On May 4, less than 48 hours after a draft opinion was published showing the Supreme Court was poised to end the federal right to abortion, a group of eight strangers gathered around a conference table in the Detroit suburbs to talk about the news.

They were all white women, mostly in their 30s to 50s and without college degrees. Their home county, Macomb, had voted for President Barack Obama twice and President Donald Trump twice. In the upcoming gubernatorial race, they were undecided, frustrated by how Democratic incumbent Gretchen Whitmer had handled the pandemic.

But when it came to the possibility of abortion being illegal, there was no equivocation: The women were stunned — and enraged.

It was the kind of conversation women everywhere were having with their mothers, sisters, daughters and friends. But behind a glass window in that conference room and tuning in over Zoom, a half-dozen consultants and staffers from Whitmer’s reelection campaign and the pro-abortion rights group EMILY’s List listened to likely the first Democratic focus group conducted in the wake of the report.

The moderator peppered the women with questions about the draft opinion and the possibility it would trigger a 1931 law outlawing nearly all abortions in Michigan. Then she turned to a recent comment from a Republican candidate that the Whitmer team had considered relatively tame, compared to other GOP reactions. Businessman Kevin Rinke had said that when it came to pregnancy, “There are choices that go into our lives, and there’s cause and effect, so people maybe need to consider their choices.”

The remark “elicited a lot of, ‘Fuck this guy and fuck all the guys out there who think they know better than women,’” said Molly Murphy, the Democratic pollster who moderated the discussion in early May. “This was not just about rape and incest and ‘no exceptions,’ which is obviously all very important, but it said so much more about control, about politicians who think they know better than these women — it added a layer to this that none of us were expecting.”

After the nearly two-hour session, Whitmer’s pollster Brian Stryker turned to campaign manager Preston Elliott and said: “That’s the best I’ve felt about this campaign’s position in a year.”

Days earlier, the 2022 election looked bleak, if not disastrous, for Democrats. President Joe Biden’s approval ratings hovered in the low 40s, gas prices were ticking up, and crime in big cities was high. And then there was the hard historical truth: Since World War II, presidents had lost an average of more than two dozen House seats and four Senate seats in midterm elections.

But in that focus group in Michigan — and, in the months ahead, dozens of others held by Democrats and Republicans across the country — campaign strategists kept making the same startling finding: Abortion hadn’t simply awakened Democratic voters. It was actually persuading swing voters. The memo, obtained by POLITICO, called it a “massive vulnerability for Republicans” — a conclusion bolded and underlined.

On Election Day, voters in critical states like Michigan and Pennsylvania ranked abortion — not inflation or crime — as the most important issue in the midterms, according to exit polls. The red wave never arrived. Instead, Democrats gained a seat in the Senate and Republicans, badly underperforming expectations, barely took back the House. Democrats also held onto a slew of governor’s mansions, from Wisconsin to Oregon, that otherwise may have slipped out of reach, and won control of four legislative chambers. Republicans failed to flip a single one.

How abortion shaped the 2022 midterms is, nevertheless, a mixed portrait of state-by-state results, where some Republican candidates prevailed even with staunch anti-abortion positions, such as in the governor’s races in Georgia and Florida, while Democrats in deep-blue New York suffered heavy losses. Yet, in many battleground and red-leaning states and districts, especially where Democrats spent millions to keep it at the forefront for voters, abortion access played an outsized role, reversing the party’s once abysmal outlook.

This account of how abortion affected the first election after the fall of Roe v. Wade is based on interviews with more than 50 elected officials, campaign aides and consultants from both parties.

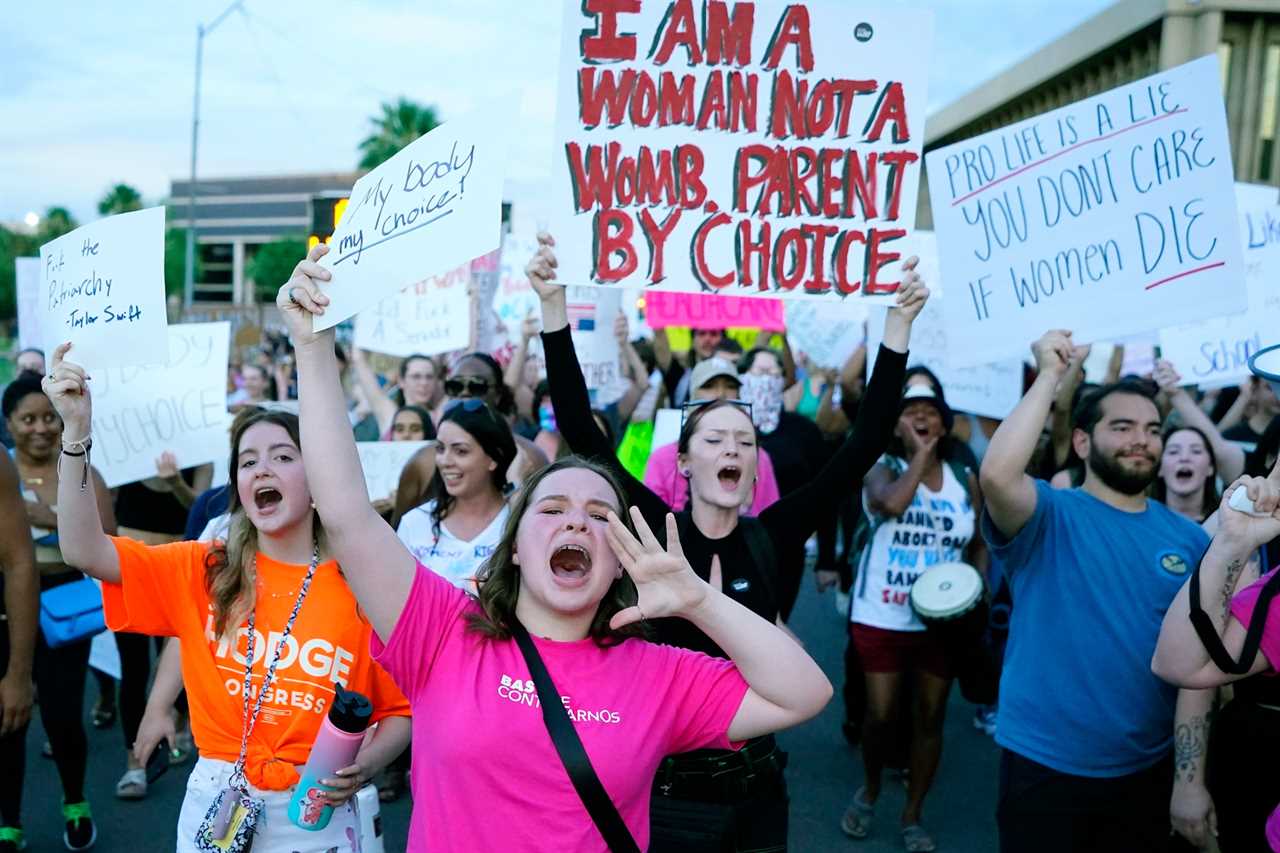

The Supreme Court decision that ended a nearly half-century of federal abortion rights triggered a fierce backlash against the Republican Party from the suburbs of Philadelphia to the plains of Kansas. It mobilized the liberal base, enabled Democrats to effectively paint GOP candidates as too extreme among independents, and even turned off some Republican women — something that some party officials even saw happen within their own families.

And unlike the Republican Party’s other headaches this cycle — money woes, flawed candidates, and even Trump — Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization cannot be undone anytime soon. Democratic and Republican operatives said that means abortion is poised to play as big a role, if not bigger, in upcoming elections, triggering a dramatic shift in political strategy as liberal groups target more states for abortion-related ballot initiatives.

“Abortion access is a core value that hits you in your gut,” said Stephanie Schriock, the former president of EMILY’s List. “It is going to be a huge part of every election going forward until we get this right back.”

When abortion was an afterthought

At the start of the midterm election cycle, many Democrats feared abortion would be a dud — even those who believed Roe would likely be overturned.

When one top Democratic super PAC interviewed voters in battleground states in the winter of 2021, they were adamant that abortion rights were safe even after the Supreme Court declined to block a Texas law that would ban abortions after about six weeks.

“They didn't really believe that Roe v. Wade was going anywhere,” said JB Poersch, president of Senate Majority PAC, the leading outside group for Senate Democrats.

Abortion rights had long been treated as an afterthought in Democratic campaigns. In House, Senate and governor’s races in 2018 and 2020, they mentioned the issue in only 2 percent of their campaign ads, according to the ad-tracking firm AdImpact.

“People were uncomfortable making ads about it,” said Martha McKenna, a strategist who held top positions at the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee and EMILY’s List. The abortion-related ads that did air were mostly produced by men, she said, and typically featured a middle-class white woman holding “a cup of tea, staring out her window at the rain, pondering her abortion,” which “could not be further from reality.”

The Virginia governor’s race in 2021 had also set off alarm bells in Democratic circles that even the looming end of abortion rights might not motivate their voters. Republican Glenn Youngkin, who identifies as “pro-life,” sustained millions of dollars in abortion-related attack ads from Democrat Terry McAuliffe and still won the race by 2 percentage points.

The reluctance to forcefully seize on abortion as an issue seeped into the early advice Democratic officials gave to candidates this election cycle. After the reversal of Roe, though, some Democrats made a big bet on abortion, anyway.

Overnight, a potent weapon

Michigan Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer knew abortion rights were in jeopardy, but the reality truly sunk in on a Friday night in September 2020 when news broke of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death. Her phone lit up with messages from friends and colleagues “just stunned about what we were on the precipice of.”

To her daughters that night, Whitmer “walked [them] through what I thought could possibly happen with a Trump [Supreme Court] appointee,” she said in an interview, “and here we are.”

But preparations for how she might respond to a post-Roe world didn’t kick into high gear until a year later, after the Supreme Court declined to intervene in the Texas case. Whitmer’s campaign jumped on comments from their likely GOP opponents about the 1931 Michigan law that would be triggered if the high court struck down Roe.

Plans were already underway to take the issue to the November ballot by enshrining it in the state’s constitution. By April 2022, Whitmer filed a lawsuit challenging the nearly century-old law, asking her state’s Supreme Court to take up the case immediately.

About 600 miles east in Pennsylvania, Democratic gubernatorial candidate Josh Shapiro was adopting a similar posture.

Then the attorney general, Shapiro had challenged anti-abortion laws in Texas, Mississippi and South Carolina. His first negative ad slammed Doug Mastriano, his Republican opponent, over his support for a no-exceptions abortion ban. And abortion was already a key part of Shapiro’s stump speech.

Despite all their preparations for the Dobbs ruling, they were still shocked when it dropped on June 24. Campaign offices, populated by young staffers, are often hives of chatter. But that morning it was eerily quiet at Whitmer headquarters. The only sound came from TV monitors showing women screaming or cheering outside the Supreme Court.

One Whitmer staffer confided that her mother had gone to the pharmacy to load up on Plan B, the morning-after contraceptive pill, for her and her sisters.

In Philadelphia, before leaving the office that evening, Shapiro’s campaign manager Dana Fritz penned a Slack message to the other women on staff: “It's been a shitty day,” she wrote, but “just wanted to send y’all a note that we should go to bed tonight knowing we've got a real role to play in protecting so many other women.”

The campaign machinery of both parties kicked into gear. Tudor Dixon, the future Republican gubernatorial nominee in Michigan, called it a “day of celebration.” Mastriano cast it as a “triumph,” while trying to shift the focus to inflation and crime.

Meanwhile, a constellation of Democratic outside groups, from the Democratic Governors Association to labor unions, jumped in. They decided in a series of conference calls that they’d go after Mastriano over abortion, not his attendance at the Capitol riot on Jan. 6, as their first line of attack. Schriock said it “took some work” to get “everybody on board” with the strategy.

But it quickly became clear how potent a campaign issue abortion had become. Shapiro’s campaign launched a texting program to win over swing voters through abortion messaging, and it proved so successful that his campaign began aiming it toward voters less and less likely to back the Democrat. And it kept working.

“I heard about [abortion rights] everywhere I went,” Shapiro said in an interview, “including from people who are lifelong Republicans who would say to me, ‘I've never voted for a Democrat, but I'll be damned if I'm gonna let that guy take away my right to make decisions over my own body, or my daughter’s right.’”

Attacks, counterattacks

Across the country, Democratic candidates and allies up and down the ticket were making the same calculation. In 2022, 27 percent of Democratic ads for the House, Senate and governorships talked about abortion, 13 times higher than the share of Democratic ads that mentioned it two years earlier. Republicans, on the other hand, largely avoided the topic: Only 5 percent of GOP ads mentioned abortion.

“If you would ask me a cycle ago, I'd probably say, ‘You talk about abortion in Philly. You probably don't talk about it anywhere else,’” said Devan Barber, the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee’s senior political adviser. “This past cycle we saw it resonate in broader parts of the state, in media markets where you may not expect.”

In total, Democrats sunk nearly $358 million into abortion-related ads in House, Senate and gubernatorial races, according to AdImpact. The spending ensured that abortion was front and center for voters in battleground states, even when the topic fell out of the news cycle, several Democratic operatives said. Republicans, in contrast, spent about $37 million on abortion-related ads.

“It used to be the stereotypical Western Pennsylvania [Democrat] was pro-life or tiptoed around being pro-choice,” said Rep.-elect Chris Deluzio, who won a Pittsburgh-based seat. “But as you saw with me, with [Sen.-elect John] Fetterman, with Shapiro, we were all strong on it and we all did well.”

He added, “You’re seeing Democrats around here be able to talk about it differently, and I think voters, whatever their political affiliation, [are] rejecting the extremism of Republicans on it.”

The disparity in spending on abortion-related ads meant that many Republican candidates didn’t offer counter-messaging to the attacks labeling them as outside the mainstream. In Pennsylvania’s Senate race, super PACs supporting Fetterman hammered Republican Mehmet Oz over abortion on TV. Oz’s campaign considered fighting back in an ad of their own, according to multiple people familiar with the talks.

But Oz’s team made the calculation that it was best not to give them oxygen.

The National Republican Congressional Campaign also advised candidates and campaign operatives “to ignore it,” said one consultant who works on House races. “That was their mantra.”

Instead, they urged members and candidates to pivot to the economy and crime. Many candidates followed the advice because “every time we’re talking about [abortion], we’re taking away our ability to talk about something else that’s advantageous,” said Jason Cabel Roe, a Michigan-based Republican consultant who worked on Tom Barrett’s unsuccessful bid to unseat Rep. Elissa Slotkin (D-Mich.).

Some Republicans who did address abortion head-on still had trouble persuading voters. Colorado’s Joe O’Dea, who challenged Democratic Sen. Michael Bennet, put his daughter on camera to explain to voters that her dad is “a different kind of Republican” who “supports a woman’s right to choose.” But his message was drowned out, Republican operatives said, by the lopsided spending advantage for Bennet. Ultimately, it wasn’t enough to pull O’Dea even within striking distance to Bennet, despite strong Republican turnout in the state.

“In these true swing states, if abortion rights are dramatically threatened, it’s going to be really hard to win as a Republican in this new normal,” said Zack Roday, a Republican consultant who advised O’Dea.

‘When you run away, you lose’

Even in late October, Democrats were divided over whether abortion would make a significant difference for them. Polls showed statewide races shifting toward Republicans. Some Democratic operatives said abortion and democracy weren’t moving many independent voters. Other party insiders fretted that the candidates they nominated in key races were coming up short.

No Senate race loomed larger than Pennsylvania’s. Fetterman had led Oz by a wide margin for much of the campaign. But by the time they met for their first and only debate on Oct. 25, the race had narrowed to a statistical tie.

Fetterman, who had suffered a stroke months earlier, was difficult to watch. He struggled to complete sentences and paused awkwardly — setting off panic in real time among Democrats.

But a response by Oz to a question about abortion gave Democrats the opening they needed to change the subject.

Some on Fetterman’s team went into the night thinking Oz would announce that he opposed Sen. Lindsey Graham’s proposed 15-week abortion ban in an effort to appeal to moderate voters. Instead, Oz said that “women, doctors, local political leaders” should have a say in abortion policy.

Barber, the DSCC’s senior political adviser, couldn’t believe it: “It's like we scripted it for him. You could just feel we struck gold.” She jumped on a group chat with the Fetterman campaign. “I was like, ‘I know everyone's really busy, and we're all doing a lot of things, but I think we need to make an ad on this — literally right now,” she said.

The digital spot, which tied Oz to Mastriano, was out by the next morning. “And it honestly framed a lot of the post-debate coverage,” said Barber.

Oz’s campaign was pleased with how the debate went. But on the broader question of how abortion affected the race, people in Oz’s orbit think it played a role in his loss.

John Fredericks, a conservative radio host who campaigned for Oz, said the celebrity doctor was a “great, disciplined candidate.” But he said it was a mistake for Republicans to not fight back against Democrats’ abortion attacks on the airwaves.

In what was projected to be one of the closest Senate elections in the country, Fetterman defeated Oz by 5 percentage points, 51 to 46.

“When you run away, you lose every single time,” Fredericks said. “And that’s what the Republicans did.”

Democrats, however, came away from 2022 confident that Republicans will be on the defensive over abortion for many election cycles to come. After succeeding in all six of their state ballot referendum fights this year, progressive groups have sprouted in Ohio and South Dakota and are working to put ballot measures before voters. More are expected in Missouri, Oklahoma and Arizona.

“When we take this out of the hands of politicians we can get some exciting results,” said Rachel Sweet, who led the successful campaigns to defeat anti-abortion constitutional amendments in Kansas and Kentucky.

Not every state, however, allows for voters to change their state constitution via referendum. So state elections will play a key role in Democratic efforts. After their success this year, Democrats are already eyeing legislative races in Virginia and special elections in New Hampshire are coming in 2023.

In Michigan, Democratic state Sen. Mallory McMorrow said that statehouse candidates who ran on protecting abortion rights saw a surge in fundraising, allowing them to hit the TV airwaves first. In addition to Whitmer’s win this fall, Democrats flipped both chambers there, and McMorrow is already talking to other state legislators about how “Michigan can be a playbook” for them.

In Pennsylvania, Shapiro’s commanding 15-point victory over Mastriano helped Democrats there win the majority of statehouse seats for the first time in years.

Sheryl Bartos, the wife of Oz campaign co-chair Jeff Bartos, was one of the Republican women who crossed party lines to back Shapiro. Her decision was motivated, in part, by Mastriano’s position on abortion.

“Moderates and independents in [Pennsylvania] are not going to support candidates who are pro-life with no exceptions,” she said.

Going forward, hard decisions for the GOP

Five weeks after Election Day, on Dec. 12, two more groups of women convened in Phoenix to talk about how they voted.

They were a mix of unaffiliated, independent and Republican voters, all of whom either split their ticket between Democrats and Republicans, voted for a Libertarian candidate, or left at least one race blank on their ballot. Their home county, Maricopa, one of the fastest-growing in the country, voted Democratic in a presidential race in 2020 for the first time in decades.

The women were frustrated and embarrassed by the election. They described Trump as a “central and unwelcome figure,” while others largely viewed Biden as a non-factor who they didn’t blame for inflation or problems at the Southern border.

But when it came to abortion, it was personal: When the moderator asked if the women themselves or someone they knew had an unplanned pregnancy or abortion story, every single hand in the room shot up.

For them, it wasn’t just about a medical procedure. “It’s about control, controlling women and suppression of women,” said one independent voter.

“It’s a slippery slope,” said another, a Republican. “If they are demanding control here, where does it end?”

“Every single woman [who] has been in a relationship has experienced the ‘being late’ moment,” said Jessica Pacheco, an Arizona-based Republican strategist. “Every woman can relate to that, but it’s an intangible that’s hard to explain to men.”

The women were gathered by GOP strategists trying to sort through what happened in 2022. The focus groups, described in a memo obtained by POLITICO, were conducted by Republican pollster Nicole McCleskey — and they represent likely the first post-election data on how abortion shaped swing women voters' decisions in a suburban county in a battleground state.

“Aside from Trump,” the memo stated, “abortion was THE central issue of the campaign.” What the women “considered extreme abortion positions,” plus Trump’s “influence,” it said, “took Republican candidates out of consideration for many of these women, including women who consider themselves pro-life.”

The document pointed to some success stories, like Republican Arizona state treasurer Kimberly Yee and Maricopa County Attorney Rachel Mitchell. But it was blunt in its assessment that GOP nominees Blake Masters for Senate and Kari Lake for governor were “the caricatures of extreme Republicans this election according to these women.”

Masters, who challenged Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.), backtracked on his abortion position during the general election, scrubbing “I am 100% pro-life” from his campaign website. Lake, who lost to Gov.-elect Katie Hobbs, struggled to precisely define her position.

“Gone are the days where you can say, ‘I’m pro-life,’ ‘I’m pro-choice,’ and leave it at that. Because those labels are confusing, they mean different things to different people,” Pacheco said. “To win, you need to walk through your values and what the issue means to you.”

Without Roe, Republicans now face an array of existential questions heading into 2024: Do they unify around a national abortion ban, like Graham’s bill? Do anti-abortion activists push for even stricter restrictions federally? Or do they let candidates decide their own positions?

An open presidential primary could help define the contours of the party’s position. But some GOP operatives argue that it might be best to let this play out race-by-race, so candidates can adapt based on their personal beliefs and the values of their particular state or district.

Still others say Republicans need to turn the issue around on Democrats by arguing that abortion with few or no limits is the extreme position.

At the same time, Republicans acknowledge privately that there’s broad discomfort in taking on this issue, in part because it tackles deeply personal, often religious beliefs.

"I think some of my male colleagues didn't and don't see [abortion] as a major factor [in 2022], but I think when campaigns had women on their [campaign] teams, women at the table, I think those candidates handled and messaged the issue better,” said Amanda Iovino, a Republican pollster who worked on Youngkin’s 2021 campaign. She cited other successful anti-abortion rights candidates, including Rep.-elect Jen Kiggans (R-Va.) and Nevada’s Gov.-elect Joe Lombardo, as well as Youngkin.

“They got that it was going to be a factor, and they needed to figure out a way to respond,” she continued. "Abortion has always been an Achilles heel for Republicans talking to independent women. It's really tricky … but with good candidates who are trained well, who know how to talk about this, I think we can still thread the needle.”

Alice Miranda Ollstein and Zach Montellaro contributed to this report.

----------------------------------------

By: Elena Schneider and Holly Otterbein

Title: ‘THE central issue’: How the fall of Roe v. Wade shook the 2022 election

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/2022/12/19/dobbs-2022-election-abortion-00074426

Published Date: Mon, 19 Dec 2022 04:30:00 EST

Did you miss our previous article...

https://consumernewsnetwork.com/politics-us/a-common-theory-of-the-millennial-cringe