti-Abortion Uprising — have been arrested for such actions.

When the fight began over Michigan’s ballot initiative earlier this year, Smith, who always thought herself better at agitating and organizing activists, didn’t feel comfortable or interested in engaging in electoral work. But fear that the amendment protecting abortion rights would pass and Michigan would “become the most pro-abortion state in the country,” she said, changed her mind. For months, she’s been knocking on doors, training other volunteers, speaking at rallies opposing Proposal 3 and consulting with other anti-abortion groups on their messaging and tactics related to the ballot campaign.

“Because of that urgency, I didn't even second guess that this is what I needed to do. Putting myself out of my comfort zone will be worth it if thousands of lives can be saved.”

Krystal Carpenter, 43, identified as a staunch Republican and voted that way from her 18th birthday until this year, when she turned 42 and watched GOP leaders cheer as the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

Carpenter knew about the ruling as soon as it came on because, at the time, she had her TV turned on to Fox News 24/7.

“I called my husband, hysterical,” she said. “I felt disappointed, disrespected and hurt by the party I supported my entire life. Why would the party I was born and raised into, that I’ve given my time, money and vote to, turn their back on me and say I can’t make this decision?”

Two days later, Carpenter changed her party registration so she could participate in the Democratic primary. She also started writing letters to every elected official she could think of, from her state lawmakers and governor to Biden and each member of the U.S. Supreme Court. Only one person responded out of the dozens she contacted — Whitmer, who invited her to participate in an October listening session on abortion rights.

There, she told the governor and the other Michigan women at the event that the fall of Roe hit her particularly hard because she had had an abortion as a teenager after becoming pregnant as a result of a sexual assault — a decision she feels allowed her to thrive and become a mother later, when she was ready.

“If I had to give birth at 17, would I have quit school? Would I have been resentful of my children? Would I have committed suicide? Would I have fallen into alcohol or drug addiction?” she wonders. “I know that what made me a fantastic mother is that the choice was mine.”

For the next few weeks, Carpenter says she will be knocking on doors, making phone calls and attending rallies for Whitmer and the ballot referendum on abortion rights. After that, regardless of the outcome of the vote, she’s unsure whether she will ever return to the GOP.

“I truly feel like after the vile hatred I have been given from my former political party … I don't know if I will ever be able to vote for them again,” she said. “The one time it mattered, they abandoned me.”

Austin Fox, 30, tried his hand at many different things before finding his calling teaching Catholic high schoolers and organizing religious youth retreats — bouncing from state government work to covering sports for a local newspaper.

But the Westphalia, Mich., native had never before volunteered for a political campaign until earlier this year, when the abortion rights constitutional amendment was approved for the November ballot.

“It lit a fire down inside me,” he said. “It was a no-brainer to make sure we were proactive and did as much as we could to spread the word about how dangerous it would be if it passes.”

Since then, on top of his work as the director of religious education at his church, he’s been posting on social media against the ballot initiative, recording podcasts, handing out pamphlets, phone banking and organizing teams of volunteers to knock on doors. Fox says the campaign has opened his eyes to the importance of political activism and made him want to continue applying his personal religious beliefs to influencing public policy in the future.

“This is the most important vote I’ve ever seen,” he said. “But I’ll definitely stay involved down the road on anything that involves abortion or other moral issues.”

Michigan State University sophomore Joshua Mostyn, 19, said he knew for years that the first election he’d be old enough to vote in would be historic. As he watched Trump ascend to the White House and transform the Supreme Court with conservative appointees, he predicted that the fall of Roe v. Wade was only a matter of time. And by the time it came to pass, the aspiring opera singer felt that the stakes of his first vote — sent in by mail weeks ahead of Election Day — couldn’t be higher.

“If we don’t get this constitutional amendment in place, we’ll have no abortion ever, which is very dangerous,” he said. “People are going to keep having abortions but it’ll be in a back alleyway. People will die.”

Mostyn has been frustrated, however, that many of his fellow students appear confused or apathetic in the lead-up to the midterms. “A lot of people just don’t care, which is sad,” he said. For those who want to vote but don’t know how, he’s walked them through how to register and cast a ballot.

Some have required more convincing. “Other people just assume that our governor is going to win, and the referendum is going to pass, so they think there’s no point in voting,” Mostyn said. “But I try to tell them, if people don’t vote, that won’t happen.”

Stay-at-home mother of three Jessica Leach, 37, thought of herself, for decades, as a textbook Republican — though, in her words, not a “hardcore” one. She and her husband, a Marine Corps veteran, voted for Trump in 2016 but not in 2020. They were raised Catholic, but no longer attend church. She identified as personally anti-abortion but didn’t want to impose that stance on anyone else.

The GOP’s pitch of “less government, more freedoms, more rights” always appealed to her, which is why she felt gutted when Republicans and their hand-picked judges overturned Roe v. Wade. “It doesn’t resemble the party I signed up for,” Leach said. “There are plenty of ways to decrease abortions if you want to do that. But this isn’t it. This is just about power and control.”

When Roe fell, she thought back to her first pregnancy 17 years ago that she considered terminating out of concern she wouldn’t be a good mother. She ultimately decided to see it through.

When she first discovered the unintended pregnancy, she recalled, she went to a church-run clinic with her boyfriend, where “they just started pushing scripture at us and telling me not to have an abortion.” Turned off by the pressure campaign, she then visited an abortion clinic, and said the staff there gave her “all the information I needed to make the best choice for me and my life.”

“After seeing the ultrasound and loving it, I decided to keep it,” she said. “I had the privilege to go home pregnant.”

This year, the thought that Michiganders might not have that choice in the future made her change her party registration, lobby her friends and family to vote for the abortion rights referendum, and volunteer to get out the vote for the referendum and for Whitmer, who has centered her reelection campaign around the issue.

“I love being a mom, but I wonder if I would love it so much if I hadn't had a choice,” she said. “If you ban abortion, will you be tampering with people’s ability to truly love motherhood?”

Photo editing by Katie Ellsworth.

----------------------------------------

By: Alice Miranda Ollstein and PHOTOGRAPHS BY SARAH RICE FOR POLITICO

Title: These Abortion Voters Could Transform Michigan

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/11/04/michigan-abortion-midterm-election-voters-00063553

Published Date: Fri, 04 Nov 2022 03:30:00 EST