CHICAGO — Michael Madigan battled governors, piped money into campaigns and steered the Democratic agenda in Illinois for a generation. Of all the titles he accrued over his 50-year political career — speaker of the Illinois House and “velvet hammer” among them — grand marshal at Chicago’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade was one he seemed to savor.

The parade in 2016 commemorated the 100th anniversary of the Easter Rising, when Irish nationalists, many of them laborers, rebelled against British rule and proclaimed an independent republic. And that year, Madigan and organized labor had a common enemy: Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner, who was fighting unions to create “right to work” zones. The Plumbers Local Union 130 runs the parade and saw Madigan, a pivotal figure in the state at the time who comes from a long line of Irish Catholics, as a perfect fit to lead a defiant procession.

Politicians of all stripes flocked to the event, held just days before the state’s primary election. Donning the traditional green sash and fedora, Madigan embraced his role in the celebration of the city’s bustling Irish community. He even shook hands with Rauner.

“Everyone wanted to wish him well and shake his hand and take a photo with him,” recalled Jim Coyne, business manager for the plumbers’ union and chair of the parade.

That was Madigan at his apex, practically untouchable. The Illinois power broker, in a state dominated by his party, served in the General Assembly long enough to see the minimum wage rise 13 times, and led the House when it abolished the death penalty, legalized same-sex marriage and notched other liberal victories.

But nearly six years since the parade and only nine months after he resigned from the statehouse, Madigan has left the political spotlight, and it's not clear who is running the machine in his place.

Madigan’s decline is a dramatic story in its own right, but it also represents a genuine shuffling of Illinois politics. In a state where people of Irish descent became so politically dominant that candidates were once known to change their names to gain an advantage, Madigan was one of the last leading figures of the old Irish machine to exit the arena. Now, the state’s Democratic leadership is becoming both more diverse — and more diffuse. A new generation of leaders has emerged, but they are left to figure out whether to restructure Democratic power in the state or mold themselves into the highly consolidated model established by Madigan and a political machine that dates back to the 1930s.

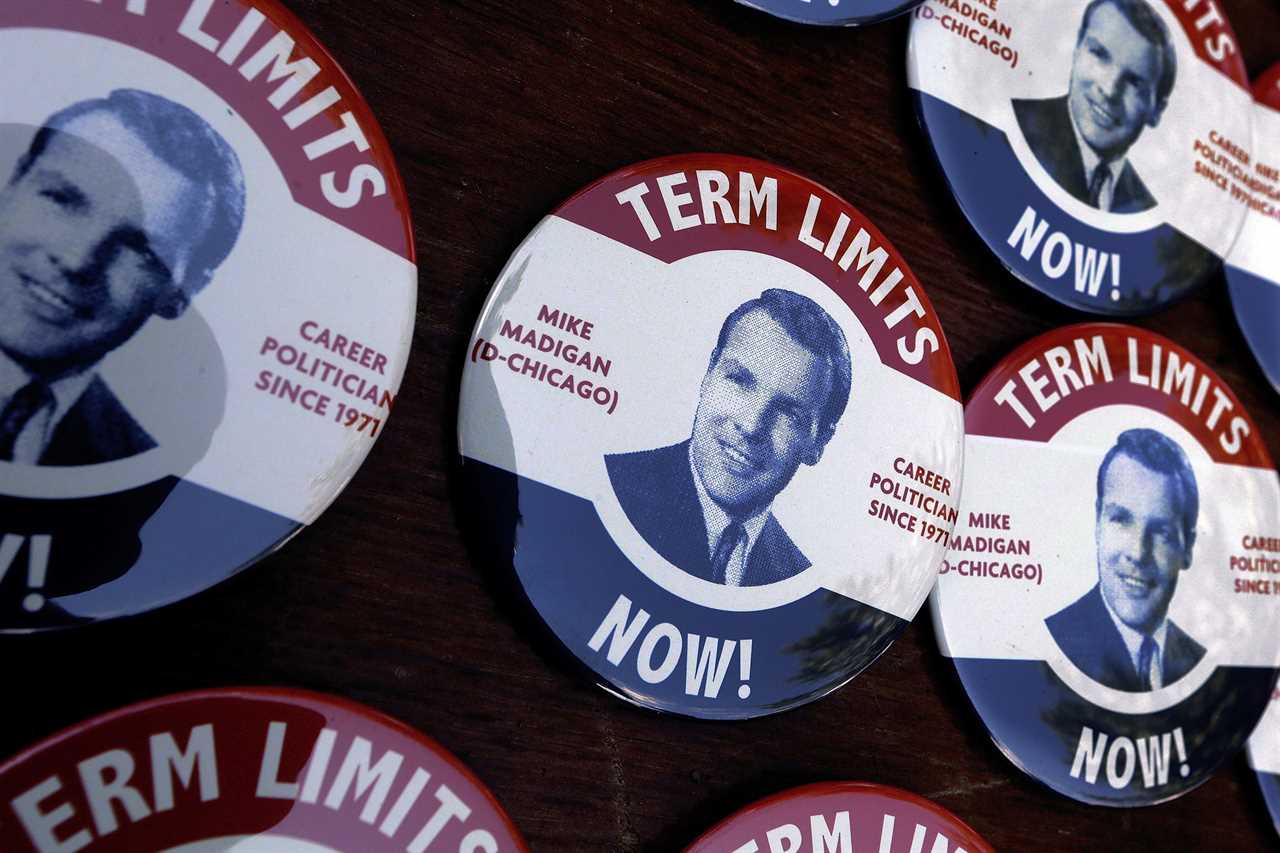

Since 2019, Madigan has been connected to, though not charged in, a federal bribery probe into the state’s largest electric utility, tainted by a top aide accused of sexual misconduct, and blamed for the Democratic Party’s lukewarm 2020 election results in Illinois. It all turned out to be enough to puncture his political armor. After decades in office, Madigan was nudged out of the speakership by his own caucus early this year at age 78, before resigning from the Legislature and his 23-year chairmanship of the Illinois Democratic Party. (Multiple requests to interview the former speaker went unanswered.)

Illinois Democrats have elected Black lawmakers to their congressional delegation for years — from former Sens. Barack Obama and Carol Moseley Braun to longtime Democratic Reps. Bobby Rush and Danny Davis. Leadership in state and local offices has evolved more slowly, but the old hierarchy is dissolving. The two positions Madigan relinquished this year — House speaker and state party chair — are now held by Black figures who came up through the ranks of the Democratic Party, and they’re working through the layers of what comes next.

“The challenge of being a Black speaker is the challenge of being a Black man in America,” Emanuel “Chris” Welch, the state’s first Black speaker and Madigan’s successor in Springfield, said in an interview. “We are under a greater microscope. It makes you want to work harder.”

Illinois is more than its largest city, Chicago, whose ever-creeping suburban sprawl accounts for greater than half the state’s population. But Democratic Mayor Lori Lightfoot, the first Black woman and first openly gay person in the job, notably campaigned as a foil to the machine-style politics the city had become known for after two generations of Richard Daleys ruled City Hall. A growing Latino community is also asserting its voice more in the Chicago City Council, Illinois General Assembly and, with newly approved congressional boundaries, the state’s delegation in Washington, D.C.

“Black politicians have taken the Irish playbook and not only are winning votes among their group or their tribe, but they’re having an ability to cross over and have a lot of appeal to people who are different from them,” said Pete Giangreco, a Chicago-based political consultant who has advised Democrats, including Obama and Amy Klobuchar, Minnesota's senior senator. “It’s not unlike what the Daleys did.”

The question is whether this new leadership wants to sever being associated with the machine.

Illinois’ increasingly diverse political leadership mirrors a similar trend across the country. Boston, for example, another longtime stronghold of Irish machine politics, recently elected its first person of color (and its first woman) as mayor — an Illinois native, no less. Some political observers here say they’ve already noticed changes in the way the new state leadership governs and campaigns, including a more deliberative legislating process in the statehouse. But love him or hate him, Democratic politicians, candidates and operatives have concerns about what it looks like when party politics no longer revolve around one man. Madigan wielded a crucial get-out-the-vote field operation, an outsized influence over lawmaking and redistricting, and could bankroll legislative races almost single-handedly.

Welch has already shown he can pick up the fundraising baton for his caucus. Now he has to prove to the party's donors — from big unions who made the backbone of Madigan’s army, to everyday contributors — that he knows how to direct the cash as well as his predecessor.

And because Madigan’s successor as state party chair, Rep. Robin Kelly, is a federal lawmaker, she can’t raise funds for local races — another disruption to the system Madigan honed for years and a political culture built over nearly a century. Both Kelly and Welch are confident about the future they’re building, even if some of their colleagues are still warming up to the idea.

“Sometimes people say they want change, and when it starts, they don’t want things changed as much as they thought,” Kelly said in an interview.

Harold Washington sparked a ‘revolution’

Chicago saw its first significant wave of Irish immigrants in the 1830s, and another in the wake of Ireland’s Great Famine. By the 1880s, they had sewn themselves into important roles in Chicago politics. Irish immigrants found opportunities by leveraging their fluency with English, while racial discrimination kept most doors closed to African Americans, said Sean Farrell, a Northern Illinois University history professor and co-author of “The Irish in Illinois.”

“English gave them a competitive advantage over Italian, Eastern European and German immigrants,” he said. “But I think we have to speak directly to the big elephant in the room, which is race. They were white. It was a dominant variable in terms of who did and did not have access to power in Chicago and Illinois.”

Another key to Irish success in government in Illinois and across the country, Farrell said, was their “ability to build coalitions” among different immigrant groups. Once in positions of authority, Irish Americans would then reward their own “disproportionately,” he said, which is why so many Irish Americans held posts in police and fire departments.

As racial minority groups grew, white leaders who had been managing relationships among European immigrant communities from Germany, Ireland, Italy and Greece began to shore up new alliances. They helped Black and brown candidates get elected and share in the success. And white leaders made sure those same groups were given jobs, propelling some of them to the middle class.

There are multiple theories about when and why this change started taking place. One school of thought points to evolving demographics. “The shift has been gradual. But you really saw it as Black and brown communities started getting more involved with each census survey and then running for office,” said Welch, the Illinois speaker.

The courts also put a damper on Irish power by ending Chicago’s political patronage system, which allowed politicians to dole out government jobs to supporters. But several of the more than two dozen sitting and retired officials, lawmakers and political consultants interviewed for this report saw a more definitive turning point: the 1983 election of Harold Washington, a Democrat, as Chicago’s first Black mayor.

“That was the beginning of a revolution,” said Rev. Jesse Jackson, the longtime social justice advocate who runs the Rainbow PUSH Coalition on Chicago’s South Side.

After Washington’s election, Jackson said, more Black candidates began to emerge from the community, instead of the Democratic organizations and committees that had ordained office-seekers for decades. A young Barack Obama was so inspired by Washington’s win that he wrote to City Hall asking about getting a job. (He didn’t get a response and instead became a community organizer.) Toni Preckwinkle, a Democrat who is now the president of the Cook County Board of Commissioners, got her start working on economic development in the Washington administration. Former Democratic state Sen. Donne Trotter, former state Rep. Monique Davis and sitting state Rep. Mary Flowers were among the people of color who volunteered for Washington’s political campaigns before going on to run for office themselves.

“Harold made people comfortable — Blacks, whites, Asians, Indians. He had worked in state government and Congress, so he was respected beyond City Hall,” Flowers said. In fact, during a meeting in his office as mayor, Washington encouraged her to run for state government. “He said I better run, and I better win,” Flowers recalled.

Washington’s short time in City Hall — he died a few months into his second term — was a “huge marker” away from Irish grip on the levers of City Hall, said Bill Singer, an attorney at Kirkland & Ellis who served as a Chicago alderman and a Democrat who ran against Richard J. Daley in 1975.

“You saw Blacks become more independent on the City Council. Blacks were no longer content to accept what the white power structure was willing to give them, the way they did in the 1950s,” said Singer, who is white. “They were no longer under the thumb of politicians who were mostly Irish.”

Democratic Rep. Bobby Rush said in an interview that Washington’s mayoralty “led to the breakup of the unholy alliance between the Irish political machine and the Black community.”

Rising Latino voices

Still, diversity in leadership moved haltingly. Roland Burris, who was Illinois attorney general for a term in the early 1990s, and Emil Jones, who served as Illinois Senate president for six years in the 2000s, were Black politicians who rose to high-level state office in the post-Washington era. Yet, as recently as 12 years ago, Chicago’s mayor, the city’s most powerful alderman, the Illinois House speaker and the state attorney general were all Irish American — as were most Cook County officials and the greater Chicago water reclamation board president.

From 1989 to 2011, Richard M. Daley — whose father, Richard J. Daley, had served as mayor from 1955 to 1976 — brought a resurgence of Irish power to City Hall. The younger Daley made a point to hire people of color and women into his administration, including Valerie Jarrett, who would go on to be a central figure in the Obama White House. Still, many Black Chicagoans saw those hires as window dressing.

“With Daley, you got some crumbs, but the community suffered,” said state Rep. La Shawn Ford, a Democrat who represents Chicago’s Austin neighborhood on the city’s West Side. “It wasn’t enough for a few people to work for the city when the whole community needed opportunities for work and to have their communities developed.”

Daley did not return requests for comment.

More recently, Chicago’s first Jewish mayor, Rahm Emanuel, a Democrat who worked for Richard M. Daley and knew how to work the political machinery built by Irish Americans, had a mixed relationship with the Black community while running the city after serving in the Obama White House. Under his watch, public school test scores went up, crime went down, the city’s finances improved and he pushed to bring fresh food and produce to the city’s food deserts. He nevertheless drew criticism for not doing enough for low-income neighborhoods on the South and West sides before his administration was eventually consumed by a policing scandal.

But now the measure of diverse political leadership in Illinois doesn’t only hinge on the rise of one non-white community. In recent decades, the rapid growth of Latinos in Chicago, its suburbs, and its exurbs, has created a new focal point in the state’s politics. About 58 percent of Illinois’ population is white, while Chicago — which defines much of the state’s politicking — is divided more evenly among white, Black and Latino residents, according to 2020 census figures. In 1983, when Madigan was first elected speaker, the African American population in the state was just shy of 1.7 million. It then peaked in the 2000 census (1.9 million), receded, and was eventually overtaken by Latinos in 2010 — a trend that continued in the most recent census.

Kent Redfield, emeritus professor of political science at the University of Illinois Springfield and an authority on Illinois politics, said the 2010 census marked another shift away from old-school Chicago. “There was a dramatic increase in minority populations. There was diversification in Chicago and Cook County but also the neighboring suburbs,” he said. “That changed the dynamic in terms of Democrats being dominated by the old Chicago politics, Irish politics.”

Madigan’s steady rise — and sudden fall

Madigan’s abrupt exit came after a storied career that started in his 20s, when he worked hauling garbage from construction sites, a job made possible by his father, who worked for Chicago’s sanitation department. Later, Madigan learned the ropes of being a boss while working in the city’s Law Department under Richard J. Daley, who would eventually give him the go-ahead to run for the state House. About 12 years later, Madigan became speaker, and his support — or disapproval — could make or break legislation and political candidates.

One of Madigan’s greatest strengths, his allies say, was his ability to thread complex issues such as abortion or the death penalty.

“If it had not been for Michael Madigan, we would not have had marriage equality in Illinois. We would not have abolished the death penalty, and we would not have been on our way to a state that is very welcoming to the ideas that people have reproductive choices,” former House Majority Leader Barbara Flynn Currie, who served with Madigan for 40 years, said in an interview. “When it came to Democratic values, there was no better leader, no better front person for those values. Without him, I think we would not be at a place where people can take off and do even more in these directions since he left.”

Currie described a fellow Democrat and a speaker who worked closely with his caucus to help them solve constituent problems and accomplish legislative goals. He listened, she said.

She sees Madigan’s departure as the result of years of vilification by Republicans — who struggle to obtain elected power in Illinois — who painted the former House speaker as corrupt. “The people who were opposed to him ultimately were able to make members of the House feel anxious about supporting him,” Currie said. “For a long time they used that tactic and for a long time there was resistance. And then finally there wasn’t.”

The public probably can’t separate myth from fact about Madigan, but most elected Democrats couldn’t really complain about his results in the General Assembly or at the ballot box. Then, after decades in power, the federal probe into Commonwealth Edison proved to be prime fodder last year for Republicans, who splashed the utility’s scandal across campaign ads — never forgetting to loosely pin the tale to Madigan.

Currie acknowledged that a federal probe into Commonwealth Edison admitting to bribery and influence peddling played a role in Madigan’s exit. He hasn’t been charged with wrongdoing but his associates have, and that hung over work in the Legislature and on the 2020 campaign trail. “There were people who stood by him who then said we can’t do that anymore,” Currie said.

After the 2020 election, where Republicans successfully beat back Betsy Dirksen Londrigan, a Madigan-supported Democratic candidate for Congress, and a progressive income tax ballot initiative that was supported by Gov. J.B. Pritzker, many Democrats sensed their moment to cut Madigan off. Pritzker, a Jewish liberal billionaire who had never held public office before and funded his own campaign, openly called on the speaker to address the “ethical cloud hanging over his head.” And Democratic Sen. Dick Durbin laid Londrigan's loss at Madigan's feet on local television. Before the end of November 2020, enough of Madigan’s caucus — the people with the power to take his gavel away — had deserted him, laying the groundwork for his departure the following February.

Stepping into the unknown

Those following in Madigan’s stead might appreciate his efficiency but want to be free of his baggage.

Welch, the new speaker, and Kelly, a freshly minted party chair, have so far promoted transparency and collaboration. They are encouraging more of their allies to be a part of decision-making and strategy, which, in government or politics, typically means more layers, more talk and more time. That has made the center of political gravity more decentralized.

State Rep. Deb Conroy, a Madigan critic who chaired the House Democratic Women’s Caucus and now is women’s caucus whip, said lawmakers are already crafting better policy in the wake of his departure.

A recent clean energy bill aimed at cutting carbon emissions passed after months of hand-wringing among environmentalists, labor unions, legislators and Commonwealth Edison, the utility whose pay-to-play scandal helped boot Madigan. Coal industry jobs were at stake, nuclear plants were threatening to close and Pritzker wanted a climate win. The process was messy — something Madigan wouldn’t have tolerated — and required lawmakers to hold a rare special session to pass it in September. Some legislators said the bill was stronger because of the more deliberative process, but some grumbled that the former speaker would have done it faster.

“That’s true,” Conroy said. “Everybody isn’t going to be happy when it’s good policy. When you strong-arm something through, there are more winners and losers, and you end up with 71 [votes] instead of the 83 who approved it with 13 Republican votes included. I don’t think that would have happened in the past.”

And when it comes to money, the Illinois Democratic Party has already been forced to diversify its political fundraising and how it supports politicians statewide — not just the state House candidates who were Madigan’s priority. It’s a change some loyal Democrats welcome: The party says it has attracted 350 new first-time contributors since Kelly became chair in September.

“As a donor, one of my fears is always that [politicians] are raising money just to raise money,” said Robert Clifford, a personal injury attorney and major donor to Illinois and national Democrats, including Obama and Hillary Clinton, who supports the new process. “It goes into a black hole versus really working for a candidate. When I’m writing a check for a candidate, I have a better chance of assessing that candidate versus donating to the bigger party.”

What happens to Madigan’s fingerprints on the Democratic get-out-the-vote operation, known as “the program,” may remain unclear until the election season is in high gear. Still, perhaps the biggest departure from Madigan’s path — in a state that has long eschewed term limits for mayors, legislators, and governors — is Welch’s interest in capping the speakership at 10 years.

But for all the change, former Democratic Gov. Pat Quinn, a proud Irishman who didn’t fall in line with Madigan or Richard M. Daley, still sees a fatal flaw: The state’s transactional politics aren’t going to change, he said — regardless of color — without new ways to hold politicians accountable. “We don’t have an initiative process where voters can put ethics measures on the ballot,” he said, pointing, as well, to a lack of conflict-of-interest laws that might prohibit lawmakers from voting on legislation they have a personal or financial interest in. “That’s the essence of machine politics.”

Illinois lawmakers recently passed a raft of ethics reforms in their 2021 session, including barring lawmakers from being employed as lobbyists in certain circumstances and requiring lawmakers to wait six months before becoming lobbyists if they leave before their term is up.

Quinn, who was governor from 2009 to 2015, summarized the law as “weak soup.”

After all, while Madigan has relinquished his most prominent posts, he still sits on the Democratic State Central Committee, the political body that provides infrastructure and helps support candidates. And he remains the boss of Chicago’s 13th Ward, with a say over local political and judicial candidates, and the power to assign jobs and prioritize some city services.

And from Illinois House Minority Leader Jim Durkin’s vantage point, nothing has changed. Just look at the recent redistricting changes by Democrats, he said, where Democrats factored in a range of political calculations.

“Virtually every Democrat in the House — including Speaker Welch — at one time or another campaigned or listed on an editorial board questionnaire that politicians should be out of the business of drawing maps," Durkin said in a phone interview. "But look at the legislative maps, Supreme Court redistricting map, and congressional map."

The redistricting panel that recently drew up new political boundaries in Illinois were also veterans of the process — and former allies, attorneys and aides to Madigan.

“The Irish are gone but the machine is in full operation, and they’re running at full speed ahead,” Durkin said.

----------------------------------------

By: Shia Kapos

Title: The Old Illinois Political Machine May Be Dying. It’s Unclear What Takes Its Place.

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/11/24/illinois-democrats-irish-political-hierarchy-521144

Published Date: Wed, 24 Nov 2021 04:30:11 EST