Joe Biden says that America’s greatest long-term challenge overseas comes from China. Confronting Beijing is the work of generations, he argues. It’s the battle that your grandchildren will study in college: Will democracy or autocracy prevail across the globe?

The fight for economic superiority in Asia is a critical component of this contest. But 13 months into the Biden presidency, the administration’s plan for competing in the region consists of a single 51-word paragraph. In an October statement, Biden announced he would create what he calls an “Indo-Pacific Economic Framework.” When asked now about Biden’s plans to take on China’s economy, administration officials still refer to the October description of the framework. They say they are only at the start of a months-long process to develop an Asian economic plan — but as yet, that paragraph is the closest thing to a public strategy that the White House has announced.

What is the framework exactly?

The paragraph lists a half-dozen topics where the U.S. will seek agreements with Asian nations, including on infrastructure, climate and digital technology. But so far, the White House has not released any supporting documents or held any press briefings to explain its plans, and Biden officials acknowledge they haven’t come up with specific proposals yet.

A one-page White House memo from the fall labeled “USG Talking Points for Foreign Partners” — which has not been previously reported — makes clear what the framework isn’t, however. It’s not a free-trade deal and it won’t give Asian nations broader access to U.S. markets through tariff cuts or other concessions. “IF RAISED” in discussions with foreign governments, the memo instructs American diplomats in capital letters, “To be clear, this initiative will not include new market access commitments.”

Biden’s China policy captures the bind the administration finds itself in. The post-Trump politics of trade make it politically treacherous to push to open up the American market abroad. Biden’s narrow win in the Rust Belt was based partly on his promise that he’d protect American jobs, which means keeping a strict lid on foreign competition. But that political red line is also a big handicap in the race with Beijing. Those are exactly the commitments Asian nations say they need to export more to America and limit their dependence on China.

One Biden aide said a vague proposal was the only way that squabbling officials could come to a public consensus.

“They’re paralyzed,” says Derek Scissors, a China expert at the American Enterprise Institute who has long pushed for an aggressive U.S. stance in Asia. “They know there is something important they need to do, but the people involved don’t have the nerve to do anything.”

Be patient, counter a raft of administration officials and their supporters on Capitol Hill. Biden always intended to work first on domestic policies, including investments that will help the U.S. compete with China, before moving into trade issues, they say. Interagency work on the framework will kick into high gear over the next six weeks. Officials are planning a public release of a fuller version of the framework by March 31, although that could slip.

“President Biden doesn’t just say that this is the challenge of this century,” says Democratic Sen. Chris Coons, a close Biden ally from Delaware. “He is acting on it and focusing on it.”

But with the administration also split into factions, the politics of trade are thornier than ever. Biden is hemmed in between what voters at home expect and what overseas allies want. The consequence, according to a series of interviews with Biden officials, lawmakers, diplomats, Hill aides and advocates, is that efforts to create a pan-Asian plan to elbow China aside have barely moved at all.

The administration faces daunting politics in trying to assemble a muscular economic approach in Asia.

The free trade consensus on Capitol Hill shattered long ago. Many Democrats turned against trade deals in the 1990s with the North American Free Trade Agreement. Large swathes of Republicans joined them under Donald Trump’s America First policies, although lawmakers from both parties approved modest additions to NAFTA in 2020. When it comes to Congress, on both sides of the aisle, trade deals are out and China-bashing is in.

“You’re seeing a battle for the soul of the American worker with both political parties,” says Rep. Mike McCaul of Texas, the ranking Republican on the House Foreign Relations Committee.

In Asia, the political constraints are reversed. Asian governments want trade deals — specifically for the United States to join a trade pact in Asia that Barack Obama couldn’t convince his party to support, and which Trump rejected on his first day in office, the Trans-Pacific Partnership. And attacking China is definitely not on the agenda. No Asian nation wants to be seen as choosing sides between Washington and Beijing. One Asian diplomat in Washington said China should be able to join any new framework deal — a very tough sell in Washington.

“If this is pitched as an anti-China initiative,” the diplomat said, “I doubt many countries will be willing to sign on.”

According to some Biden officials and those who follow the White House closely, the administration itself is divided on how to proceed. The internal fights haven’t reached the bitter peaks of the Trump administration where self-described anti-free trade nationalists openly battled so-called globalists. Those fights sometimes reached slapstick levels, such as when White House trade adviser Peter Navarro got into a screaming match with his nemesis, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, on the lawn of a Beijing conference center as Chinese officials watched nonplussed.

The more genteel Biden crowd is divided into three camps. The old globalist/nationalist labels don’t quite fit because they all agree on multilateral engagement (globalist) and they haven’t lifted Trump’s tariffs (nationalist). But there are big differences among them.

In one corner are the trade expansionists who want to tie Asian nations closer to the U.S. with trade deals. They include White House Asia coordinator Kurt Campbell, Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

Then there’s the more labor-friendly faction, whose overriding goal is to make sure trade deals don’t hurt workers already battered by China trade and are more willing to use tariffs and quotas to protect them. They include U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai and some at the White House Council of Economic Advisers.

The third camp looks at trade through a political lens. Scrapping with China economically, they fret, could screw up other administration priorities like easing inflation or supply chain bottlenecks. That group includes White House chief of staff Ron Klain, National Security and National Economic Council Director Brian Deese.

The result: inaction. Policy options are debated, teed up for release and then pulled back — a kind of vaporware China economic policy.

A digital trade agreement pushed by Campbell and others was slow-walked by Tai, who is weighing whether a deal could be made more worker-friendly, say administration officials and outsiders tracking the debates. A plan by Tai to launch a trade case against China’s use of industrial subsidies was dropped, in part, because of concerns it would interfere with her upcoming discussions with the Chinese on enforcing the 2020 Phase One trade deal Trump had negotiated. A fall 2021 China speech by Biden, discussed in the White House, never materialized.

A White House spokesperson denied any paralysis. “The White House role is to elevate and coordinate all views on the best ways and opportunities to deliver on that vision for the American people every day, and that’s our sole focus,” he said.

A spokesperson for the U.S. Trade Representative’s office says that Tai has been regularly conferring with Asian nations about a digital trade pact. As for the trade case on digital subsidies, she “would use every tool in the toolbox” to address unfair trade practices, he added.

“Our objective is not to escalate trade tensions with the PRC,” he says, using the abbreviation for the People’s Republic of China, “or double down on the previous administration’s flawed, chaotic and unilateral approach which alienated our allies and partners.”

The origins of Biden’s terse 51-word strategy statement lie in a White House debate that began in the summer over how to open an economic front against China and deal with Asian criticisms that the administration lacked a trade policy.

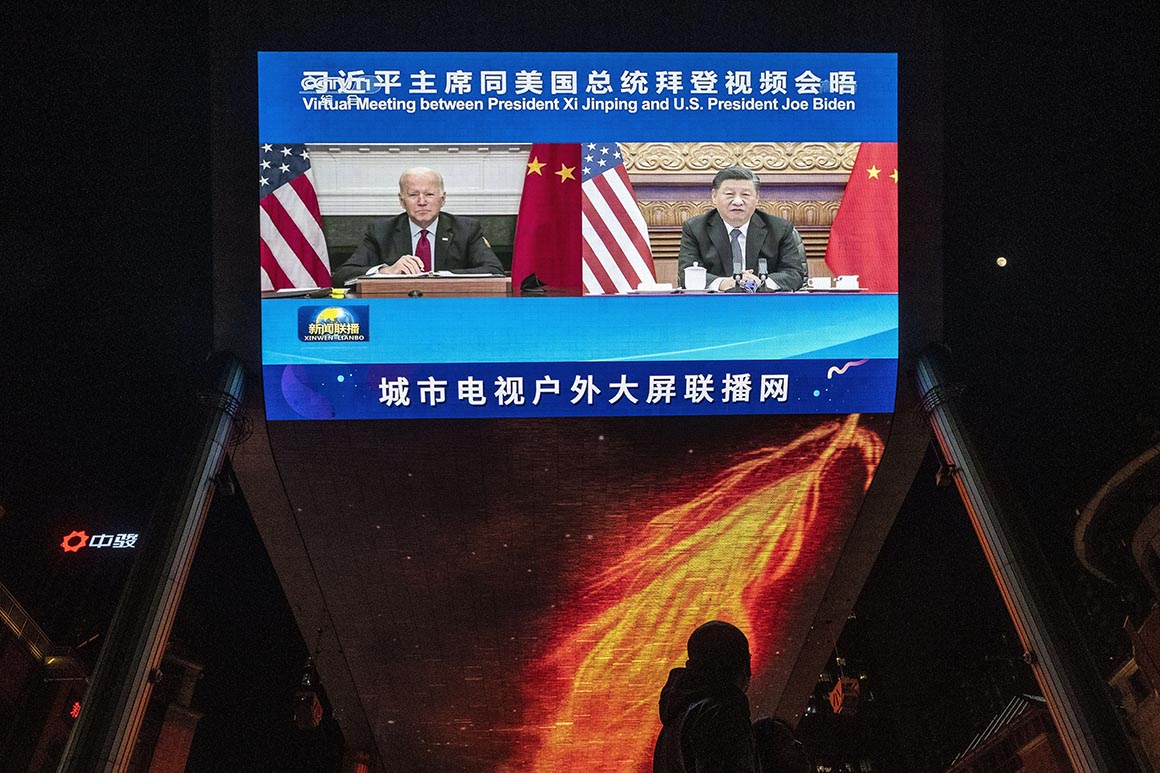

It was written in the fall, according to administration officials and those who closely track the White House, to fill a pressing need: The president was scheduled to participate in three virtual summit meetings in the fall of 2021 with leaders of Asian nations, who had been lobbying intensively for a trade plan out of Washington. The administration hadn’t released any plans for a regional trade agenda.

Meanwhile, China was advancing on the trade front. Beijing negotiated a trade deal with fast-growing Asian nations, called the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which cuts tariffs among member nations and leaves out the United States. China also applied to join the TPP, which the U.S. had spurned and which had been rechristened Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

The U.S. needed an economic plan — Biden had to show he was moving to counter China.

Jennifer Harris, a National Security Council economic official who has long been skeptical of free-trade pacts, was asked to come up with something the president could announce. She cobbled together a list of six areas the administration was working on already — digital technology, supply chains, climate, infrastructure, worker standards and what’s known as trade facilitation, meaning easing shipping problems.

These were the areas the U.S. “will explore with partners” as part of a new Indo-Pacific economic framework, the president told Asian leaders during an October speech at the East Asia Summit. He didn’t mention China, whose premier, Li Keqiang, attended the virtual meeting. But the message was clear. This was the United States’ long-delayed entry in the race with China for the economic allegiance of Asian nations.

Although Biden has adopted some of Trump’s trade tactics, including keeping tariffs on most Chinese imports, his framework rejects how Trump tried to confront China. The Trump administration battered Beijing one-on-one with tariffs on a scale not seen since the 1930s and blocked exports of some advanced technology.

But that economic firefight didn’t get China to change its state-led policies of sealing off some markets to foreign competition, pressuring Western companies to hand over technology and massively subsidizing state-owned firms. China also didn’t come through with the big purchases it promised in the Phase One trade deal.

Trump’s efforts left the Biden team with a mess. The administration faces an unappetizing choice about what to do about the Phase One shortfalls: Increasing tariffs to punish China would hurt U.S. manufacturers that rely on imported parts; giving China a pass would give Republicans political ammunition to assail the administration. A decision is expected shortly.

Instead of a direct confrontation, the Biden team is returning to the Obama model of trying to influence China from the outside by lining up allies in the region. The mantra inside the White House: “Shape the environment around China.”

Except that strategy didn’t yield much under Obama. China’s economic influence continued to grow. And unlike Obama, Biden is entering the arena without America’s most alluring attraction: the promise of more access to the U.S. market, still the world’s largest.

Instead, the U.S. will look to build alliances based on areas of common interest, like financing infrastructure projects in the region, developing secure supplies of minerals needed to make advanced electronics or writing agreements to ease digital commerce.

Todd Tucker, director of governance studies at the Roosevelt Institute, a left-leaning think tank, says the framework represents a nod to political reality. Congress balks at free-trade pacts. Better to find sectors where allies want to work together, including signing up Japan and others to join a U.S.-European Union deal to put tariffs on steel made in a carbon-intensive fashion.

Biden officials say they are looking for an economic initiative to match the national security moves they have made. That includes the briefly contentious deal with Australia and the United Kingdom to build nuclear submarines to patrol the Pacific as well as lining up support from Japan and others to deter China from invading Taiwan.

“It’s time to move past outdated models and instead strengthen trade and investment in the region in a manner that promotes good-paying American jobs,” says the NSC spokesperson.

Australia’s ambassador to the U.S., Arthur Sinodinos, says the framework is a good first step. “It’s important to complement [security arrangements] with trade and economic engagement,” he says.

According to the talking points put together around the time of the framework’s announcement, the U.S. planned to pitch the proposal initially to eight nations — Australia, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore and Vietnam — conspicuously leaving out China.

Raimondo and Tai would lead the effort, although Commerce and USTR are longtime bureaucratic rivals. And whatever they manage to put together won’t need congressional approval, the document said — meaning that the administration didn’t expect to have to make any changes in U.S. law, like cutting tariffs or changing regulations to encourage Asian imports.

A one and one-half page “Concept Note,” also undisclosed until now, gave a one or two sentence description of each category in the proposed framework and made clear that the framework “need not be a binding agreement.” That was it. No specific proposals.

The lack of detail and action has frustrated business groups. “A year in, where is the trade agenda? Nowhere,” says the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s executive vice president Myron Brilliant.

In November, Raimondo, Tai and Blinken jumped on planes to pitch the framework and get feedback from to government officials in Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, New Zealand and Australia. In Tokyo, Tai met with three different ministers. The three U.S. officials were largely mum in public though Raimondo gave hints of what they were up to, like a game show host describing a prize behind different doors.

The framework would be more “robust” and “comprehensive” than the usual free-trade agreement and “a bit less constrained,” she said at various stops. As for rejoining TPP, she said this in a Singapore interview: “For various reasons, you know, that is not going to happen now” — leaving open the possibility it could happen sometime later.

That was sufficient to raise alarms on Capitol Hill among free-trade skeptics suspicious of what the administration was up to. To ease concerns, Commerce arranged a virtual meeting in mid-December with its chief economist, Ronnie Chatterji to talk with House Ways & Means staff, which made things worse, say Democratic staffers. To a barrage of questions, he largely offered Commerce’s public statements and at one point wouldn’t even say which countries had been contacted about the Framework. “The scars of TPP are still raw,” says a Democratic staffer who dialed in. “People were frustrated.”

A Commerce official says that Chatterji hadn’t expected to be asked to give a full briefing on the framework.

Since returning from Asia, Raimondo has assured lawmakers, unions and others involved in the trade debate that they will be consulted throughout the policymaking process. Meetings with Asian governments desperate for information also continue, though U.S. officials don’t have specifics to offer them. In mid-January, Biden chatted by teleconference with Japan’s prime minister who said he would promote the initiative in Asia, the White House said.

“Every two days we are asking the administration about the plan,” says a Japanese diplomat. “Other countries are doing the same.”

The natural rhythm of Washington wonkery has also kicked in. USTR is working on a trade component of the framework, which involves digital trade, agricultural regulation along with labor and environmental commitments, said a Biden official. Commerce oversees much of the rest as it seeks to put what official after official calls “meat on the bones.” Both agencies coordinate through the NSC. Outside trade experts are making suggestions about how to flesh out the plan.

Among the ideas in a 13-page paper by Matthew Goodman and William Reinsch, Democratic trade experts now at the Center for Strategic and International Studies: Use the framework to push for the stalled digital service trade deal in Asia, and finance renewable energy projects, including deploying technology to inject atmospheric carbon dioxide into concrete.

So far, the plan is vague enough that Coons could put together a bipartisan letter of support from five other lawmakers, including Republican free-trader Sen. Todd Young of Indiana and Democratic free-trade skeptic Sen. Jeff Merkley from Oregon. The letter pushed for a digital trade pact that would protect privacy and assure the flow of information across borders.

“The purpose of this letter was to encourage the administration to put forward some more specific policies,” says Young.

But the more specific the plan gets, the more the political constraints kick in. Coons, for instance, backs tariffs on imported goods made through carbon-intensive processes, which would penalize China — a proposal bound to kick up opposition from importers and other business interests and could also disadvantage potential U.S. allies like India or Vietnam.

Meanwhile, labor unions are suspicious of a digital trade agreement, fearing that enhanced communications could make it easier to automate jobs and shift them overseas. “We know where the trouble spots are for us,” says Dan Mauer, government affairs director for the Communications Workers of America.

And as the TPP panic attack on Capitol Hill in December shows, there is deep suspicion among free-trade critics that the administration will use the framework to try to rejoin the TPP or start negotiations on a new broad trade deal. Activists say they are ready for a battle.

“There are some never-learn ideologues trying to use this process to revive the corporate-rigged trade pact model in general and TPP in specific,” says Lori Wallach, a veteran anti-free trade campaigner who works closely with Democratic lawmakers.

The White House knows it has a lot of work to do in Washington as well as in Asia. “The United States is going to have to continue to step up its game,” Campbell, the White House Asia coordinator, said in early January at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “I think we well understand inside the Biden administration that 2022 will be about these engagements comprehensively across the region.”

----------------------------------------

By: Bob Davis

Title: Inside the Biden Administration’s Unwritten Plan to Confront China

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/01/31/biden-china-trade-politics-00003379

Published Date: Mon, 31 Jan 2022 04:30:00 EST