On April 21, 1947, two rookie congressmen made their way through the bustle of Washington’s Union Station. Traveling without an entourage, they looked like any of the other business travelers rushing to catch their trains.

They hailed from different parties, different worlds really. But both had served as Navy officers in the South Pacific and had built a cordial, even friendly working relationship as the junior members of the House Committee on Education and Labor.

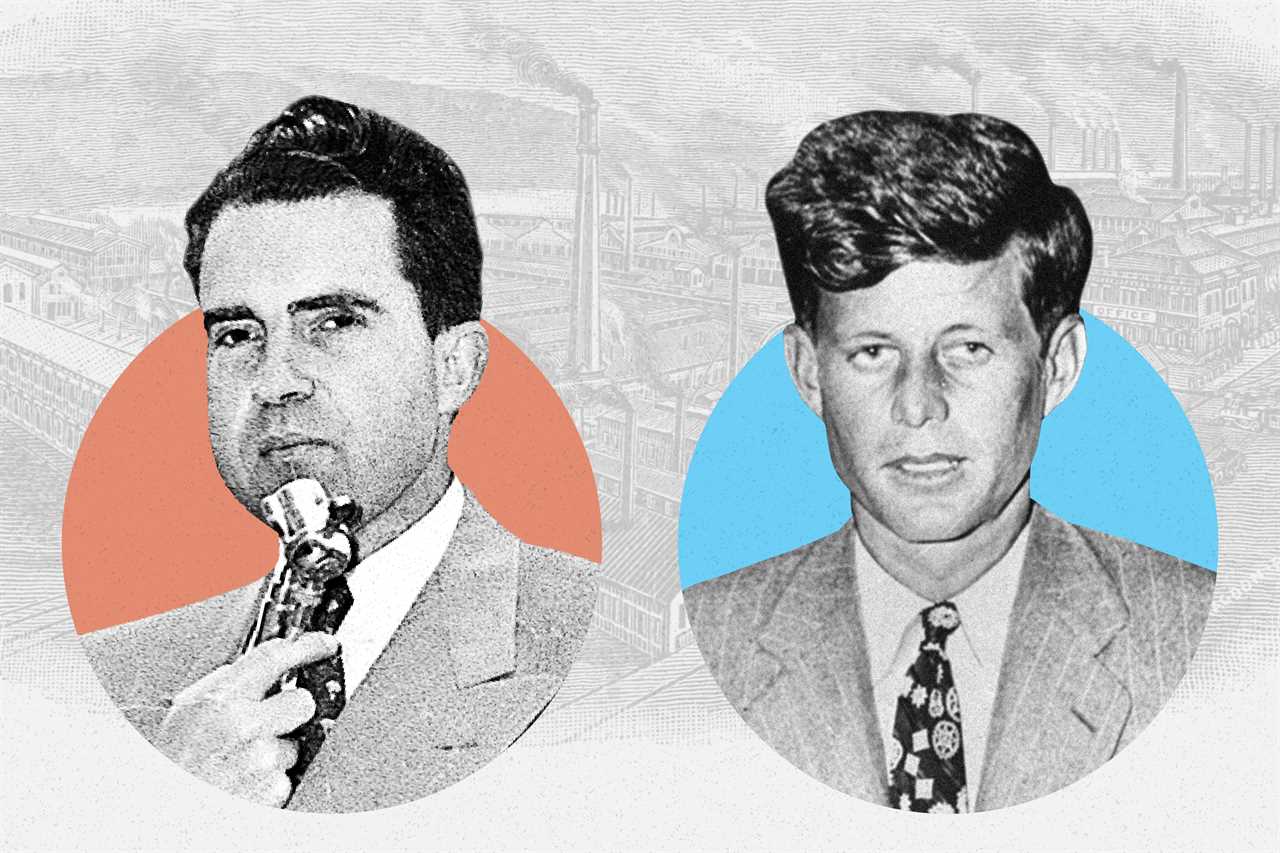

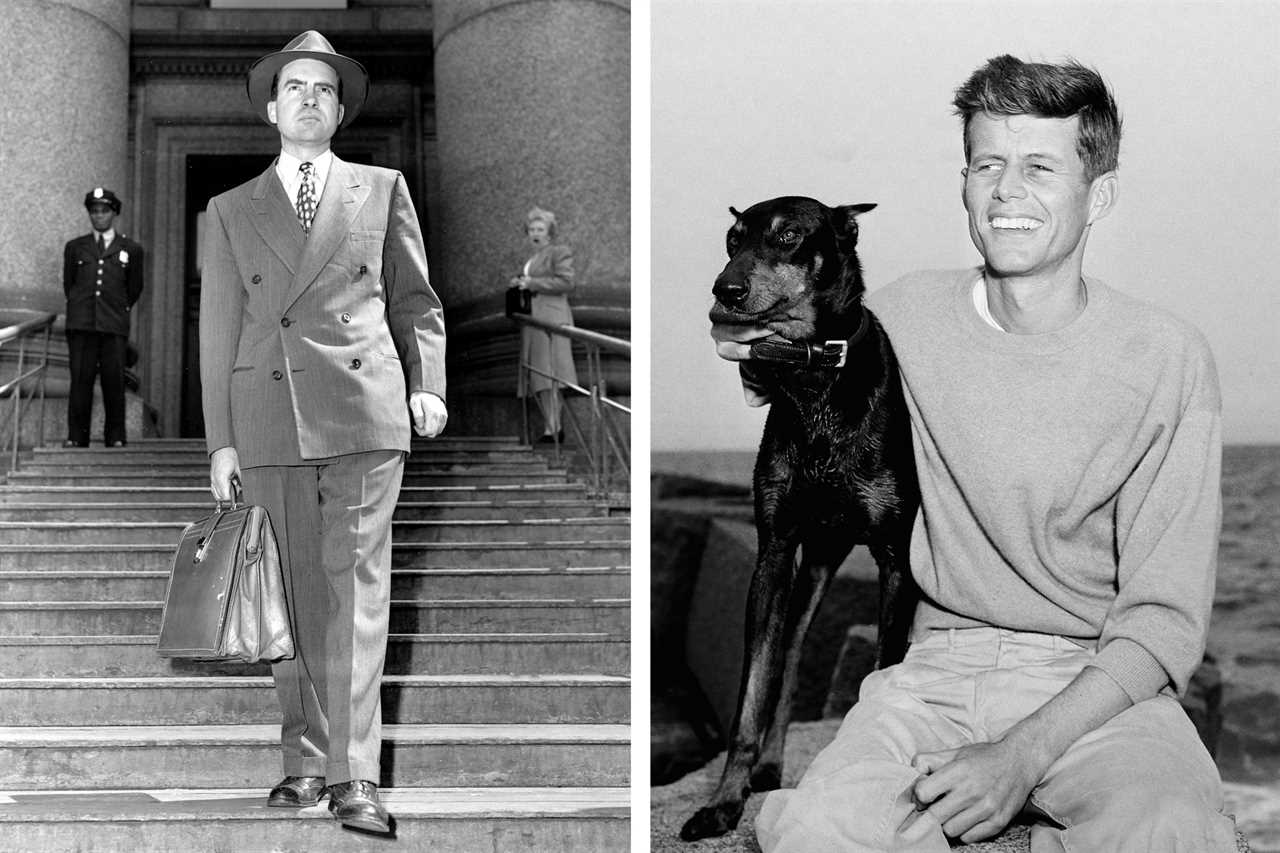

John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts, 29, still gaunt from his war injuries and numerous ailments that remained well hidden from the voters, was the boyishly handsome, devil-may-care scion of the wealthy East Coast establishment. He had been featured in a cover story in the New Yorker magazine for his war exploits a few years earlier and was elected to his seat in November 1946 without much of a fight.

His traveling companion, Richard Nixon of California, nearly five years older, was the socially awkward but ambitious product of a hardworking poor Quaker family. A Duke University Law School graduate, he had been recruited by the city fathers of rural Whittier to run against a veteran Democrat for his House seat, beating him by 14 percentage points in the Republican sweep that seized control of both houses of Congress for the first time since 1933.

The pair of freshmen had been invited by a local civic group to travel 230 miles to McKeesport, Pa., to debate one of the most hotly contested pieces of legislation that had been making its way through their committee. If nothing else, it was a chance for the two new lawmakers to raise their profiles. “We didn’t get that many invitations in those days,” Nixon would recall in an oral history interview years later, “and there was no honorarium.”

The Taft-Hartley Act, which ultimately passed over President Harry Truman’s veto, would become a signature bill of the new Republican-controlled Congress, a direct challenge to the organizing protections for blue-collar workers strengthened during President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. And nowhere was the proposed legislation more angrily received than in the industrial heartland of Western Pennsylvania, where steel mills and factories by the score employed thousands of union laborers.

Kennedy and Nixon would have some 18 hours up and back to McKeesport to get to know each other better and discuss the issues of the day. They disagreed on much, but they agreed on a great deal more, especially the emerging landscape of the Cold War, a term that had been coined only a few weeks earlier but had yet to enter the public lexicon. In the decades to come, they would each sculpt the nation’s political identity, Kennedy for his idealism and glamour and Nixon for his foreign policy achievements and more so for his cynical misuse of power.

But on that day 75 years ago this month, before they were political rivals, they were political arrivals who developed a respectful, even amicable working relationship at a time when societal and partisan divisions were raw and deep. Their first debate, 13 years before their legendary televised duels, is a fleeting and little-known chapter of American political history. It is also a reminder of a time when members of opposite parties, without teams of handlers and policy aides to run interference or shape their message, could disagree vehemently about major issues and yet still place the need to inform and persuade the public above their own political differences.

Theirs was an era that was arguably as divisive as today — riven by economic anxiety, red-baiting and overt racism. But even still, members of opposing parties could engage with each other — unscripted and in public — and not be punished by their respective leaders for fraternizing with the enemy, or risk being primaried by the ideological extremes of their respective parties for failing a purity test.

Joanne Freeman, a professor of American history at Yale University, says the McKeesport debate is nearly unthinkable in today’s hyper-partisan, social media-driven public square.

“It becomes very tricky to do anything off the cuff, anything friendly, anything that relies on mutual trust between two sides,” she told me. “All it takes is one extremist who takes advantage of it and uses it, and it is totally taken away from the two people who decided they were going to have this quiet debate.

“When the performance changes because technology changes,” she added, “then the democracy changes.”

The Journey to McKeesport

The coaches, baggage, café and mail cars lurched out of Union Station and began chugging north along the Washington to Pittsburgh route, a journey that would take them deep into the heart of the arsenal of democracy.

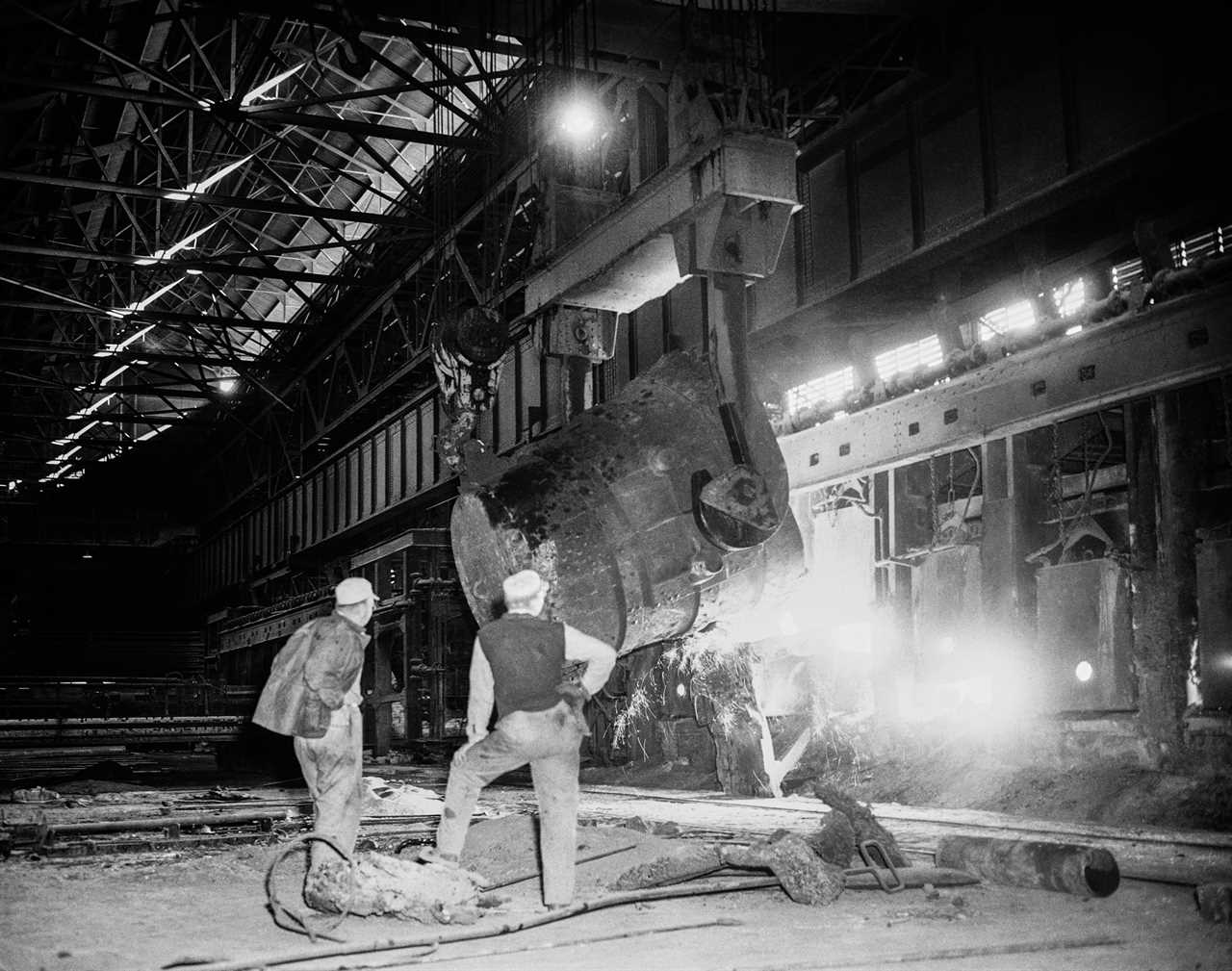

It was in Western Pennsylvania where many of the ingredients for the Allied victory over the Axis Powers had been mixed. In McKeesport, a dozen miles southeast of Pittsburgh, the machine shops and mills had help build the armored plates, structural beams, shell casings, gears, motors, drive shafts, landing craft and even PT boats like the one Kennedy skippered — as well as the freight cars and steel rails that carried them to plants and ports across the country and ultimately on to the battlefields of Europe, North Africa and Asia.

But in the nearly two years since the end of the war, the sense of common national purpose had given way to post-war uncertainty. Millions of veterans returning from the fighting sought jobs in industries that were contracting from their peak wartime production. There was violence stemming from labor unrest.

The factory floors that had fed the war effort were now battlegrounds themselves in the expanding ideological clash with the Soviet Union as management, with the eager backing of their elected representatives in Washington, strove to rid labor unions of members of the American Communist Party. Some organizations, like the Electrical Workers’ Union, which was heavily represented at the Westinghouse plant in McKeesport, were embroiled in an internal war as their leaders were being hauled before Congress and grilled about their political loyalties. Pittsburgh’s Father Charles Owen Rice, a leading anticommunist voice in the heavily Catholic region, had recently penned a handbook titled “How to De-Control Your Union of Communists.”

In Washington, Kennedy and Nixon’s committee debated whether to require every union officer to swear an oath that “he was not a member of the Communist Party nor affiliated with such party, and that he does not believe in, and is not a member of or supports any organization that believes in or teaches, the overthrow of the United States government by force or by any illegal or unconstitutional means.”

In those early debates, Kennedy came off as one of the more hawkish members. “Did you ever attend Communist meetings after the time you became a Communist?” he badgered a 22-year-old union member at a field hearing in Milwaukee a few weeks earlier. “You don’t know how many, do you? Do you know where they were held? Any secret meetings?”

New life had also been breathed into the House Committee on Un-American Activities to which Nixon was also assigned — and it was aggressively launching a campaign to root out communists from nearly every major American government, academic and cultural institution, particularly in Hollywood.

The White House was launching a broad offensive of its own. A month before the McKeesport trip, Truman, accused by Republicans of coddling communists in his administration, announced a program to investigate the loyalty of government employees — long before conspiracy theories emerged of a “deep state” plotting to undermine elected leaders.

The tensions flaring around Nixon and Kennedy were symbolized by the memberships of their committees.

Sitting a few chairs away from Nixon on the Education and Labor Committee was Rep. Clare Hoffman, the seven-term Republican from Michigan who had come of age in the 19th century — and whose views reflected it. Hoffman was widely known for his attacks on Jews and was designated by radio commentator and newspaper columnist Walter Winchell as “the darling of the native fascists and Roosevelt haters.” Hoffman, now in his early 70s, endorsed the isolationist and anti-immigrant America First Party in the 1944 presidential election.

But his rabidly racist and isolationist bent didn’t affect his influence. Hoffman had recently been named chair of the Committee on Expenditures in the Executive Department, from where he would preside over a piece of legislation that proved to be one of the most significant passed that year, which both Nixon and Kennedy supported: The National Security Act of 1947, which established a separate Department of the Air Force, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the National Security Council, the Central Intelligence Agency — the permanent national security state.

On the Un-American Activities Committee to which Nixon was also assigned were the likes of Democrat John Rankin of Mississippi, who was derided the “number one race-baiter in Congress.” Black people and white people could “never live together on terms of social and political equality,” he said, declaring that America had become a dumping ground for “the maimed, the blind, the wounded … the riffraff of the world.”

Rankin once delivered a tirade against Jews on the House floor in the presence of fellow Congressman Michael Edelstein of New York, who it was widely known suffered from a serious heart condition. Rankin’s vitriol led Edelstein, despite doctor’s orders, to rise in a determined defense of his religion. When he was finished, he slowly exited the House chamber — and dropped dead.

But a new era was beckoning. Also shaping the Education and Labor Committee debates was the thunderous voice of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., of New York, who was elected two years before Kennedy and Nixon.

The tall and dapper 39-year-old preacher from Harlem was powering the nascent crusade for social and racial justice at a time when Southern congressmen like Rankin unabashedly slung racial epithets on the House floor.

Just a week before the McKeesport debate, Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in professional baseball when he played his first game for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Other tectonic shifts would soon follow, including Truman’s executive order to desegregate the armed forces.

As the train inched toward the center of McKeesport, Nixon and Kennedy saw crumbling brick row houses, many of them squalid tenements housing low-income Black people, Mexicans and the elderly.

But the town of about 50,000 nestled between the Youghiogheny and Monongahela Rivers coursed with vitality. McKeesport was a hive of furniture emporiums, movie houses, groceries, butcher shops, bakeries, bars, restaurants and 5-and-10-cent-stores — all blinking with red and green neon signs in a Babel-like hodgepodge of English, Polish, German, Russian, Swedish, Czech, Hungarian, Yiddish and Italian. Many of the storefronts advertised they were open 24 hours a day to accommodate the round-the-clock shifts at the nearby mills.

The locomotive hissed loudly as it sidled up to the Baltimore & Ohio railroad’s small, one-story red brick station. It was early evening, in a chilly drizzle, when Kennedy and Nixon stepped onto the concrete platform to see it all for themselves.

A debate and a near brawl

The Junto, the civic group that had invited Kennedy and Nixon, usually attracted middle and upper-class businessmen. But at 8 p.m. sharp, the ballroom of the Penn-McKee Hotel, McKeesport’s grandest hostelry, was filled with about 100 people — including a sizable number of union leaders and workers, some still grimy from their shifts at the nearby plants.

The recently passed House version of the labor bill had sparked an immediate outcry in the labor movement of Western Pennsylvania, where strikes were now the norm, including two recent ones at Duquesne Light that literally plunged the region into darkness. The bill prohibited some types of labor strikes and allowed states to pass right-to-work laws banning union shops. The requirement that union leaders sign a “non-communist affidavit” was viewed as an attack on personal liberties.

The moderator of the debate, a tall, crisp-mannered stockbroker with a thin mustache named William Baird, asked Nixon to speak first. The Californian launched into an impassioned defense of the labor bill.

“The public was satisfied with labor laws on V-J Day,” Nixon said of the war years. “But in the year since, we have begun to see a shift in public opinion. We have seen unprecedented labor strife — the automobile strike, the steel strike, the coal strike and even the railroad strike in which the president was forced to intervene.”

Labor leaders, he charged, opposed any changes in labor laws. “Union leaders did themselves and their unions a great disservice in their attitudes before the House committee,” Nixon told the crowd, which was growing increasingly restless as he spoke. Nixon, who had recently traveled to Scranton, Pa., to meet with union bosses and members, insisted that the bill benefited the working man and would not deprive them of any rights.

“Nixon was tense, making his points in a pile-driving way,” one of the attendees later told the McKeesport Daily News. “He had an eager willingness to get in there and fight to the last comma.”

Where Nixon was forthright, however, Kennedy was “smooth and genteel,” another attendee, a local attorney, said, as recounted by the Saturday Review. He “appeared casual, confident, more inclined to sidestep and parry than to battle.”

Kennedy countered Nixon that the bill stripped key protections from the working man. “The way some of those provisions read,” he told the audience, “the unions can’t even protect themselves from the competition of the sweatshop.”

“This bill would strike down the union shop and eliminate industry-wide bargaining and collective bargaining,” Kennedy went on. “It certainly isn’t concerned with the workers. It seeks to strangle by restraint the American labor movement.”

When Baird asked for questions, most were aimed at Nixon by angry union members. Baird had a hard time keeping control of the discussion and letting some of the more pro-business viewpoints be aired.

W.S. Thompson, the secretary of the G.C. Murphy and Co. five-and-dime chain who had greeted Kennedy and Nixon at the train station, was so upset by how Nixon was treated that he wrote him a letter of apology.

But Nixon relished the experience. “I don’t know when I have appeared on a program, which I enjoyed more than the one in McKeesport last week,” he wrote Baird a few days later. The questions from the audience, he said, “went right to the heart of the most controversial issues involved.”

“I think I had a little better of it,” Nixon recalled later.

Kennedy also told Baird he enjoyed the experience “very much.”

Afterward, Nixon and Kennedy and some of their hosts ate at the Star Restaurant, across from the train station, where one topic of discussion was sports, Clifford Flegal, another Navy veteran and local Republican leader who was there, recalled in an interview.

Then the two congressmen shared a sleeping berth on the overnight Capitol Limited back to Washington.

“We drew for who got the upper berth and who got the lower berth,” Nixon recounted, “and I won, one of the few times I did against him.”

But they slept little that night. They traded stories about their time in the South Pacific; they thought they might have been posted at the same time on Vella Lavella in the Solomon Islands, according to Nixon.

“We talked about our experiences in the past, but particularly about the world and where we were going,” Nixon said.

“Kennedy and I were too different in background, outlook and temperament to become close friends,” he wrote in his memoirs, “but we were thrown together during our early careers, and we never had less than an amicable relationship. In those early years we saw ourselves as political opponents but not rivals.”

Lasting Respect

Within less than six years they would both be senators and in little more than a decade they would square off for the presidency. But their personal bond and mutual respect lasted through it all.

When Kennedy was at death’s door after risky back surgery in 1954, a Secret Service agent riding with then-Vice President Nixon witnessed him cry and mutter that “poor brave Jack is going to die,” Chris Matthews recounted in Kennedy & Nixon","link":{"target":"NEW","attributes":[],"url":"https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Kennedy-Nixon/Chris-Matthews/9781451644289","_id":"00000180-7a3a-d0a8-aba3-ff3bf4cb0000","_type":"33ac701a-72c1-316a-a3a5-13918cf384df"},"_id":"00000180-7a3a-d0a8-aba3-ff3bf4cb0001","_type":"02ec1f82-5e56-3b8c-af6e-6fc7c8772266"}">Kennedy & Nixon. “Oh, God, don’t let him die.”

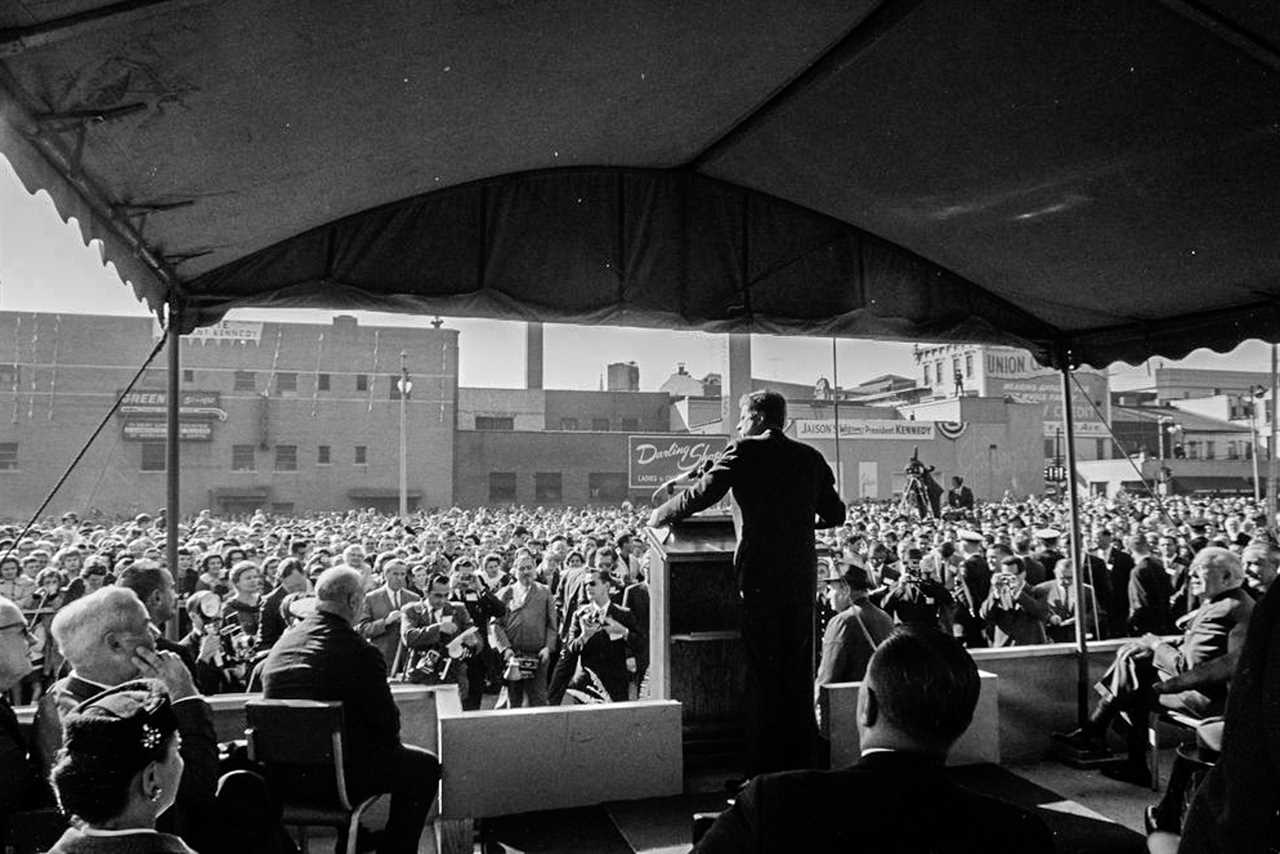

President Kennedy returned to McKeesport one more time, on Oct. 13, 1962, to stump for fellow Democrats during the midterms.

Standing in front of McKeesport City Hall in the bright sunshine, he was at the height of power. But storm clouds were also on the horizon. In just three days he would be immersed in the biggest crisis of his presidency, the 13 days of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

“The first time I came to this city was in 1947,” he began his speech to the raucous campaign crowd, “when Mr. Richard Nixon and I engaged in our first debate. He won that one. We went on to other things.”

----------------------------------------

By: Bryan Bender

Title: The Night Kennedy and Nixon Were Bunkmates

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/04/29/jfk-nixon-bunkmates-00028388

Published Date: Fri, 29 Apr 2022 03:30:00 EST