Why is life in this country so hostile to single people?

Think about your household’s monthly expenses. There are the big-ticket items — your rent or mortgage, your health care, maybe a student loan. Then there’s the smaller stuff: the utility bills; the internet and phone bills; Netflix, Hulu, and all your other streaming subscriptions. If you drive a car, there’s gas and insurance. If you take the subway, there’s a public transit pass. You pay for food, and household items like toilet paper and garbage bags and lightbulbs. You buy furniture and sheets and dishes.

Now imagine paying for all those things completely on your own.

If you live by yourself — or as a single parent or caregiver — you don’t have to imagine. This is your life. All the expenses of existing in society, on one set of shoulders. For the more than 40 million people who live in this kind of single-income household, it’s also become increasingly untenable. When we talk about all the ways it’s become harder and harder for people to find solid financial footing in the middle class, we have to talk about how our society is still set up in a way that makes it much easier for single people to fall through the cracks.

First, we need to define a clunky but essential term. Single or solo-living people may or may not be partnered with someone in the long or short term, and they may or may not be parents, but they all live and bear the responsibility for their bills alone. Some are retired; some are widowed or divorced; some are in long-distance relationships that require two households. Some have lived alone, purposely or regretfully, their entire lives.

There are so many routes to and reasons for arriving at the single or solo-living life, and more people are living it than ever before: As of 2021, 28 percent of Americans live alone. Back in 1960, it was just 13 percent; by 1980, it was 23 percent. An additional 11 million households are headed by a single parent, a number that has tripled since 1965. Overall, 31 percent of US adults identify today as single, defined as not married, living with a partner, or in a committed relationship.

The 31 percent figure holds true for both men and women in the aggregate but varies significantly by race and sexual orientation: According to Pew’s most recent survey data, 47 percent of Black adults are single, compared to 28 percent of white adults and 27 percent of Hispanic adults; 47 percent of adults who identified as gay, lesbian, or bisexual are single, compared to 29 percent of straight adults.

Then there’s the age breakdown: Women live significantly longer — and, over their lifetimes, make less money. Men, as a general rule, are far more likely to be single when they’re young, marry later (or for a second time), and stay married until their deaths. The reverse is true for women: They’re more likely to marry young but then end up divorced or widowed and living alone as they age. Given these and other trends — including the high cost of aging, the fact that women (and Black women in particular) make significantly less money over their lifetimes — it is women (and again, Black women in particular) who often bear the biggest financial load of single life.

You can attribute some of these increases to no-fault divorce, which began to standardize in the 1970s; the continued aging of boomers — who are growing old but not always together; and college-educated people, in particular, delaying marriage until later in life. Add in the sexual revolution, the feminist movement, the mass incarceration of Black men, the inability for same-sex couples to marry one another or, in some states, safely cohabitate until relatively recently, and declining rates of religious observance, and you have a whole slew of intersecting reasons people are single or solo-living at far greater rates than ever before.

To be clear, these numbers aren’t increasing because society has shifted to accommodate the single or solo-living. Quite the contrary; they are increasing even though the United States is still organized, in pretty much every way, to accommodate and facilitate the lives of partnered and cohabitating people, particularly married people. We don’t seem to like or respect single people and their choices. It doesn’t matter how many songs or books or movies seem to champion the triumphs of the single person. Our societal actions — the way we support and reward people — suggest otherwise.

Single people should, in theory, be the purest embodiment of American values of self-sufficiency and individualism. That they’re not speaks to the fact that we don’t venerate the individual — we venerate the individual family. The family fosters the conditions for the individual’s success: The spouse helps create the conditions that make success possible; children (at least theoretically) keep the individual grounded, focused, and humble. Which is why so many narratives of “individual” success either start with that family already firmly in place or — as is the case with so many rom-coms and memoirs, from Sex in the City to How to Be Single — end there.

The celebrated single life is, in truth, incredibly narrow. For women, you have to be 1) actively and successfully in search of partnership; 2) unspeakably wealthy and above scrutiny; and/or 3) a self-sacrificing mother. “Confirmed” bachelors can sometimes get a pass so long as they don’t move back in with their parents; so do the elderly, the widowed (but only for a brief window of time), and the very young. Other single and solo-living people are still stigmatized in various and overlapping ways, depending on their age, class, race, and sexual identity. We don’t call single or unmarried people spinsters, deviants, or social problems anymore, at least not explicitly. But that underlying hostility to single and solo-living people? It’s everywhere.

This was the difficulty for me when I revisited Rebecca Traister’s All the Single Ladies in preparation for this article. The book, chock-full of stories of how women have carved successful and meaningful unpartnered lives for themselves, includes a clear-eyed look at the costs of exclusion. Yet it is still an advertisement, of sorts, for a way of life. Reading it, as I did, after combing through the stories of women who’d written to me about the small and insurmountable barriers to stability, made me realize just how much we’ve learned to excuse. Just because single people have managed to survive — and even thrive — in the face of societal hostility does not mean they have not suffered enduring consequences or that others do not suffer them today.

In the fall of 2019, 28-year-old Amelia was splitting a two-bedroom apartment with a friend in Los Angeles. Like a lot of people, she needed a roommate to drive down costs, but having a roommate is not a cure-all for the instability of single life: People move out, sometimes to live with partners or on their own. For many, living with a roommate means always waiting for your situation to change, without your say, when the lease comes up. Amelia was getting by, but she could never save up to pay off her credit card bills or pay down her student loans, let alone build an emergency fund. (Amelia, like the other people I spoke to for this story, is being referred to by first name only to protect her privacy around personal finances.)

Then she lost her job, and after four months of searching without success, she had no other option than to move back into her parents’ home in Las Vegas. She eventually found a “white-collar knowledge industry job” that she could do remotely and watched as her financial footing got more solid with each month.

Nearly two years later, Amelia has paid off several of her student loans and her car loan, amassed an emergency fund, and saved enough for a small down payment on a house. You could say that’s because she was no longer paying rent. Part of it, though, was just living with her parents: She rotated paying for groceries, borrowed their car when hers needed repair, and didn’t have to go further into credit card debt while she continued to look for a job. She had a glimpse, in other words, of what it might be like to share financial responsibilities with a partner, not just split utilities and rent with a roommate.

Now that Amelia’s moving out on her own, though, the costs of living alone will start to show up, like quiet guests arriving through the back door at a party. You don’t even realize how much work you’re doing to host them until you look at the house across the street and see that they have the same number of guests, but there are two hosts working in concert to handle all the tasks and cover all the costs.

That’s kind of the reverse of what happened to Rachel, 37, when she and her husband divorced three years ago. “If anything will throw your basic beliefs about the nuclear family and the partnered American dream out the window,” Rachel told me, “it’s an emotionally devastating breakup coinciding with the birth of your child.”

Shortly after the divorce, Rachel’s brother told her that the house next door to him was about to go up for sale. The rents in Bellingham, the midsize Washington state college town where they both lived, were becoming more unsustainable every year. Soon, buying a house on her public school teacher salary — which, with nine years of experience, plus a bonus for teaching in a Title I School, adds up to around $100,000 a year — might be out of reach. So Rachel did something impulsive: She cashed out the entirety of her IRA, borrowed some money from her parents and her ex-husband, and bought the house, which she shares with her 5-year-old son.

Something else lives there, too: “the giant, scary beast” that is her mortgage payment. “I can make it month to month, but any sort of savings or emergency fund is very off the table,” Rachel explained. “That’s the huge difference between being partnered and being solo: the ability to build savings. And I feel like if an emergency happened, there would be some sort of safety net.” There’s an oft-cited stat that only 39 percent of Americans think they could cover a $1,000 emergency expense — but a 2018 Federal Reserve study showed that just 15 percent of single parents had three months of expenses on hand, and 40 percent didn’t have more than $400 in savings.

In many ways, Amelia and Rachel are privileged in the single world. Both have managed to buy their own homes — even if, in Rachel’s case, it also meant mortgaging some of her retirement. For many of the hundreds of people I heard from during my reporting, cobbling together enough for a down payment, let alone qualifying for a mortgage on a single income, feels impossible. Same, too, for having kids on one’s own or going through the process to adopt.

Caitlin, who’s 33 and lives in the Washington, DC, area, is asexual and aromantic and is not looking to be partnered. She could get a roommate, which might help with some monthly bills, but between DC’s high cost of living and the student loans she’s only recently been able to get below six figures, it would still take her years to save up enough for a down payment. As she put it, “not being able to save much, or even just depending on the savings of one person, means that homebuying and having kids are just a fantasy.” And that’s on a pre-tax salary of around $100,000 a year.

Caroline, who’s 46, lives in Vermont and has been in a relationship with someone for 10 years. A number of factors, including logistics and jobs and divorces, have meant that they’ve never been able to live together, and she’s not sure that she’d want to. Yet “life is so freaking expensive,” she said. “With two people contributing, perhaps you could actually take a vacation. I could probably pay for things like haircuts, or new clothes, without going into debt. And, of course, the finances are only half of the story: There’s also the cost of time and energy. Whether it’s time spent on the phone to find someone to fix the roof, the energy it takes to plan a college tour for my kid, or the stress of the heating bill, having someone to share that with would be nearly invaluable.”

These issues aren’t just about personal attitudes: American society is structurally antagonistic toward single and solo-living people. Some of this isn’t deliberate, as households cost a baseline amount of money to maintain, and that amount is lessened when the burden is shared by more than one person. There are other forms of antagonism, too, deeply embedded in the infrastructure of everyday life. Even as more couples than ever “cohabitate” without being married, so many of the structural privileges of partnership still revolve around the institution of marriage. (The US Census still conceives of the status of “single” as anyone who is not, at present, married.)

First, there’s the tax code. Most people don’t realize that until 1948, everyone filed income taxes alone, regardless of marital status. The policy changed in the hopes of discouraging “income shifting,” in which, say, a husband who was making $100,000 would transfer $50,000 of that money to their wife, ensuring that both of them were taxed at a lower rate. (This period was also, it should be noted, when the income tax rate for top earners was between 80 and 90 percent.) “Joint” filing was created as a means of replacing income shifting with income splitting.

The scenario was pretty great for married people, particularly married people with one income. For single people? Less great. As legal scholar Anne L. Alstott argues in “Updating the Welfare State: Marriage, the Income Tax, and Social Security in the Age of Individualism,” the vast majority of adults at the time were either married or planning to get married. (The median age of first marriage in 1950: 23 for men, 20 for women, with 78 percent of adults married, and many of the unmarried widowed.) Who would protest?

By the end of the 1960s, that foundational assumption of the tax code began to falter. Divorce rates were slowly climbing, and more and more women were entering the workforce. Congress decided to modify the tax brackets so that joint filers wouldn’t have quite as large a tax benefit. That modification created its own problem: the so-called “marriage penalty” for couples where both spouses were working for pay outside the home, which often pushed them into a higher tax bracket than if they were filing as single people.

The marriage penalty has faded in recent years, particularly after the 2017 Republican tax cuts that targeted high incomes. But the singles penalty remains — the tax code is still written to benefit people in 1950s middle-class marriages who own their homes. That’s not great for the millions of households who are shouldering other cost burdens around single life.

Progressive tax codes are intended, at least theoretically, to ensure equitable distribution of the costs of maintaining civilization. They should (again, theoretically) be readjusted when a certain group begins to shoulder a disproportionate amount of that burden — like, for instance, single or divorced people. That’s not what’s happened, not for couples with two earners and not for the growing number of single or solo households. The reality of how people live and who works has changed. The policy has not kept pace.

The same principle holds true for Social Security, which was created first and foremost as a means of protecting the elderly from living out their final years in the literal poorhouse. The idea was simple: You and your employers pay in part of your salary now, and when you retire, you have enough to survive.

The architects of the program were aware that it would only work if you also created a means for women who never worked for pay (housewives), those whose paid work was ineligible for Social Security (domestic workers), and those whose work was intermittent and always paid less than men’s to have access to their husband’s benefits, either as partners in retirement or in case of death or disability. They needed a system that acknowledged the patriarchal formation both of the home and of paid work. So they offered women who reached Social Security age a choice: You can claim your own benefits, which are probably paltry or nonexistent; you can claim a “half” benefit as a spouse; or, if your husband dies, you can claim full “survivor’s” benefits.

But what happened to divorced women? Initially, if you’d been married for 20 years before divorcing, you could still claim that half benefit. When more and more people started getting divorced, Congress reduced the minimum marriage length to 10 years. That was a useful corrective, but it still limits the “better” benefit — that is, the ability to access a man’s benefit, which, given the enduring wage gap, is almost always higher — to people who are men, or who are or were married to men for a significant period.

Between 1990 and 2009, for example, the number of women who reached retirement age without claim to a man’s benefits increased from 7.5 percent to 16.2 percent; for Black women, it went from 13.4 percent to 33.9 percent. To be clear, most of these women did have benefits of their own, but the pay gap and the fact that women are far more likely to work in “feminized” fields with lower pay mean they almost certainly received less than a man in their demographic would have. In 2019, the average overall benefit for a retired man was $1,671 a month, compared to $1,337 for a woman. A divorced woman’s benefit would likely still be larger than the half benefit she’d receive from her ex-husband, but a widowed woman’s whole “survivor” benefit would presumably be higher than her own, especially if she took any time out of the workforce to care for children or elders.

All of this is complicated and something that most people don’t think about until they start to near retirement age (or their parents do). It matters because it again underlines the structure of American life that’s prioritized and favored. It’s not that Social Security necessarily penalizes people who are single. In fact, it has been modified several times to account for the newly single. The problem, then, is that it’s still organized around the understanding that American women will get and stay married to a man at some point in their lives, even as that understanding has ceased to hold true for millions.

As Suzanne Kahn notes in Divorce, American Style: Fighting for Women’s Economic Citizenship in the Neoliberal Era, other public safety net programs — and private ones intended to supplement them — were built in the same model. Pensions, health insurance benefits, IRAs: All of them are organized to best accommodate the needs of married (or widowed) family units. If you’re married, you can be added to a spouse’s insurance policy, which allows spouses to drop in and out of the workforce as needed or seek out jobs that don’t provide full-time insurance. Single people, particularly single people with chronic health conditions, have fewer options, even after the rollout of Obamacare. (In many states, the available options on the marketplace exchange remain prohibitively expensive.)

Then there’s the sheer amount of benefits conferred by many workplaces to people who have children. Parental leave is fantastic. We should have more of it. But there should also be forms of leave, caregiving or not, for people who choose not to have children. The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) allows people to take unpaid time off to care for a family member, but it does not allow people to take time off to care for someone who is not legally family and, just as importantly, does not allow someone to take time off to care for themselves. (Expanded family leave protections have gone in and out of the Build Back Better social spending legislation that’s moving through Congress; the current proposal would expand leave to include family by “blood or affinity.”)

These policies and programs were created to decrease suffering, to lessen the effects of catastrophe (or pandemic), to protect people from descending into poverty. Yet in too many cases, they are built in a way that suggests that single or solo-living people are expected to be, provide, or pay for their own safety nets.

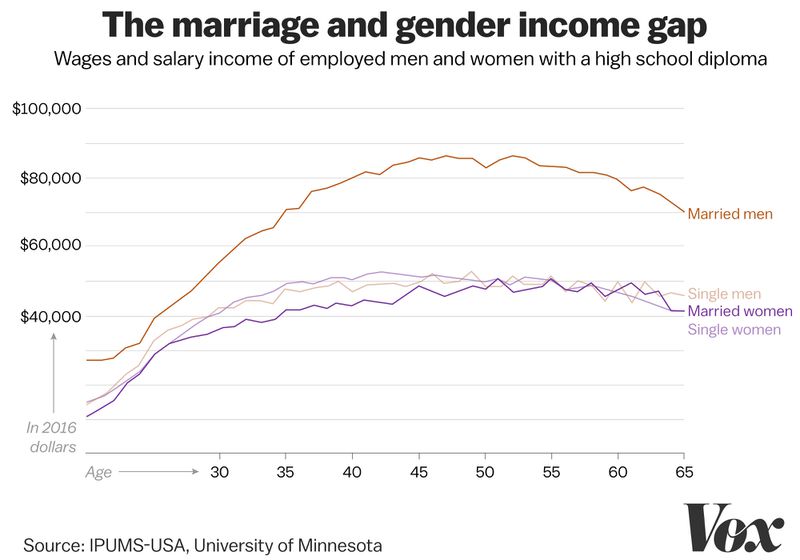

Back in 2013, Lisa Arnold and Christina Campbell persuasively laid out the high costs of being single in the Atlantic. Using various calculations based on cost of living, health care, taxes, and savings, they calculated that an unmarried person, making around $40,000 in 2010, could pay $1 million more for services over their lifetimes than married people. That’s a very expensive life choice. If that number is hard to believe, a chart of the wage and salary income of married versus unmarried people might be useful.

Christina Animashaun/Vox

Do married men earn more because they’re married? Or do people who earn more get married more often? That’s a difficult question, but it’s worthwhile to parse who, exactly, is getting married and staying that way. As I wrote last month, there’s a popular conception that the divorce rate is actually decreasing (from a high of 22.6 percent in 1980 to 14.9 percent today).

While this statistic is true in the aggregate, it obscures significant trends, particularly with education levels. (Among other factors: Same-sex marriage has not been legal long enough to directly compare broader trends.) A 2015 Pew report estimated that women with a bachelor’s degree have a 78 percent chance of their marriage lasting 20 years or longer; for women with some college, the number drops to 48 percent, and 40 percent for women who’ve completed high school or less.

While divorce trends have decreased for people with a college degree, they decreased, leveled off, and then began rising again in the 1990s for people without one. The more education you have, the more likely you are to make more money; the more money you make, the more likely you are to be able to patch over some of the potholes that can doom a marriage. In 2015, 25 percent of low-income adults between the ages of 18 and 55 were married, compared with 39 percent of lower-middle-class adults and 56 percent of families making above median income.

And then there are the thousands of people who would like to be married but can’t afford to be because additional income from a spouse would result in taking away the disability, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or child support benefits that make life sustainable. For them, marriage might be financially stabilizing down the line but not stabilizing enough to make up for the loss of other safety nets in the short term.

Marriage is stabilizing, then, but largely for people who are already stable or on the route to it. It’s become a tool of class reproduction, benefiting those who’ve always benefited within the American class hierarchy: financially stable white men and the women married to them.

The current situation is an example of economist Jacob Hacker’s theory of “policy drift,” in which situations that policy was created to serve have changed significantly but the policy itself has failed to adapt, expand, or respond to that new reality. Alstott, the legal scholar, describes this gap as one between “legal fiction” and “social reality”: one that “undermines the ability of the tax-and-transfer system to achieve any of a range of objectives, whether fostering individual freedom, aiding the poor, or shoring up the traditional family.” Put differently, our designs no longer do what they were intended to do.

The refusal to build a real safety net for people who aren’t partnered means that some people may feel pressure to do anything to be and stay partnered, even if it means enduring psychological or physical abuse. It also means that single people deal with all the same things that anyone without a safety net deals with: They often stay in bad jobs, they take fewer entrepreneurial risks, they’re less likely to follow opportunities that people with a spousal safety net could. They simply don’t have the stability that makes it not just possible but also conceivable to do so much else. It seems clear, if we want to actually support “liberty” or lift people out of poverty, or even make it easier for people to have traditional (or nontraditional!) families, then we need to reconsider the way we organize tax policy and public benefits.

Some single people love being single; some are fairly ambivalent about it; others despise it. None of those postures are made easier when your way of life is implicitly and explicitly understood as a sort of cultural and financial backwater, to be avoided at all costs. If we want to start thinking about how to make it easier for single people to find financial stability, we have to start to understand single life as something that’s not just thinkable, not just survivable, but actually desirable.

Right now, that idea is too threatening to the institution of marriage and, by extension, a pillar of the United States as we know it. The integrity of that pillar has been crumbling for years, as marriage, even with its myriad financial and cultural benefits, has ceased to prove its worth. Today, people want options for partnership that are more flexible and more like actual partnerships. You can cultivate that within a marriage, sure, but it, perhaps ironically, often takes more work than trying to figure out your own rules outside one.

Some people crave something more than what marriage can provide. They wonder: What would it look like to create small systems of care for one another that go beyond one other individual? What if we could figure out how to acknowledge that the most important person in our lives isn’t always someone bound to us by family or sexual relationship? How can we think about housing, health care, caregiving, and work in ways that actually acknowledge and actively include single and solo-living people — not as afterthoughts but as the third, if not more, of the population that they are?

There’s a whole lot that straight white single people today can learn from past and present work in queer communities, the Black Power movement, and immigrant communities — where members have long formed systems of mutual aid, many of whom were forced to come up with these systems because the existing legal and religious systems excluded them from participation. There’s also a lot to learn from other countries where single populations thrive. Denmark, for example, has offered three cycles of IVF to residents up to the age of 40 since 2007, leading to a sharp increase in “solomor” or elective single mothers.

That policy interlocks with a safety net that makes other parts of single parenting life easier: significant maternity leave, affordable and accessible day care, and universal health care. More stability means fewer of the behavioral and educational problems associated with kids who grow up in single-parent homes, the vast majority of which can be traced back not to the fact that they only had one parent but that the one parent’s finances were unstable, because of either a divorce or an unplanned pregnancy. Giving single people access to parenthood — and, just as importantly, the assurance of support once it happens, for whatever reason — could dramatically change the experience of single parenting.

Denmark isn’t perfect, and I’m always wary of holding up Scandinavian policy, simply because the paradigm shift necessary to bring the United States closer to that reality can often feel altogether out of reach. But it’s still worth thinking about what makes Denmark less hostile to single people generally. Part of it is a real feeling of community support: 95 percent of Danes feel that they could rely on someone in a time of need. But that’s also true for 91 percent of Americans. So part of it is a safety net that readily expands and contracts for all — not just the middle class, not just those in poverty, not just people who can and want to work full time, not just nondisabled or gender-conforming or straight people or partnered people, but all people, simply because they are people.

“Marriage today is no longer the primary and normal state for adult Americans,” Alstott explains in a 2013 paper for the Yale Review. “It is no longer the expected route to maturity or the exclusive site for sex, romance, and child-rearing.” It has been, in sociologists’ terms, “deinstitutionalized.” When a society fails to make policy adaptive to its new institutions — its new ways of life — it puts our fingers on the scales to favor a certain class of people. We can say we cherish single people and their contributions to society. We can yell that they are no more or less worthy of success and stability. Until policy shifts to reflect that reality, those sentiments will remain hollow.

People will continue to bemoan the erosion of the traditional family and the decline in the birthrate, because that is what people do when they feel the world is changing and they, personally, are not — maybe out of fear, but maybe, too, out of lack of imagination. We’re already a country full of people forging new institutions: of partnership, of care, of parenting. Imagine what we would look like, imagine the ways in which we’d thrive, if we decided to actually support them.

If you’d like to share with The Goods your experience as part of the hollow middle class, email [email protected] or fill out this form.

----------------------------------------

By: Anne Helen Petersen

Title: The escalating costs of being single in America

Sourced From: www.vox.com/the-goods/22788620/single-living-alone-cost

Published Date: Thu, 02 Dec 2021 13:10:00 +0000