LINCOLNTON, N.C. — By the time Jeff Jackson got here, he already had been to 95 of the 100 counties in the state, drawing crowds in not only Democratic strongholds but reliably Republican outposts as well. Now on a steamy Saturday morning an hour northwest of Charlotte, pressing into the more rural reaches of Lincoln County where last year more than 7 in 10 voters voted for Donald Trump, this Democrat running for the United States Senate bounded across a park toward a pavilion that was packed with 130 whooping, clapping supporters. “Y’all — I can’t tell you how surprised I am by how many people are here!”

Dressed in his uniform — brown shoes, khaki pants, soft blue Oxford shirt — Jackson launched into his characteristically spirited, borderline iconoclastic spiel. He told the throng what hordes of consultants had told him about how to win — polls, focus groups, “five key phrases in five key counties!” “I said, ‘Bullshit!’” he said, leaning forward to land the punchline. “That’s how you lose!”

In almost any Democratic primary in North Carolina in almost any cycle in the past, somebody like Jackson would have been all but a lock to win. A white father to three young children, an Army veteran who spent a year in Afghanistan and a former prosecutor in a conservative county who’s now a state senator from Charlotte, he is, even his critics grant, a gifted communicator — good on the stump, good on the internet, and good face-to-face, fist-bumping his way through rope lines and meet-and-greets, making apparent inroads in places where progressive Democrats usually are persona non grata.

But this cycle is not like all those other cycles — and maybe nowhere is that more clear than in this ultra-important state in this ultra-important race. Because the candidate who’s emerging as the frontrunner is not the 39-year-old Jackson. For now, the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee is not taking sides, but by any of the most traditional metrics — polling, fundraising, endorsements — the pacesetter seems to be Cheri Beasley, who is looking more and more like a part of a wave of Black candidates who are rapidly altering the dynamics of Senate campaigns across the country, especially in the South, challenging long-held maxims about what kinds of candidates are best positioned to appeal to the mixture of voters in a region with electoral demographics that are changing just as fast and where Black candidates have historically had to run as outsiders or long shots.

Beasley, 55, is a wife, a mother to twin sons who are 20, a former public defender in Fayetteville who was elected to the state appellate court and later the state Supreme Court, a trailblazer who rose through the ranks of the state judiciary to become the Supreme Court’s chief justice — the first Black woman ever to hold that spot on the bench. In her reelection effort last year, she lost by an infinitesimal margin to the longest-serving justice on the court — even though she earned 11,000 more votes than President Joe Biden himself. Beasley would be not just the first Black woman elected to the U.S. Senate from North Carolina but the first Black person.

Jackson and Beasley are for the most part ideologically aligned, but the contrast otherwise could hardly be more stark — race, age and experience, social media reach and approach, campaign strategy and style. Jackson is bouncing-around barnstorming, while Beasley’s bid is every bit as much a reflection of her lower-key demeanor.

The outcome of this intraparty swing-state tug-of-war could determine nothing less than the balance of power in Washington, and it’s playing out, of course, in the high-stakes wake of a cycle in which Black voters — and in particular Black women in this part of the country — helped get Biden elected and helped give him even the 50-50 split in the Senate. It was a cycle, too, in which in North Carolina a white male Democrat squandered a favorable moment with a self-inflicted scandal. It’s all bringing to the fore a critical question: In the growing, shifting South, increasingly the nation’s preeminent political battleground, what kind of Democrat is the best bet to win?

While candidates like Val Demings in Florida and the incumbent Raphael Warnock in Georgia have raked in huge hauls — the sorts of numbers that scare away or simply swamp opponents — that’s not what’s happening here. This primary is still competitive. Over the last couple months, I’ve been out and about on the trail with Jackson and Beasley, three times apiece. I’ve had long conversations with more than 60 elected officials, donors, voters, insiders and operatives. These people say this North Carolina contest has gripped their attention as a matchup with electoral implications that will extend well beyond Election Day — and they are deeply anxious about making the wrong choice.

“I probably won’t know how I’m going to vote … until I walk into the voting booth,” said state Sen. Julie Mayfield.

“It’s hard when you have someone like Jeff, who is clearly smart, will work his tail off, is rock solid on the policy, and would be I think a very effective policy maker and a very effective senator,” added Mayfield, who is white. “But he is not a Black woman, and I can’t disagree with the voices that say we just need more of that perspective. And if Cheri Beasley were not qualified or competent and wouldn’t make a great senator, I wouldn’t have any problem, but she would be fantastic.”

“It’s a primary that will remain competitive until the very end,” said state Sen. Natalie Murdock, who is Black.

“Whatever happens with this race, I’m going to learn something about how the electorate thinks in North Carolina, and what kind of campaigns work,” said state Sen. Wiley Nickel, who is white, who’s running for Congress near Raleigh.

This real-time scrambling of notions and norms is riveting even to politicos on the other side of the aisle. “Is it possible we have an establishment African-American Democrat and a non-establishment white male?” Charlotte-based attorney and Republican consultant Larry Shaheen said when we talked this month. “Jeff Jackson is the anti-establishment Democrat in the race for North Carolina Senate, and Cheri Beasley has positioned herself as the establishment candidate — whether she wants to be called that or not.”

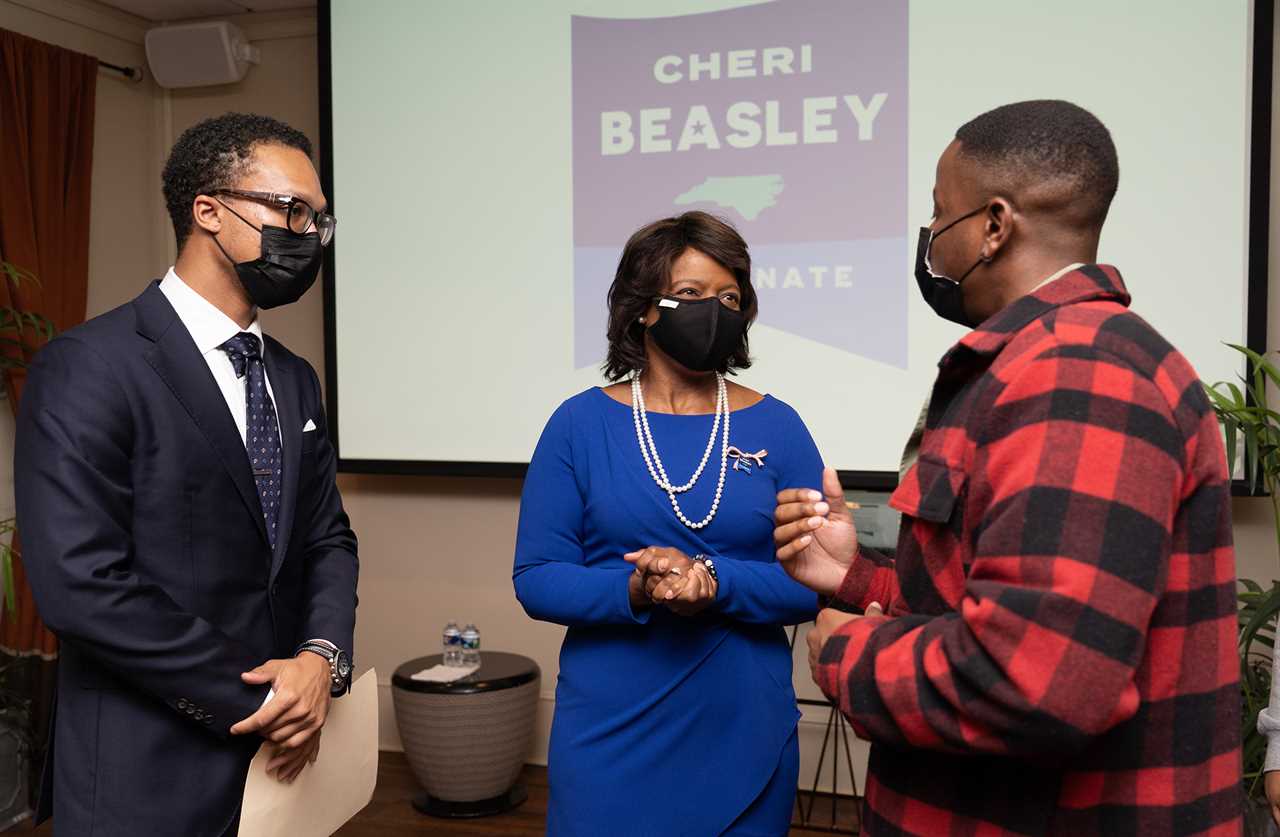

On the white walls of a quiet coworking facility a few miles north of the state capitol were signs saying WOMEN FOR BEASLEY. In a pink skirt and coat, Beasley was the last to enter the room, taking her seat at the center of one side of a conference table. “Since we’re such a small group,” she said, “let’s go around the room …”

The most immediately striking difference between the events of these two candidates’ campaigns is not just the number of people — it’s the number of Black people. With Jackson in Lincolnton and later in the day at stops in (49-percent Black) Anson and (80-plus-percent white) Union counties, I had counted a total of two (and one of them was a Jackson staffer). Now, on the other hand, here in Raleigh with Beasley were nearly 20 attendees — and the majority of them were women of color.

In a five-minute sort of miniature stump speech, Beasley led with women’s reproductive health and touched, too, on access to child and health care, infrastructure and voting rights — but what she mentioned in the middle elicited particularly noticeable nods. “I’m aware,” she said, “that there are only 24 women in the United States Senate, and there are no African-American women, and I know that it’s important that my voice is heard on the Senate floor.” She pointed to the profound importance for her of the first time she saw as an attorney a Black woman presiding in a courtroom.

North Carolina has voted before for women from both parties to be U.S. senators — Republican Elizabeth Dole, Democrat Kay Hagan — but never for a Black woman. This wouldn’t be the first time Beasley’s been a first. Her mother, a social worker with a doctorate in philosophy, was the first Black dean at Tennessee’s Austin Peay State University, and Beasley has followed suit. With degrees from Rutgers University, the University of Tennessee and Duke, she was the first Black woman to get elected statewide (without being initially appointed by a governor) when she won her seat on the appellate court in 2008. She was elected to the state Supreme Court in 2014 and became the first Black woman to be the chief justice when she was appointed by Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat, in 2019. When she was sworn in after her first election win, in the room in the capitol in which lawmakers debated the state’s secession at the start of the Civil War, Beasley wept. “We’ve got to be there for each other. We’ve got to feel that sense of commitment,” she once said in a speech honoring Dr. Martin Luther King at a Baptist church in Salisbury. “And y’all, we’ve got to vote.”

Donna Peek, a Black retired business executive across the table from Beasley in Raleigh, told me after the event she will vote for her not because she’s a Black woman but because she’s a Black woman who can win. Last year, she said, she wished she could have supported Erica Smith — a Black former state senator who is running again but has received a fraction of the final backing of her top two opponents. “The establishment was not behind her. It was behind Cal Cunningham,” Peek explained, naming the 2020 Senate candidate whose extramarital affair scuttled his shot. “And I agonized over my decision, but I was finally, like, well, if the money is going to him, and I want a Democrat in the Senate …” She even phone banked for him. “And I was particularly disappointed that I was putting my support behind a man who disappointed me. So, this time, I am going to put my heart and passion with the candidate that I feel is the best candidate, and that is Cheri Beasley,” she said. “Do we need another white man in the Senate? No, we do not.”

“Black women didn’t even abandon Cal after he probably should have been abandoned,” BlackPAC executive director Adrianne Shropshire told me. “Black women were very much, still, like, ‘We need to win this seat!’”

It’s different now. Beasley should be the pick of the voters in this primary, according to Black political strategists, activists and analysts, not because of any pent-up discontent. She should be the pick, they say, because of math. More than 60 percent of the people in North Carolina are white, but nearly 60 percent of Democrats in North Carolina are not, they note. And Beasley, they point out, although of course in very different races for very different offices, over time has racked up way more votes than Jackson has. They cite as proof of concept Georgia in 2018 — when Stacey Abrams, who is Black, faced Stacey Evans, who is white, in a hotly-watched gubernatorial primary that felt toss-up tight … until people actually voted and it wasn’t remotely close. Mobilizing a young, diverse, progressive coalition, Abrams won more than 76 percent of the count.

“The rules about electability have changed,” said Aimee Allison, the founder and president of She the People, which aims to elevate the political power of women of color. “She’s the best chance the Democrats have,” Allison said of Beasley. “When I look at North Carolina, I believe it is the Democrats’ most winnable flip — more than Ohio, more than Florida, more than Pennsylvania — and it is because of this candidate.”

“We have convinced ourselves that the only electable person is a white man,” said Ray McKinnon, a Black former Democratic National Committee member from Charlotte and a co-founder of New South Progressives. “They lose! What I’m saying is I’d like to test a new theory.”

“Black women are clinch voters and are central to the Democratic formula,” former Abrams chief of staff Jessica Byrd told me. “North Carolina’s political possibilities,” she said, “remind me of being on the ground in Georgia in 2018.”

“The Stacey Abrams playbook, to be perfectly clear, is centered around a targeted focus on people of color, particularly Black people, but definitely all people of color,” said Aimy Steele, the executive director of the New North Carolina project, this state’s answer to the Abrams-founded New Georgia Project. And the candidate matters, she said. “Is it time for us in North Carolina to have a black female senator? Yes. Period.”

Might this be a tipping point when a Black woman in the South can be considered the smart political money?

“Hell, yes!” Byrd said.

Many people in both parties look at Jackson and see more of the cookie-cutter same.

“Cal Jr.,” the National Republican Senatorial Committee has taken to calling him — a comparison GOP operatives acknowledge privately is not quite accurate or fair but also is simply too useful to pass up given the connotations it conjures for Democrats as well as the surface-level similarities between the two. Jackson, the son of a doctor and a nurse, grew up in Chapel Hill, got bachelor’s and master’s degrees in philosophy at Atlanta’s Emory University, enlisted in the Army after Sept. 11, went to Afghanistan and then UNC Law on the GI Bill and then to Gaston County to be an assistant district attorney.

Unlike Cunningham, though, Jackson is not the clear-cut establishment pick. For starters, in the fall of 2019, he rankled party bosses when he suggested to a class at UNC Charlotte — audio of which a student leaked to the National Review — that top Senate Democrat Chuck Schumer wanted candidates to vie for seats by shutting themselves “in a windowless basement raising money” to pay for negative ads. He wanted, it seemed already then, not to be defined by the party but to be seen more as an outsider or insurgent — or as much of an outsider or insurgent as a white guy in North Carolina can possibly be.

Jackson can try to run this way in large part because he has what feels like a must in the aftermath of the presidencies of Barack Obama and Donald Trump — not just a political base but something like a fanbase. Jackson’s at-the-ready online following dwarfs Beasley’s. People at his events often say they first heard of him because of viral moments he’s had — the first of which, a snow-storm tweetstorm about the laws he would pass if he could do it all on his own, got him on Rachel Maddow’s show. They say they “know him” from Facebook or Twitter or Instagram or even Reddit. “He’s actually really responsive on Reddit,” said Ashlie Jones, 32, in Anson. “I think he’s an extremely genuine person … a very transparent person … for a politician especially.”

But what strikes regulars and the rank-and-file as authentic also contributes to what rubs wrong some of the people who know him best. If he’s arm’s-length with D.C., he’s not particularly well-liked in Raleigh, either. Many (but not all) of his fellow state legislators don’t care for Jackson. “All show, no go,” as Republican Danny Britt put it when we talked. Plenty of Democrats share this view, referring to him behind his back as “Baby Jesus.” They think he’s better at generating attention for himself than he is at crafting legislation for his constituents — a show horse, to borrow terminology I heard repeatedly, more than a workhorse. They think his political persona is carefully concocted to fuel his obvious aspirations for higher office. Jackson counters that they’ve never said this to his face. Still, it’s hard not to notice that lots of his Raleigh colleagues have endorsed her, and none of them have endorsed him.

The Democrats willing to put their names to their comments about Jackson are the ones who defend him. “I’m not saying those people are wrong,” Mayfield told me. “I’m just saying my experience with Jeff has been very different.” Said Murdock: “I lean on his advice and knowledge a lot.” And Grier Martin, a member of the state House and a fellow Army veteran, challenged the criticism of his light legislative record: “I don’t think anybody in the minority in the current environment is a particularly good pusher of current law.”

Jackson has spent seven years as a state senator, but his campaign is not running through Raleigh. And some legislators say it’s not accurate to say he’s not hard-working. “He was able to pull off 100 town halls in 100 days in 100 counties,” said Nickel, the state senator who’s a former Obama White House advance staffer, “if you’re talking about a workhorse.”

Jam-packed itineraries and crowds of size and zeal matter only so much in politics — Biden, to take just the most prominent example, was not at all the hot draw in the run-up to the primaries on the 2020 presidential campaign trail — but Jackson, for what it’s worth, has pulled in crowds of 200, 300, 350 and 500 in bigger, urban Durham, Wake, Forsyth and Mecklenburg counties, respectively — and 200 in Henderson and Catawba and 130 in Carteret, all counties Trump won handily. Now, in his used Ford Fusion, riding toward a town hall at UNC Greensboro — the third leg of his current tour of college campuses — Jackson did something I hadn’t heard him do before. He outright, albeit not by name, compared his campaign to Beasley’s.

“If you have campaigns that have held 120 town halls, and you’ve got campaigns that have done virtually none, one of those is built to win a fiercely competitive general,” he said. “And the other is hoping for a blue wave that probably isn’t coming.”

“The difference,” I said, “is just … energy?”

“Energy. Yes,” he said. “I think that’s fair.”

Energy comes up a good bit in my conversations about this election — but it’s not what comes up the most. It’s hard to the point of impossible to talk for long about the differences between these two candidates without landing on race. From my spot in the backseat, I told Jackson about two of the most interesting conversations I had had during my reporting — Ray McKinnon, the former DNC member from Charlotte, and Kenneth Robinson, a Black pastor also from Charlotte.

“There are no Black women in the Senate,” McKinnon argued, “and when we’re talking about the Democratic Party, we cannot win elections without them and their voices.” He likes Jackson — considers him a friend — but he’s going with Beasley. But Robinson? He has endorsed not Beasley but Jackson. “I’m a Black man. I was raised by a Black woman, but … he’s just a better candidate,” Robinson told me. “I have a problem if we’re just picking a person because they’re a woman and because they’re Black,” he explained. “So, if we all know Jeff’s the best candidate, we’re going to do affirmative action? That’s not fair to Jeff.”

I asked Jackson what he made of such remarks.

“Dicey,” Jackson said. “Super dicey.”

He thought about what he wanted to say.

The silence in the car lasted almost 30 seconds.

“It’s not — it’s genuinely not my job to tell people what they should want out of a nominee,” he finally said, avoiding uttering a single word explicitly about race. “It is completely my job to show them a campaign that gets them excited and that compels their support.”

This to him is what that looks like: In Greensboro, in addition to answering questions for an hour in a class of international students, Jackson did his stump-plus-Q&A at an amphitheater outside a dining hall, talking as he does about health care and broadband and infrastructure and water and sewer and teacher pay and climate change and fixing gerrymandering and the decriminalization of marijuana. The person who introduced him, though, was Elijah King, a politically active sophomore from Durham who is Black.

“If you’d have asked me three or four months ago, I would’ve said, ‘He’s just another white man — we’ve got to elect Cheri Beasley.’ But guess what? Minds change. And guess what? He’s a hard worker,” King told me after the event.

“Let’s scrap the identity politics,” he said.

In Morganton, out toward the mountains, it was a gray, rainy Friday. Beasley and her campaign, though, were feeling buoyant.

They had announced the day before that she had raised in the third quarter $1.5 million — far less than Warnock’s $9.5 million and Demings’ $8.5 million but measurably more than Jackson’s just over $900,000. Beasley had added, too, the endorsement of End Citizens United to a spate of important others: EMILY’s List, the Collective PAC, the Higher Heights for America PAC, the Congressional Black Caucus PAC, more than two dozen current and former state lawmakers, Charlotte civil rights icon Harvey Gantt and Rep. Alma Adams — Jackson’s member of Congress. In the Charlotte Observer, Michael Bitzer, one of the top political scientists in the state, said Beasley “can claim frontrunner status.” I texted Raleigh-based Democratic strategist Morgan Jackson (no relation to Jeff) to ask if he agreed. He did. “Bad cycle” for Jackson, he said. “Timing is everything in politics.”

Late morning, in a room in a rec center, the white mayor of Morganton introduced Beasley — as a judge, as a mother and as a “a good friend,” but also as a winner. “She was elected in 2008 to the North Carolina Court of Appeals by 15 points,” Ronnie Thompson said to the 20 people on hand, again more women than men, again more Black and brown than white.

“That was her first statewide election — the second one was in 2014 — elected as an associate justice to the North Carolina Supreme Court. If you remember 2014, that was a real strong Republican wave, and yet she still was able to pull it off,” Thompson continued. “This Senate seat next year needs to be flipped. And this is a woman who can do that flippin’.”

In her 13-minute speech, Beasley put into the context of “justice” just about everything she mentioned — education, infrastructure and broadband, voting rights, climate change and paid family leave, child care and health care and mental health care and rural health care. “It was the pursuit of justice that led me to law school to be a judge and to be a chief justice. And it’s still the pursuit of justice that leads me to run for the United States Senate,” she told them.

But she also got to the issue that in the end of course is what matters the most. “North Carolina is the best opportunity to flip a seat in the nation,” she said.

“How do we win? We win the way we’ve been winning. The mayor told you that I, in this last race with 5.5 million votes cast, fell short by 401 votes. In that election, I received 125,000 more votes than Cal Cunningham, 30,000 more votes than Thom Tillis, 11,000 more votes than Joe Biden. And if you look at the comparative map, you will see that President Biden performed very well in urban communities, and I performed well across the state, in urban and rural communities,” Beasley added.

“We can do this,” she said.

Throughout her speech, though, I couldn’t help but notice an odd game of cat-and-mouse unfolding across the room. A stout Beasley aide kept trying to block the view of a man who was recording her — the so-called “tracker.” He works for America Rising, the GOP-affiliated opposition research firm that follows Democratic candidates to compile tape for ads and such. These days for both parties, it’s standard practice. And practically everybody who’s been to a Jeff Jackson event this year knows this tracker because Jackson has co-opted him as a prop — literally introducing him to his crowds as “a nice young man from the Republican Party” who records everything he says or does, and that’s “fine,” he always emphasizes, because “you should have a candidate who’s confident enough in himself to be caught on camera answering your questions.”

Beasley’s aide was still trying to intermittently block the tracker’s view when she opened it up for questions. After four questions in seven minutes, the mayor stood up. “One more question,” he said. Already? A radio reporter from Charlotte had arrived around 20 minutes late — and he missed almost the entire event.

As Beasley took some pictures with people who had come to see her, I talked about her fundraising and her endorsements with her communications director, who resisted any talk of Beasley being the “establishment” option.

“Establishment-supported candidate?” Beasley said when she joined us. She eyed me over her black mask. “I’ve been in service a long time, over a decade in statewide elected service. I’m really excited about where we are in this campaign. Even before I entered this election, I was polling ahead of the other Democrats in this race, and we’ve been consistent in that. And our whole point really has been to travel across the state and have constructive conversations.”

In spite of launching three months later than Jackson did, Beasley has held more than 90 events, according to her campaign, stretching from Asheville to Elizabeth City. Relative, though, to Jackson’s tour across the state, Beasley’s events often can feel staid, and more like a frontrunner’s play-it-safe pit stops.

“Why aren’t your events longer?” I asked.

“It was an hour, wasn’t it?” she said.

Technically, including the one-on-one get-togethers, but my recording of the mayor’s introduction, her speech and the question-and-answer session ran 26 minutes. And the shenanigans with the tracker made me curious. America Rising doesn’t have to sort out the Democrats’ knotty internecine wrangling. Their only goal is to have as much useable material ready to take aim at whichever candidate ultimately is on the other side in next year’s general. “We try to go every single event,” America Rising’s Joe Gierut told me. And after Morganton, the organization had a total of just shy of seven hours of footage of Beasley.

And of Jackson?

Some 83 hours. Almost three and a half days of Jackson talking in public.

So who is the best bet for Democrats here?

On my drive down from Morganton toward Davidson College, where Jackson was scheduled to have in the afternoon another town hall on his ongoing campus tour, I called a Republican consultant based in the state whose opinion I respect.

“She’s a better bet in the general, and she’s a better bet in a Democratic primary,” this person said. “If you look at the shifting demographics of North Carolina, if Democrats are going to look to maximize their turnout in midterm election cycles, they need candidates at the top of their ticket who are reflective of their party. Beasley’s more reflective of the Democratic Party than Jeff Jackson is.”

It made me think of what else I’d heard from a wide variety of others who have been watching this race and are invested in its outcome. The out-loud agonizing is remarkable; tired and bruised, ranging from cynical to sympathetic, the people I spoke to are torn by where their party is and where it should be, between wanting to be part of a transformational moment and the fear that elevating a trailblazing candidate might still fail to capture the ultimate prize.

“Let me say this clearly,” said Robinson, the Black pastor who’s supporting Jackson. “We need more diversity in the Senate — yes, we do — but we need a candidate that can win. And Jeff can win the general election. I’m not sure she can.”

“This is such a delicate topic,” a white male Jackson donor who calls himself “a pragmatic progressive” told me. “Number one, we are making progress in this state about race; number two, it is a state of the old Confederacy; and number three, we have a population of people … who remain prejudiced, OK? Let’s just say it. It’s just true. And so, I think, as unfair and as unjust as that is, probably when you are going to have a very close race — like, Cheri as chief justice, she was doing a great job, and she lost. Why did she lose? I just think race is a factor,” he said. “The best chance to win is a white guy.”

Others have no interest in such deference to a racist past.

“It makes no sense in North Carolina,” McKinnon argued, “especially in a Democratic primary, where we cannot win dog catcher without Black women, to not elevate just an incredible Black woman.”

“If you look around and you’ve got to figure out who to trust, default to a Black woman,” said Lori Gilcrist, a white woman and registered independent who is the director of a rural nonprofit that works with children and families in the western part of the state. “I have seen, especially here in the state of North Carolina, so many white men, usually veterans, who are what passes for a liberal Democrat in the state of North Carolina who have some October surprise that comes dancing out of their closet and they get clobbered. I don’t need to go there again.”

What works in the primary might not work in the general. To go back to the example of Georgia in 2018, for instance, Abrams trounced Evans — then lost to Brian Kemp that November. It was tantalizingly close. It was still a loss. So Democrats here mull and fret.

“It is about as fascinating a question as we’ve had in North Carolina primary politics as I can recall because of the contrast,” said one. “It’s kind of like Beasley and Jeff are the polar opposites. It’s like he’s a great communicator with no gravitas, and she has all the gravitas and is doing an atrocious job of communicating,” said another. “Cheri Beasley is almost the opposite of him in that the political world wanted her to run,” said a third. “But she’s not working like he’s working.”

“Jeff is incredibly charismatic, and there’s a lot of energy around him, and he projects a lot of energy, the vast majority of it positive, and I think a lot of people respond to that,” said state Rep. Brian Turner, who’s endorsed Beasley because she’s run successfully statewide and on account of her administrative experience in her Supreme Court role. But there’s a factor that’s also important to Turner, who is white. “It’s time for something a little different,” he said. “I would like to see Democrats nominate a person of color.”

Doug Wilson is a Black Democratic consultant based in Charlotte. He was an aide and adviser in North Carolina to the Obama and Biden campaigns. He’s now a senior adviser to Jackson’s campaign. “Regardless of your race, you have to earn our vote, and one thing that Senator Jackson has been doing is working hard,” Wilson told me. “He can’t change that he is a white man, but I don’t think that it should be something that will discredit him for at least making the case about why the way that he is running his campaign — the way that he’s speaking to voters, the strategy he’s putting out there — is a strategy that could be different in the general election and help us win a U.S. Senate seat for the first time since 2008.”

In Davidson, at the student union, the room was close to full. People stood in the back. Jackson went through his routine — “I said, ‘Bullshit! That’s how you lose!’” — before opening it up as always to questions. “A dangerous thing for a campaign to do at any level,” Natasha Marcus, the local state senator, said when we talked at the event. “To take any question? With cameras rolling?”

After the hour was up, post-fist bumps, I caught up with Jackson. The Senate Democrats’ campaign arm is not tapping one or the other — “still in an assessing phase,” say staffers there — but Jackson had told me on the drive back from Jackson that he didn’t want the endorsement of the DSCC. “I would say please don’t,” he said. “Which is what I’ve already told them.” Now I asked if Beasley was the de facto establishment pick at this point in this race. He said no, but he added: “She is more than I am, I think, based on endorsements.”

And I brought up Stacey-versus-Stacey, Georgia, 2018, telling him it had come up again and again in my reporting.

He nodded. “Oh, right,” he said.

“Which Stacey are you?” I said.

Jackson started to answer: “I cannot possibly invoke, I cannot possibly appropriate …”

“What a Kobayashi Maru that is,” Jackson’s press secretary warned, cutting in with a Star Trek reference meaning a no-win scenario.

Jackson continued with an answer anyway, and in a way that was surprising if fitting for a candidate who says for now he doesn’t want the support of the national party.

“We are following the Stacey Abrams playbook,” he told me matter-of-factly. “The Stacey Abrams playbook is organizing not just to get out the vote but to expand the electorate,” he said. “It’s there,” he added, “for anybody who wants to do it.”

A week and a half later, after an evening event in Durham at Duke University at the Mary Lou Williams Center for Black Culture, I told Beasley about what I had asked Jackson and how he had answered.

“I won’t go there,” she told me.

“I’m Cheri Beasley,” she said.

“I’m always Cheri Beasley.”

----------------------------------------

By: Michael Kruse

Title: The Future Face of the Democratic South

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/10/29/cheri-beasley-jeff-jackson-north-carolina-senate-race-517215

Published Date: Fri, 29 Oct 2021 03:30:00 EST

Did you miss our previous article...

https://consumernewsnetwork.com/politics-us/weary-dems-continue-to-live-through-infrastructure-week