Meet Direct File, the federal government’s TurboTax alternative. It’s not perfect, but it’s a start.

It is oddly hard to file your income tax return in the US without working with a private company.

Over 90 percent of returns are filed either by a paid tax preparer or by a taxpayer using commercial software, like TurboTax, which can cost as much as $169 per cycle, plus extra if you have state taxes. To date, most of the Internal Revenue Service’s efforts to make tax filing more available to low-income people have involved throwing business to private companies through the “Free File Program,” in which those companies agree to prepare certain returns for free.

But the tax companies, preferring profit, have worked hard to make sure people don’t actually use Free File. Over its decade-plus of operation, fewer than 3 percent of eligible taxpayers used the program. The end result is these tax companies are responsible for more than 90 percent of returns filed in the US, with Americans more or less forced to give their financial information, and usually their money, to a private company.

Until this year. The 2024 filing season represents the debut of Direct File, the IRS’s new program to allow taxpayers to file their taxes directly through a government website.

But there’s a catch. Well, several catches. The program is, for now, a limited pilot, available in 12 states, representing a little under half the US population. Even in those states, the software is rolling out slowly. It only opened to general users on February 22, and then only for a small number. The IRS says it will “continue to open for new taxpayers in pilot states for short availability windows” throughout the spring.

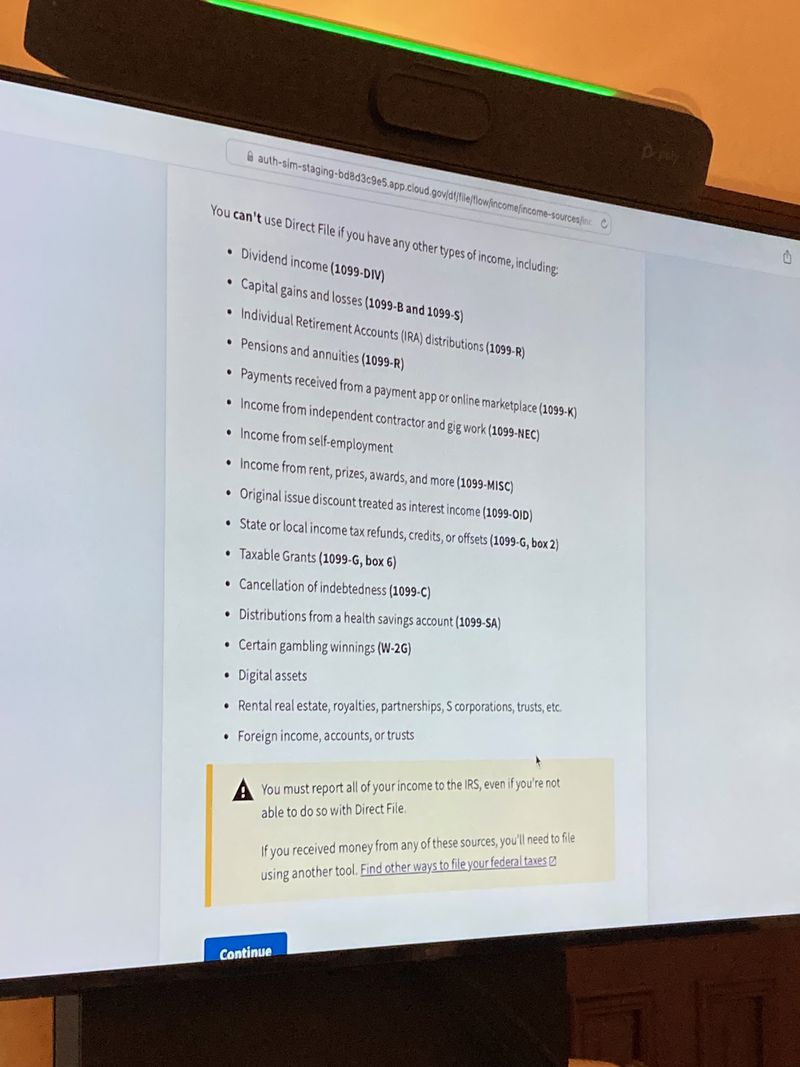

And the software is limited in what tax situations it can handle. If you have wages or salary income and/or interest income, and nothing else, you’re probably eligible. But if you have self-employment, freelance, or income from owning a business, you’re not.

Treasury spokesperson Ashley Schapitl told me the IRS estimates that about one-third of taxpayers in participating states have tax situations simple enough that they can use the Direct File software. She explained that about 19 million taxpayers, total, will be eligible this season and that the department expects “at least several hundred thousand” to participate.

This all, I have to admit, bummed me out slightly. For years now, I’ve been a booster of efforts to make tax filing easier and break the TurboTax/H&R Block duopoly on tax prep. Direct File, which is the result of a provision included in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, seemed like the first effort by the federal government to do just that, to free the tax system from these parasitic corporations.

And the first draft of Direct File didn’t feel big enough for the task. Some of the team building it showed the software off to me and a couple other journalists in January, and while the technical details were cool in a nerdy way (the program logic is written in Scala!), what I kept thinking was: This can’t compete with TurboTax. It can’t do my very simple taxes; I just have a W-2 from Vox and a couple 1099s from participating in a medical study. And if we’re not giving taxpayers something better than the private sector, what are we doing here?

The answer, essentially, is that the IRS is taking things slowly. It didn’t want to release software capable of handling all tax situations from the start because that philosophy — build it all, deploy it suddenly — is historically a recipe for disaster in projects like this. That was, for instance, what happened with HealthCare.gov in 2013. Instead of a working product, users got so many outages, delays, and crashes that a grand total of six people were able to enroll in health insurance on the website’s first day. The idea this time was to build it gradually so that each limited form of the software works before moving forward.

That might not be satisfying for impatient people like me. But it might be a wiser approach.

Limitations of the pilot

The 12 states participating in the Direct File pilot were chosen deliberately. They include eight states that don’t levy a general income tax (Florida, Nevada, New Hampshire, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming), meaning there’s no need for the IRS software to integrate with a state tax system. The other four states at least had state-level Direct File systems and opted to integrate their own state tax software with the IRS’s (Arizona, California, Massachusetts, and New York).

Alaska, the ninth state with no state income tax, was originally going to be in the pilot, but a Direct File staffer explained to me that the Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend, an annual cash payment to all residents funded out of oil revenue, is reported on a 1099-MISC. That meant basically no one in the state would be able to use the pilot software.

Early on in the software steps, users are given a couple of lists of reasons why they might not be eligible. Taxpayers who itemize their deductions won’t be able to do that in the software, for instance, and the software won’t calculate if itemizing is a better choice for you. Nor is anyone with dividend, capital gains, self-employment, or non-Social Security pension income eligible. For context, over 20 percent of taxpayers in 2022 reported dividend income.

Dylan Matthews/Vox

Users can claim the three most-used tax credits — the earned income tax credit for low-income working people, the child tax credit, and the credit for other dependents, which covers dependents other than children under 17. But other common credits, like the premium credit from the Obamacare exchanges or tax credit for child care expenses or credits covering college tuition and other higher education expenses, can’t be claimed with Direct File. Educators can deduct out-of-pocket expenses, and folks with student loans can deduct their interest, but mortgage interest, charitable, state and local tax deductions, and anything else on the “itemized” list is out. For the large majority of people, the standard deduction will still wind up being a better deal, but other tax prep software gives people tools to figure out which is better.

Add up all the left-out income types and unavailable credits and pretty soon you get to the IRS’s estimate that two-thirds of people in pilot states won’t be eligible to use the software this year.

The case for going gradually

I couldn’t use Direct File this year, both because of some 1099 income and because DC, where I live, isn’t a pilot state (or disenfranchised non-state fiefdom as the case may be). So I did my taxes in Cash App, like normal.

Cash App Taxes is a bit of a funny product; why, exactly, does an app that I otherwise only use to send my dad money for my share of the Verizon family plan offer tax prep software? Even stranger is that it’s pretty good. It’s full-featured, even handling business income and some complex expensing options, and it handles state taxes too. Plus, it’s free. The company has explained that Cash App Taxes makes no revenue and exists solely as a marketing device “aimed at attracting new customers and encouraging the usage of Cash App.” There isn’t a premium option, and as someone who’d rather do my taxes with pen and paper than give any money to TurboTax or H&R Block, I like that.

I kept wondering, as I played around with Direct File, why it couldn’t just be like Cash App Taxes. Why not just buy up existing private software? Why are we reinventing the wheel?

“A lot of states have free public tax filing systems, and the majority of the states that offer them use tax software from a private company,” Ariel Jurow Kleiman, a professor at Loyola Law School and lead author of an independent study commissioned by the IRS to investigate the idea of a Direct File system, told me. One service, GenTax by Fast Enterprises, dominates this market. So it was certainly possible for the government to contract with a company to supply software fueling a Direct File system.

But that approach comes with certain disadvantages: Enlisting private contractors raises concerns about data privacy (could this private company see my income information?) and data security (is this private company really able to secure my information against hackers?), Jurow Kleiman notes, and those are less pronounced for a government-developed product. Ayushi Roy, a veteran government technologist now at New America’s New Practice Lab, and a collaborator on the independent study with Jurow Kleiman, notes that existing private software has not been developed or optimized for the same things that we’d want to optimize Direct File for.

Cash App Taxes, say, is most optimized to get people to download Cash App, not to be maximally helpful for taxpayers currently ill-served by private options. “Even if, hypothetically, the IRS were to license” a private piece of software, Roy says, that private provider might not “be able to service customer support needs in the way that this target demographic might need, that are unique to them.”

That means the IRS probably wouldn’t be taking a product off the shelf. You’d be contracting a vendor to build a product — or modify an existing off-the-shelf similar product that vendor has built before — and then paying them to keep it updated and working well. That can be the worst of all worlds because it locks government into using one vendor going forward, even if that vendor fails catastrophically. That has happened before: Rhode Island’s United Health Infrastructure Project had a disastrous rollout, but the state still re-awarded the contract to fix the system to Deloitte, the same contractor that made it and was responsible for its failures in the first place.

Roy notes that the US has already tried heavy reliance on private developers for tax preparation. That was the basis of the Free File system, which has only served a tiny fraction of eligible taxpayers throughout its history. Relying on these companies has failed so far; building a system from scratch in-house might avoid those problems.

Of course, building the software in-house comes with its own trade-offs, not least of which is a development process where early releases have fewer features than commercial alternatives. The Direct File team is following a philosophy known in software engineering as “agile” development. Older approaches, sometimes called “plan-based” or “waterfall,” envisioned software projects as linear sequences: First you build a plan for what the software will do, then you write all the software, then you test the software.

The downside is that testing, in this approach, only comes late, after much of the software has already been written. Developers don’t get regular feedback as they’re developing that they can use to strengthen the product. Agile development, by contrast, emphasizes launching more barebones products first, enabling rapid testing and iteration, ensuring very basic features are working well before moving on to additional ones.

In government circles, agile approaches have gained popularity in part because of a case in which they were not used effectively: HealthCare.gov, which was infamously unreliable in its early months and was developed without much early testing and iteration. An Inspector General’s investigation of that debacle notes that while developers stated they were trying to use agile methods, time and resources weren’t available for the kind of rapid iteration and testing that would actually make it work. “That product, HealthCare.gov, was not allowed to have any sort of gradual rollout, not allowed to have a learning curve,” Roy notes.

The Direct File approach is sort of the inverse of the HealthCare.gov one: lots of early testing, a pilot release before a broad release, testing with a small group of government employees before pushing to the broad public, and testing a bare-bones version first before a decked-out one.

What comes next

An optimistic read of the Direct File experience is that this is just the start. The limited rollout in 2024 will lead to a more full-featured rollout in 2025, perhaps extending to more states and including more kinds of income and credits. In time, perhaps the IRS can partner with states so taxpayers can file both state and federal taxes in the same software.

Most excitingly, at least to me, a future version could feature pre-filling. The IRS already has all the information it needs: It receives W-2, 1099, and other tax documents from your employers, contractor clients, mortgage companies, and so forth. One of the strange things about filing your taxes, even with Direct File, is that you have to enter all this information. Jurow Kleiman has proposed letting future versions of Direct File, and of private software too, directly import these forms from the IRS. Recalling her work leading a team writing the independent report on Direct File, she says, “We felt there were no technological barriers to pre-filling.”

Eliminating returns or moving to a system where entire returns are pre-filled by the IRS would take a lot more work. The barriers there are at least as much about the tax code as a lack of IRS software. For instance, the ability of married taxpayers to file joint returns, an option that isn’t available in many peer countries like the UK, Canada, and Australia, makes taxes way more complicated and prevents the IRS from withholding precisely the amount people owe. Reforming that system is a good idea but a much more challenging task.

Politics, as they say, is the strong and slow boring of hard boards. And to impatient people like me, the development of Direct File can feel very slow indeed. It’s a small step toward a world where people don’t need commercial tax software. But it’s a meaningful step, and the case for taking things slow is surprisingly compelling.

----------------------------------------

By: Dylan Matthews

Title: I got to see the IRS’s free tax-filing software in action. Here’s what I learned.

Sourced From: www.vox.com/future-perfect/24071005/irs-direct-file-free-tax-software-turbotax-review

Published Date: Mon, 26 Feb 2024 11:00:00 +0000