The war began in the early morning hours with a massive bombardment — China’s version of “shock and awe.” Chinese planes and rockets swiftly destroyed most of Taiwan’s navy and air force as the People’s Liberation army and navy mounted a massive amphibious assault across the 100-mile Taiwan Strait. Having taken seriously President Joe Biden’s pledge to defend the island, Beijing also struck pre-emptively at U.S. and allied air bases and ships in the Indo-Pacific. The U.S. managed to even the odds for a time by deploying more sophisticated submarines as well as B-21 and B-2 stealth bombers to get inside China’s air defense zones, but Washington ran out of key munitions in a matter of days and saw its network access severed. The United States and its main ally, Japan, lost thousands of servicemembers, dozens of ships, and hundreds of aircraft. Taiwan’s economy was devastated. And as a protracted siege ensued, the U.S. was much slower to rebuild, taking years to replace ships as it reckoned with how shriveled its industrial base had become compared to China’s.

The Chinese “just ran rings around us,” said former Joint Chiefs Vice Chair Gen. John Hyten in one after-action report. “They knew exactly what we were going to do before we did it.”

Dozens of versions of the above war-game scenario have been enacted over the last few years, most recently in April by the House Select Committee on competition with China. And while the ultimate outcome in these exercises is not always clear — the U.S. does better in some than others — the cost is. In every exercise the U.S. uses up all its long-range air-to-surface missiles in a few days, with a substantial portion of its planes destroyed on the ground. In every exercise the U.S. is not engaged in an abstract push-button war from 30,000 feet up like the ones Americans have come to expect since the end of the Cold War, but a horrifically bloody one.

And that’s assuming the U.S.-China war doesn’t go nuclear.

“The thing we see across all the wargames is that there are major losses on all sides. And the impact of that on our society is quite devastating,” said Becca Wasser, who played the role of the Chinese leadership in the Select Committee’s wargame and is head of the gaming lab at the Center for a New American Security. “The most common thread in these exercises is that the United States needs to take steps now in the Indo-Pacific to ensure the conflict doesn’t happen in the future. We are hugely behind the curve. Ukraine is our wakeup call. This is our watershed moment.”

The problem has come into sharp relief only in the last few years as Russia invaded Ukraine, leading to a prolonged war that has drained U.S. munitions stockpiles, and China dramatically escalated both its military spending and aggressive rhetoric against Taiwan. In the last year the U.S. has allocated nearly $50 billion in security aid to Kyiv, possibly cutting further into its deterrent against China. In other words, the failure to deter Vladimir Putin from invading Ukraine and the stress this has put on the U.S. defense industrial base should be sounding alarms for the U.S. military posture vis-a-vis Taiwan, many defense experts say. Yet critics on both sides of the aisle say the Biden administration has been slow to respond to what is minimally required to prevent an Indo-Pacific catastrophe, which is the need to rapidly build up a better deterrent — especially new stockpiles of munitions that would convince China it could be too costly to attack Taiwan.

“There is a recognition of the challenge that goes to the top of the Pentagon, but across the board there is more talk than action,” says Seth Jones, a former Obama-era defense official who compiled a report on one of the wargames conducted at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

But a swift response may not be possible, in large part because of how shrunken the U.S. manufacturing base has become since the Cold War. All of a sudden, Washington is reckoning with the fact that so many parts and pieces of munitions, planes, and ships it needs are being manufactured overseas, including in China. Among the deficiencies: components of solid rocket motors, shell casings, machine tools, fuses and precursor elements to propellants and explosives, many of which are made in China and India. Beyond that, skilled labor is sorely lacking, and the learning curve is steep. The U.S. has slashed defense workers to a third of what they were in 1985 — a number that has remained flat — and seen some 17,000 companies leave the industry, said David Norquist, president of the National Defense Industrial Association. And commercial companies are leery of the Pentagon’s tangle of rules and restrictions.

“Unfortunately, the more you dig under the hood the more problems you see,” said a senior Democratic defense expert in the Senate who was granted anonymity because he was not allowed to speak on the record for his boss. “This is largely a function of the post-Cold War period being focused on efficiency. Since the Gulf War we came to expect too much from smart munitions. We haven’t needed stockpiles or found ourselves critically low on spare parts. So we’ve decreased the wiggle room.” At a military conference earlier this year, the Navy’s intelligence chief, Rear Adm. Mike Studeman, called the problem “China blindness,” saying: “It’s very unsettling to see how much the U.S. is not connecting the dots on our number one challenge.”

The administration’s response, including the fiscal 2024 defense authorization bill, was also delayed because of the protracted negotiations over Biden’s budget and the debt ceiling. Sen. Jack Reed, the Democratic chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee, had been planning to hold hearings on America’s defense industrial base, but put those plans off because of the time being devoted to budget and debt dickering.

The most urgent task is to manufacture and move massive numbers of missiles and other high-tech munitions to East Asia to shore up the U.S. deterrent against China, says Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-Wis.), chair of the Select Committee. What is most needed: far more Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missiles (JASSMs), Long Range Anti-Ship Missiles (LRASMs), Harpoon anti-ship missiles, Tomahawk cruise missiles and other munitions, Gallagher said.

“You need this to be prioritized at the SecDef [secretary of defense] level,” Gallagher told me in an interview in early May. But when Gallagher asked Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin questions about Taiwan’s defenses at a recent hearing, “he couldn’t really answer,” Gallagher said. “I asked Austin point blank, ‘What is your highest priority?’ and he responded with all this jargon about readiness levels.” Gallagher said the Pentagon should offer prime missile contractors such as Lockheed Martin a slew of new multi-year contracts.

The Pentagon declined to comment, but at a meeting of the Council on Foreign Relations on May 3, Under Secretary of Defense William LaPlante said the Biden administration and its allies in Europe and Asia were moving quickly to fill the gaps.

“We’re in the middle of a pivot, and that’s very exciting to see,” said LaPlante, who added that he just returned from a meeting of NATO and “all we’re talking about is our industrial base.” Biden’s proposed defense budget plans for the first time to procure missiles and other munitions with multi-year contracts, as is now done with planes and ships. LaPlante said the administration is beginning to deliver some large weapons systems to overseas allies in record time. New NATO member Finland, for example, got approval for 65 F-35 fighters only in February of 2020 and is slated to have the planes delivered next year.

Some U.S. intelligence and defense officials fear that Beijing understands the deficiency in American readiness all too well and could try to exploit it by attacking or blockading Taiwan in the next few years. Earlier this year, CIA Director Bill Burns said the United States believes that Chinese President Xi Jinping has ordered his military to be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027. This was so, Burns said, despite the likelihood that Xi was “surprised and unsettled” by the “very poor performance” of the Russian military in Ukraine.

In April, China’s military completed three days of large-scale combat exercises around Taiwan that rehearsed blockading the island and said in a statement it is “ready to fight … at any time to resolutely smash any form of ‘Taiwan independence’ and foreign interference attempts.” The actions followed U.S. pledges to arm up Taiwan and Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen’s diplomatically risky meeting on U.S. soil with U.S. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy. In recent months several Chinese fighter jets have buzzed American military aircraft over the South China sea. Barring a confrontation over Taiwan, however, Xi and other senior Chinese officials have said they do not want war with the United States. Relations between the two powers should not be a “zero-sum game where one side outcompetes or thrives at the expense of the other,” as Xi told Biden at their last bilateral meeting in Bali in November, according to a Chinese Foreign Ministry statement.

So far, China’s actions seem to be speaking louder than such words. LaPlante conceded that fears Beijing is calculating it must act against Taiwan sooner than later are “a very valid concern. It is always a question that is on everybody’s mind.” In an interview, LaPlante said that sense of urgency is why Biden has invoked the emergency Defense Production Act, enacted during the Korean War, to rebuild and expand the nation’s domestic hypersonic missile industry. This is a key area of Chinese advancement, and U.S. officials fear that Beijing seeks to use hypersonics to push U.S. ships and bases out of close range in the Asia-Pacific region.

Many critics say it’s not enough. “We’re in a window of maximum danger,” says Christian Brose, a former senior aide to the late Sen. John McCain, who for years was a lone voice in the wilderness warning against the Chinese and Russian buildup. “We could throw a trillion dollars a year at the defense budget now, and we’re not going to get a meaningful increase in traditional military capabilities in the next five years. They cannot be produced.”

One of the reasons, again, is that China and other countries — not all of them friendly — make and supply a lot of that stuff now. Over decades of what many say was delusional thinking by both political parties about turning China into a friendly “stakeholder” in a peaceful international system, Washington heedlessly ceded shipbuilding, aircraft parts and circuit boards over to China and other cheap overseas labor forces. America’s new F-35 fighter jets, for example, contain a magnet component made with an alloy almost exclusively manufactured in China. China also totally dominates machine tools and rare earth metals, essentials for manufacturing missiles and munitions, as well as lithium used in batteries, cobalt and the aluminum and titanium used in semiconductors. While Beijing has made new advances in explosives, most American military explosives are made at a single aging Army plant in Tennessee, Forbes reported in March.

“While they were industrializing, we were deindustrializing,” says Brose. Today China commands some 45 percent to 50 percent of total shipbuilding globally, while the United States has less than one percent. “Given those numbers, explain to me how the United States is going to win a traditional shipbuilding race with China?”

“The bottom line is this whole problem was decades in the making,” added Brose. “It’s not something that just kind of crept up on us and surprised us over the last couple of years.”

The Biden administration can hardly bear most of the blame. For decades after the Cold War, Washington was lulled into defense doldrums from which it is still not fully awakened. The mid-to-late 1990s were an era of American triumphalism, when the prospect of traditional warfare seemed remote. The Berlin Wall fell in 1989, and by the end of 1991 the Soviet Union had disintegrated. Most officials expected a “peace dividend”: A deflated post-Soviet Russia was seeking U.S. economic advice in shifting to a market economy, and under the Nunn-Lugar program, Moscow was cooperating in eliminating nukes. Washington hopefully brought China into the World Trade Organization, expecting Beijing to observe at least some rules in the U.S.-dominated international system — a policy supported by both political parties.

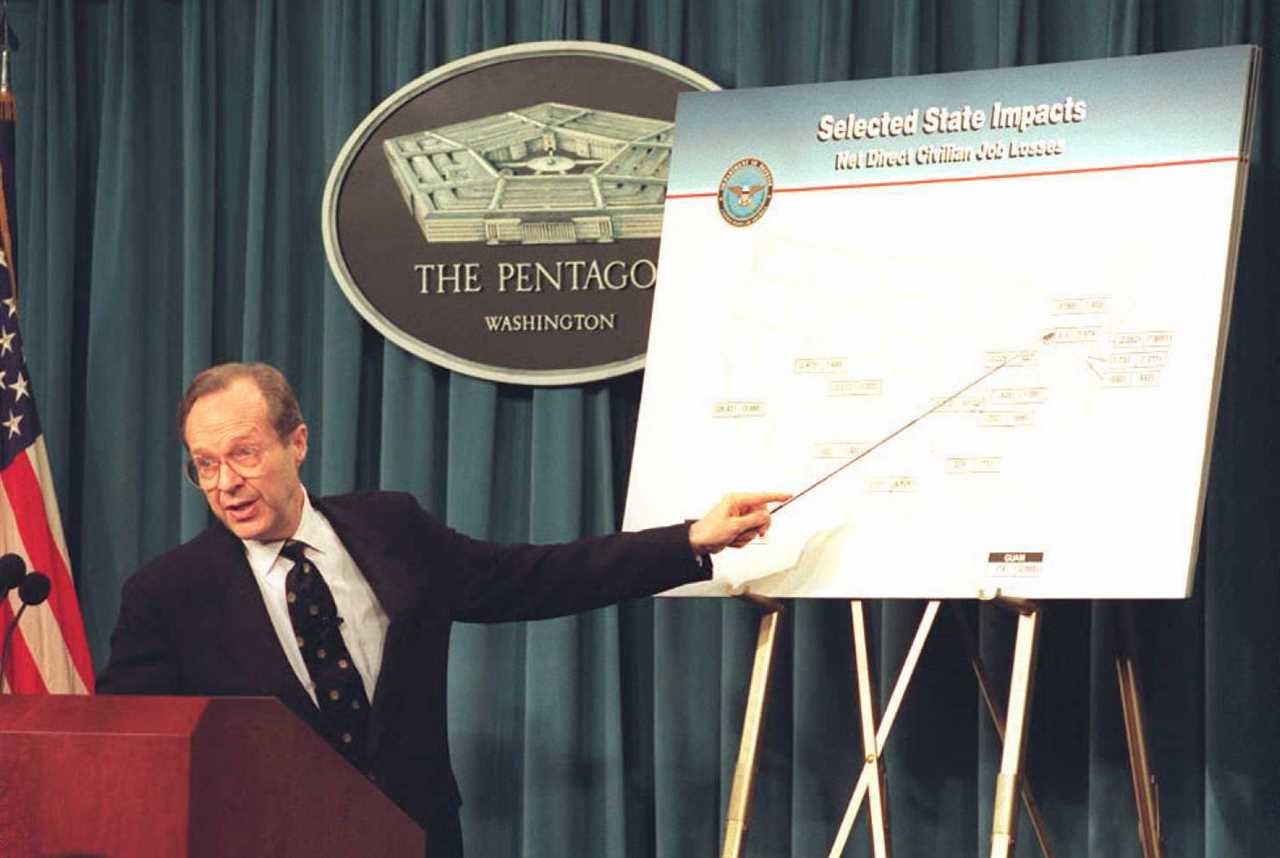

All this became clear to mandarins of the U.S. defense industry one evening in the autumn of 1993, when then-Deputy Defense Secretary William Perry gathered about a dozen or so of them at the Pentagon. Perry fed them a nice dinner and then delivered a blunt and stomach-turning message: The fat years of the Cold War were over. The military-industrial complex was done. Defense budgets would continue to shrink dramatically and many of them would soon be out of business. “We will stand by and watch it happen,” Perry told them, adding that the defense companies should “adjust their plans accordingly.” As Perry later recounted, that meeting “precipitated a whole series of consolidations” involving mergers and industry drop-outs, as well as dependence on global supply lines that came to incorporate China, a possible future adversary.

The 1993 dinner, which became known as the Last Supper, marked a fundamental shift in mindset that shaped the course of the next 30 years. At least until 9/11, that time period was marked by ever-plummeting budgets, pell-mell departure of firms from defense contracting and, above all, complacency in the face of what seemed a serene future with no obvious strategic threat on the horizon. Even Perry, who soon after became President Bill Clinton’s defense secretary, admitted years later that the unwinding of America’s Cold War defense apparatus went much too far. Before long the industry underwent what Paul Kaminski, former under secretary of defense for procurement, called “excessive vertical integration,” dwindling to one or two monopoly suppliers for everything from large-scale weapons systems to a whole array of crucial components such as processors and sensors used in flight controls.

And after the Gulf War and the advent of the “smart bomb” era in 1991, when the Pentagon thought it could take out enemies quickly from the air, complacency spread far and wide. Both Democratic and Republican administrations pushed industry to globalize, even though Cold War-era export restrictions continue to obstruct defense technology sharing. Defense spending dropped from 5.2 percent of GDP in 1990 to 3.0 percent in 2000, according to the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

Today the Pentagon suddenly finds itself scrambling to re-weaponize across the board — from submarines to aircraft to surface-to-air missiles — as Washington awakens to the reality of twin strategic threats from China and Russia. That may seem surprising at a time when the Pentagon still commands an $858 billion budget that exceeds the discretionary spending of every other federal agency put together, and which is almost twice as high as in the late ‘90s. Biden’s $886 billion request for 2024 would put the defense budget “at one of the highest levels in absolute terms since World War II — far higher than the peaks of the Korean or Vietnam wars or the peak of the Cold War,” said William Hartung, a military budget expert at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. “And the U.S. spends more than the next 10 countries in the world combined, most of whom are U.S. allies, including about three times what China spends.”

But this is in part because of the 20-year-long “war on terror,” in which the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan and the huge expenses of occupation, counterinsurgency and counterterrorism sucked up so much in resources and attention, with the Pentagon spending nearly $14 trillion in response to 9/11, according to the Costs of War project at Brown University. Added to this was the huge cost of caring for the post-9/11 war veterans. (As a percentage of GDP the 2023 budget was still just over 3 percent but this was largely due to the rapid growth of the economy.)

“The 20 years post 9/11 really ought to be acknowledged as the era of the Great Distraction,” says retired Air Force Lt. Gen. David Deptula. “We got too distracted from the real threats posed by China and Russia.”

Hartung, who helped compile the Costs of War estimate, said such claims are “overblown” since the Defense Department had ample funds to spend on weapons modernization over the past decade as those wars wound down. The direct costs of war in Afghanistan and Iraq were probably less than a quarter of that $14 trillion, Hartung said. A bigger problem was inefficiency and waste: A lot of money continued to go to antiquated weapons systems that the Pentagon sought to retire but members of Congress wanted to maintain because they were produced in their districts or states. Hartung and other Pentagon critics say the five remaining major weapons contractors — Lockheed Martin, Boeing, General Dynamics, Raytheon, and Northrop Grumman — have also squandered billions on stock buybacks and bloated executive compensation.

Muddling things further is that Congress remains confused about what needs to be prioritized, and “right now there isn’t a consistent demand signal from the DoD to industry,” said CNAS’s Wasser. The problem is not partisanship, she said, since “the China challenge is one of the rare areas of agreement on Capitol Hill these days,” but rather “how Congress and the Pentagon communicate with each other.”

Thus the Ukraine drain has only exacerbated what one defense analyst, Mackenzie Eaglen, has called the “terrible 20s,” the effect of congressional squabbling that delayed weapons modernization bills has left the military with “aged chassis, hulls, and airframes that cannot be upgraded with today’s technology and cannot generate the kind of power needed to survive any fight.” These include Eisenhower-era B-52s and Minuteman missiles that have exceeded their shelf life.

“It’s a horror story,” Eaglen said in an interview. “We can’t put any more Band-Aids on a defense industrial base that has reacted to government signals for the past three decades and is now purely a peacetime industrial base. There is no more ‘Freedom’s Forge’ or ‘Arsenal of Democracy.’”

Indeed, the Ukraine invasion has signaled the start of a new era of industrial warfare, in which Washington may have begun to cut into its own deterrence posture by delivering more than 10,000 Javelin anti-armor missiles and Stinger anti-aircraft missiles to Ukraine (though many of these munitions would not likely be used in a war with China).

“We haven’t fired munitions at this rate since World War II,” said the Senate defense expert who spoke on condition of anonymity. “And air defense was not something we had to worry about for 20 years in Iraq and Afghanistan, so we sort of took our eye off the ball.”

The main goal against China, experts say, should be not to fight a war but to deter Beijing from starting one. Yet questions remain whether the Biden administration has fully grasped the scale of the problem.

“They came to power not wanting to deal with these issues,” says Bill Greenwalt, an expert in the defense industrial base at the American Enterprise Institute. “Now they’re starting to get mugged by reality in a sense.” The Senate expert on the Democratic side agreed that “the sense of urgency is nowhere near what it should be. … Many don’t yet see this as an existential threat. There are some people who think we’re crying wolf.”

Some critics make the case that the strategic threat is exaggerated: China’s economy is suffering record low growth, and the Biden administration has barred it from getting advanced computer chips that Beijing can’t make on its own. Russia seems hopelessly bogged down in Ukraine. The administration also argues that it has moved quickly in some key areas that shore up deterrence. It is negotiating new agreements with Pacific allies, especially the AUKUS pact between the U.S., Britain and Australia, which will see four U.S. Virginia-class submarines (state-of-the-art attack subs) and one U.K. Astute-class submarine begin deployments to Australia in 2027. It has gained access to several bases in the Philippines. The administration has also embraced defense-related industrial policy, with a $52.7 billion investment in domestic semiconductor manufacturing.

Mark Cancian of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, who produced a report on one of the wargames in January called “The First Battle of the Next War,” said that while the proposed defense budget through fiscal 2024 is not enough to make a difference, the administration’s “Future Years Defense Plans” stretching out to 2027 could mean that increased munitions production will suffice as a Band-Aid. Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks, who is running the modernization program, said she is expediting the FYDPs to address the Taiwan threat.

Under the Biden administration, there has also been serious pushback by the Federal Trade Commission toward defense industry mergers for the first time in recent history. In 2022 the FTC sued to block Lockheed Martin’s $4.4 billion acquisition of engine-maker Aerojet Rocketdyne. But consolidation is still outpacing government efforts, especially when it comes to big-name contractors buying up smaller, less visible suppliers. And there is little or no cooperation across government agencies to prevent that. It also took the Biden administration until March of this year to put in place an assistant defense secretary for industrial policy, Laura Taylor-Kale.

Yet another problem is the long lead time for planning, development and manufacture, as the handful of major contractors left, such as Lockheed Martin and Raytheon Technologies, await multi-year contracts under an antiquated acquisition process dating from the early Cold War. They are also demanding reform of just-in-time inventories, another post-Cold War efficiency measure that prevents a buildup of reserve capacity.

“If you knew that we had to defend Taiwan in three years, then we’re already two years too late,” says Heather Penney, a former Air National Guard pilot and senior fellow at the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies. “It takes two years to budget for these platforms, a year to set up supply, a third year to put all that together, and it takes roughly five years to produce an experienced combat pilot.”

Beyond that, although the U.S. has always considered itself a Pacific power, Taiwan is literally in China’s backyard and Beijing considers ownership of it a vital national interest. “The most important thing to remember is that China is fighting a home game in that region where the U.S. is fighting an away game, so we have to bring much more mass to bear,” says Wasser. “Attrition is baked into Chinese assumptions.”

Politicians and generals are always fighting the last war and often forgetting the lessons. Or at least misunderstanding them.

Americans have always seen ourselves as the “arsenal of democracy,” and history tends to glorify the rapid build-up of America’s World War II military in only a few years. We did it once, the thinking goes, against two formidable foes at the same time, Germany and Japan — so why would it be so hard for the most technologically advanced nation on earth to achieve the same thing against China and Russia?

But in truth the changeover from peacetime to a wartime footing then took longer than most people think. Through the 1930s, especially as the Japanese ravaged Asia, prescient congressmembers such as Carl Vinson of Georgia pushed through legislation for a bigger navy — and got one. By the time war came, the entire allied effort depended on “the immense shipbuilding program of the United States,” then-U.K. Prime Minister Winston Churchill said in 1942. Even coming out of the Great Depression, there was a strong U.S. manufacturing base across the board from major automakers to mom-and-pop toolmakers.

“We lack that today,” says Penney. “Unlike World War II, America no longer has the skilled manufacturing base to spin up and support wartime production.”

Another obstacle is that the mindset of a later conflict, the Cold War, still dominates Pentagon acquisition policy. The so-called “planning, programming, budgeting and execution” (PPBE) system still drives contracting. But it was designed more than a half century ago for the much slower defense buildup of the Cold War and is clogged with bureaucracy. “We were competing then against a system of five-year planning by the USSR,” says Greenwalt. “In effect we became the Soviet Union when we adopted this process.”

In 2021 former Google CEO Eric Schmidt called the PPBE system an “outdated, industrial-age budgeting process” that “creates a valley of death for new technology … preventing the flexible investment needed in prototypes, concepts, and experimentation of new concepts and technologies like AI.” Senate Armed Services Chair Reed calls the PPBE process “one of those relics of days gone by.” One casualty of the PPBE process was the Pentagon’s failed attempt to build a cloud computing system, JEDI, after long delays in contract procurement.

Currently a 14-member Commission on Planning, Programming, Budgeting and Execution Reform is looking at ways to change the 61-year-old system, which requires corporate strategists to plan for new programs long before getting funding, allowing commercial technology and modernization to surge ahead of government efforts. But critics say the lead must come from the Pentagon, which is the only entity that can push real change and shift priorities for industry.

“The DoD is a monopsony; the U.S. government is the only buyer,” says Jones. “So if the Pentagon sends out a demand signal that they are prepared to buy these kinds of systems on a significant scale, industry will commit.”

Gallagher, chair of the Select Committee, agrees with that assessment. While the industrial base needs a longer fix, he believes the munitions gap in East Asia could be addressed in the next several years if the Pentagon swiftly makes fresh demands of industry. “The most obvious concern is we don’t have any long-range munitions deployed west of the international dateline,” he said. But he points to what former Defense Secretaries Robert Gates and Ashton Carter did when U.S. troops were being killed and maimed in large numbers by IEDs in Iraq and Afghanistan, prioritizing production of the Mine Resistant Ambush Protected vehicle, or MRAP. Gallagher believes that at the very least the Pentagon could “MacGyver” — that is, force a quick turnaround on production lines — to supply hundreds of long-range Harpoon missiles to the Taiwanese military.

“Maybe I’m an optimist, but you’ve got to be an optimist when it comes to preventing World War III,” says Gallagher.

What is clear is that should war come, it may already be too late to match China ship-for-ship, and plane-for-plane.

The Biden administration has made some efforts to change this. Under the 2018 National Defense Authorization Act, Congress required the Navy to increase the number of its combat ships to 355 (from fewer than 300 now) “as soon as practicable.” But the DoD’s building plans don’t make that feasible for decades, perhaps until the 2050s. Meanwhile, under China’s more autocratic, less bureaucratic system, the People’s Liberation Army Navy passed the U.S. Navy in fleet size around 2020, now has around 340 warships and is expected to grow to 400 ships by 2025, according to the Pentagon’s 2022 China Military Power Report. The U.S. is currently building only 1.2 subs a year (despite a congressional requirement for two a year), and Biden’s fiscal 2024 budget calls for building only nine new battle force ships.

So now may be the time for a radical shift in defense thinking. First, this would mean de-emphasizing traditional platforms like expensive, and newly vulnerable, aircraft carriers and moving to exploit the best of U.S. high tech advantages, including the most recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence that American industry dominates and which could power new generations of drone aircraft and ships.

“The only way we win is by radically scaling our investments in non-traditional military capabilities, such as lower-cost autonomous systems,” says Brose, who is chief strategy officer at a company that makes such systems, Anduril Industries.

This is just beginning to happen. Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall, for example, is leading the development of “collaborative combat aircraft” under which a thousand or more drone “wingmen” operate alongside a much smaller number of piloted planes, part of a program called Next Generation Air Dominance. In early April, Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro announced the service is ready to expand the use of unmanned systems to the broader fleet. But in other areas change is glacial: The Navy just suspended its own “Snakehead” project which would have built smaller, underwater autonomous vehicles because budget money wasn’t available for the next-generation submarines that could carry and launch the Snakeheads.

Kendall recently urged Congress to give the military the authority to start new developmental programs before a budget is approved. “Time is going by, and all those things that we worked hard to understand and formulate good solutions to, we’re not able to act on them yet,” Kendall said at the Space Symposium in Colorado Springs, Colo., on April 19. “That’s a lot to give away to an adversary when it’s totally unnecessary.”

Frank Calvelli, assistant secretary of the Air Force for space acquisition and integration, is pushing the U.S. Space Force to move from buying billion-dollar satellites that on average take seven years to develop to building smaller and more expendable ones in three years. Calvelli said that big satellites aren’t needed for most war planning and only make “big juicy targets.” “Our competitors seem to have figured out speed. It’s time we do the same,” Calvelli said, referring to China.

Another partial solution is to accelerate co-production with allies such as Australia — in effect pooling industrial bases. China may dominate shipbuilding for example, but Nos. 2 and 3 in the field are South Korea and Japan, both close U.S. allies. But here as well too much of the antiquated Cold War-era structure remains: Congress must act to update two sets of regulations — the International Traffic in Arms Regulations and the Export Administration Regulations — which make it nearly impossible to share dual-use technologies even with friendly countries.

Even now, LaPlante conceded, “AUKUS will not work if we don’t have the data sharing piece worked out.”

If the United States can’t manage to shore up its conventional deterrent through such means — rapid modernization, co-production and expedited munitions — then it may have to rely on a third option, by far the most frightening one: its nuclear deterrent. This is what happened during the last major Taiwan crisis of the Cold War, in 1958, when U.S. generals threatened nuclear strikes on mainland China that would have left millions dead, according to classified documents revealed by Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg in 2021.

Today, as tensions rise between the major nuclear powers, brinkmanship has again become a possibility, says CSIS’s Jones. Among major U.S. allies such as Japan and Korea, it has also led to discussions about whether they should develop nuclear arsenals if the U.S. fails to beef up its conventional deterrent sufficiently in the Indo-Pacific. “We are in an era when we have the prospect of direct war between nuclear powers close to their home territories. This is mainly what is driving tensions,” says Jones.

After Pearl Harbor, Japanese Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto was famously said to have warned (though the quote is apocryphal) that he thought all Japan had achieved with the surprise attack was to “awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve.” That is pretty much what happened, and the United States utterly destroyed Japan’s military machine.

But now, says Jones, the giant is “lying in bed still. Its eyes are open and it’s recognizing there’s a problem. But it’s got to get out of bed.”

----------------------------------------

By: Michael Hirsh

Title: America Is Running Low on Weapons. China Is Watching.

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2023/06/09/america-weapons-china-00100373

Published Date: Fri, 09 Jun 2023 03:30:00 EST