NEW YORK — David Shor and Sean McElwee were late, having come half-cocked from the Dissent Magazine issue release party earlier in the afternoon — “We’re socialists,” McElwee said with a shrug by way of explanation — and took their seats outside a dive bar on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, asking the bartender to bring two of whatever his most popular cocktail was. They downed those, clear concoctions that looked like headaches in a glass, then asked him to come back with the second most popular cocktail.

It was a hot afternoon in the summer of 2021, and they were in a good mood. In Louisiana, a few weeks prior, a congressional candidate backed by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and her allies had gone down to defeat. In Virginia, Clintonite fundraiser Terry McAuliffe had just beaten a primary opponent backed by the Sunrise Movement and the Working Families Party. The left flank of the Democratic Party, once seen as laying siege to the party establishment, was in retreat. In Ohio, the duo’s polling showed that progressive favorite Nina Turner looked set to lose, too.

The good feeling didn’t last, of course — McAuliffe ended up losing the governorship to a Republican — but even in the moment their glee seemed surprising. Shor, wearing dark, John Lennonesque sunglasses, keeps a red rose at the end of his Twitter bio, proof of a commitment to democratic socialism. He is the kind of person who, midway into his first cocktail, says, “I don’t want to sound insufferable, but I wake up every morning thinking about how I can reduce poverty, how I can reduce suffering.”

McElwee, who looks and dresses like an 8-year-old boy inflated to adult size, is the activist who almost singlehandedly made abolishing Immigration and Customs Enforcement a litmus test for ambitious Democratic politicians by relentlessly tweeting about it and demanding answers from elected officials. The happy hours he began hosting at a basement bar in the East Village in the early days of the Trump era had become the go-to spot for a rising generation of lefty activists, journalists and candidates. Ocasio-Cortez herself used to stop by.

Back then, “Sean and Shor” were still mostly known only to the extremely online set and lefty political insiders. But in the years since, as a counterrevolution swept the Democratic Party, they have both become the avatars of a more pragmatic approach — they call it “popularism” — and also, for political professionals at least, kind of famous: There have been multiple New York Times profiles, podcast interviews and various think pieces devoted to their ideas, all of which led to vitriol directed at them from their former fellow travelers who fear that their critique — that the Democratic Party is too reliant on ultra-progressive voters from elite precincts — is nothing less than a betrayal of the basic principles of the party.

Their message has found an audience among establishment Dems. McElwee had advised the Joe Biden campaign during the 2020 campaign (something many on the left never forgave him for) and both are advising senior White House and Democratic congressional officials on polling and messaging. In the early days of the Biden era, when it still seemed like a progressive takeover of the party was around the corner, their insights had the frisson of dangerous knowledge, samizdat for leftists fearful that their own side had gone too far.

“Everybody wants politics to be this really inspiring thing,” Shor said as the sun set on Suffolk Street. “But politics in the real world is an endless series of terrible, emotionally unsatisfying tradeoffs.”

“And if you pretend it’s not,” he said, “then you are going to make bad choices, and when you make bad choices, children go hungry. I don’t want to be extreme, but I think all of us who work in politics, we’re all so privileged to do this, to have people pay us to do stuff we care about, and they are doing it because they hope we help the outcomes. Those hungry kids are counting on us to make the right fucking choices, and so we shouldn’t get drunk on self-expression.”

He took a swig of his cocktail.

“I’m not saying I am going to make the right choice a hundred percent of the time. But at least I am trying, and I feel like a lot of other people aren’t.”

But a lot of people who work in professional Democratic politics, and who just a few years ago thought that they were fighting the same battles as McElwee and Shor, are pretty sure they aren’t. They see the two as selling little more than the warmed-over centrism of the Clinton and Obama eras that led to lost Democratic vote share among working-class voters.

Fast forward a year, and shift the scene 200 miles to the south, and roughly three dozen young progressive politicians and political operatives gathered at the top floor of an event space above H Street in Washington, D.C., where floor-to-ceiling windows look out onto the Capitol. The occasion was something called “SoundCheck 2022,” billed as a “conversation about the future of the Democratic Party.”

The immediate future of the Democratic Party, of course, would be determined by the coming midterms, but fearing a wipeout in November, organizers billed it as a look beyond this year. McElwee and Shor weren’t mentioned (not explicitly, at least), but their project — to inch the Democratic Party closer toward the median, moderate voter — was brought up all the time, and torched.

These activists weren’t here for hard truths about how to eke out pragmatic wins. They wanted a full-throated dose of the kind of progressive, identitarian politics that McElwee and Shor worried were tanking their movement.

“Self-interested elites and corporations are using racism to divide the working class from each other,” said Heather McGhee, the board chair of the civil rights group Color of Change, as the attendees, mostly professional Hill staff and D.C. nonprofit workers, gathered fruit salad and coffee from the back of the room. “The core question is how do we act as political storytellers. Our biggest failure has been our inability to name a constant enemy.”

The problem, McGhee added, was that, unlike the Republicans, too many Democrats in Washington, especially white men, found it “dispositionally difficult” to fight on those terms. “We need to pick sides,” she said. “We need to be the skunk at the garden party. Righteous fights are necessary for how people understand the world.”

It is now three months since that gathering, and days away from a midterm that looks set to render a decisive verdict on the last two years of unified Democratic control. But within the party, even though everyone understands the stakes in the same way — that the GOP is increasingly anti-democratic and remains in thrall to a nationalist demagogue — there remains uncertainty about how best to combat it. Should Democrats accept the American electorate as it is, and adjust its messaging and policies accordingly, or is there out there a latent population of Democratic voters, just waiting to be energized by a thrillingly revolutionary message?

As the party prepares for another brutal presidential election year, as it struggles to find its identity in a fraught era, it is this question which it is asking itself, over and over again. Every debate the party will have between now and 2024, from who will lead it to what bills and initiatives they should push, will really be a version of this debate, the one at two cocktail parties 200 miles apart.

Nobody, not even Shor or McElwee, has a concise definition of their notion of “popularism,” but in essence what they call for is Democrats to recognize that large parts of their agenda — raising wages, raising taxes on the wealthy, legalizing marijuana and statehood for Washington D.C. — are very popular with a broad section of the overall electorate, and Democrats should run campaigns focused on those issues.

They also strongly believe that Democrats should not run on certain other issues that college-educated elite Democrats in particular care about — like addressing police violence, liberalizing immigration laws, implementing the Green New Deal and ensuring trans women can play on sports teams that match their gender identity.

The problem, however, is that Democrats are increasingly the party of college-educated coastal elites, and the people who staff Democratic campaigns, government offices and policy shops are even more coastal and affluent and elite.

“People say, ‘Oh, Democrats are the party of eggheads, they don’t talk about values, they talk about issues’,” Shor said, doing his best imitation of a whiny Democrat. “The reason we don’t talk about values is that our values are really strange and weird. Only 20 percent of the electorate cares about our values. If they shared our values, they would be liberals.”

According to Shor, the distorted nature of our contemporary political moment makes what he is selling all the more important: There is the anti-Democratic threat from Trump, for one thing, and America’s out-of-balance political geography for another. A plurality of upper-income Democrats, even a large plurality, if it is centered on the coasts, doesn’t help the party win an Electoral College majority, or win the Senate seats in states like Ohio and Iowa they absolutely need if they hope to govern and pass laws in Congress.

To which, the anti-Popularists gathered in Washington, say, sure, OK — “What David is saying is kind of like if your financial advisor told you that you should make more money and spend less,” said Anat Shenker-Osorio, a communications consultant. Her point is that Democrats can’t simply run away from fights over race, sexuality and gender — or other "unpopular" topics like class and policing — when the other side is talking about them constantly. “What people hear about Democrats is not just what Democrats say. The other side has a very consistent message that they repeat over and over again — that Democratic cities are going to hell, that Joe Biden and Chuck Schumer are socialists. The idea that if we don’t talk about race, then the race conversation is just going to go away is nonsense. If we aren’t talking about justice, then we aren’t making sense.”

The problem with the popularists, those gathered in Washington say, is that what they are selling requires tossing overboard the very people the party is dedicated to helping, and asking key parts of the Democratic coalition, not just college-educated progressives but also working-class voters of color, to quiet down for a moment so that the concerns of white moderate swing voters can be attended to.

“David works very hard to steer the party toward a neoliberal way of doing things and towards a fight with large parts of our coalition,” said Adam Jentleson, one of the organizers of SoundCheck 2022 and a former aide to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid. “This inevitably means punching down, usually at Black and brown activists. Our theory is that if your strategy involves picking fights with the most active members of your coalition, then your strategy is flawed.”

If McElwee and Shor believe their own coastal cultural milieu has outsize power in policy debates, it is a belief they come to honestly. Shor, 31, is the child of two Israelis, a father who is a conservative rabbi and a mother who is a doctor and who was a socialist growing up. Keeping up with Israeli politics, Shor says, was a formative experience, and left him with a view that many American kids never develop: “The public can be bad. It is very important to manage public opinion.”

He grew up in Miami, one of the few white kids in his public school, and enrolled at Florida International University at the age of 13. As an undergraduate, he got into election forecasting, and built a model for the 2008 race that was as accurate as Nate Silver’s (“What Nate Silver is to anxious resistance libs, David Shor is to people that actually work in politics,” says McElwee.)

In the small world of political data scientists, Shor was regarded as something of a genius. By 20 he was working on the analytics team for the Obama reelection campaign. Friends and former colleagues say they persuaded him to cultivate the air of a young prodigy, that if he appeared at meetings with stuffy political types wearing a black T-shirt and didn’t say much, that it helped create a mysterious aura around him and gave their ideas more heft.

Having been too young for college, it is now almost as if he is making up for lost time. A fan of electronic dance music, he buys concert tickets in bulk, and distributes the excess to whatever friends happen to be available that night, keeping track of it all on a spreadsheet.

McElwee, 30, grew up in an evangelical family in the town of Ledyard, Connecticut, near New London. His first political engagement was witnessing fights over keeping the local naval base open. He moved to New York to attend King’s College, a school founded by the Campus Crusade for Christ, a school he chose only because he saw an advertisement for it in World, the evangelical magazine and the only magazine his family subscribed to.

McElwee was, at the time, what he calls “a rebellion Libertarian,” one who interned at the Reason Foundation and at Fox Business Network, but he would go home to his rural, working-class area of Connecticut, where he saw friends whose mothers were addicted to methadone and where he came to realize that libertarianism didn’t address the scope of society’s problems, nor did it allow for how the circumstances of someone’s birth could affect their life path.

McElwee got a job at Demos, a left-wing think tank in New York, and had the idea of having the city’s lefties get together every Thursday because having productive conversations about politics over Twitter was becoming impossible and because, he once told me, “I fucking hate books.”

“The world is zero-sum,” he said when I interviewed him for my own book about the ascendant left in the Trump era. “I don’t like knowledge that you can find in a book. I like knowledge that you can’t find in a book. After college you shouldn’t read a book, you should try to gain power.”

He met Shor at a happy hour he was hosting just after the 2016 election, at a moment when the data world was abuzz with Cambridge Analytica’s claims to have used “influence operations” on social media to swing the election to Donald Trump. “Either they are completely full of shit,” Shor told McElwee. “Or they are going to jail.” (No one actually went to jail. Cambridge Analytica did file for bankruptcy, though, and Facebook, whose customer data was mined, paid hundreds of millions of dollars in fines.)

Their T-shirts and tattered clothes and studied air of nonchalance notwithstanding, the two have worked to get to this point, cultivating relationships on Capitol Hill, speaking at great length with the political reporters and podcasters who help shape Democratic opinion and, in Shor’s case at least, getting into seemingly dayslong battles on Twitter with detractors.

They were both initially seen as unimpeachably progressive, even boundary-pushing in their leftism. But eventually the two came to realize that they seemed to know something that the rest of their comrades on the left didn’t — and that the larger progressive world of think tanks, advocacy organizations and nonprofits was willfully ignoring: that the electorate was far more moderate than the people in their circles imagined it to be, and that progressives were hurting their cause in the long run by ignoring that fact. It was the kind of thing that no one ever talked about when presenting PowerPoints to Democratic power brokers or to activist groups or coastal liberal donors, all of whom wanted to hear that the public was with them.

The whole polling industry complex was based on this delusion, and data geeks were selling it to the advocacy organizations and to their donors, who were lapping up confirmation of what they wanted to hear, even if it wasn’t backed up by the numbers.

Shor, whose expertise is not just election forecasting but message testing, pointed out that back in 2016, the Hillary Clinton campaign unveiled an ad that featured girls looking into a mirror while Donald Trump’s sexist remarks about women — “A person who is flat-chested is very hard to be a 10” — played. The ad thrilled college-educated voters and was a sensation online, but according to his research, actually made people who saw it want to vote against Clinton. “Donald Trump is talking about jobs and immigration and you are just trying to guilt-trip me into all of this liberal bullshit?” By contrast, they tested every single ad in the 2020 campaign, and the one that performed best with voters by far was one where a former soldier in Iraq talked about how Biden worked with Republicans and Democrats to secure mine-resistant vehicles for troops.

“I’ve had a lot of people in my industry say they are glad that someone is finally saying this stuff publicly, because if you actually do public opinion research, like if you go and dig into this, you realize that the public holds lots of retrograde beliefs, but there are actually not a lot of incentives to say this publicly.”

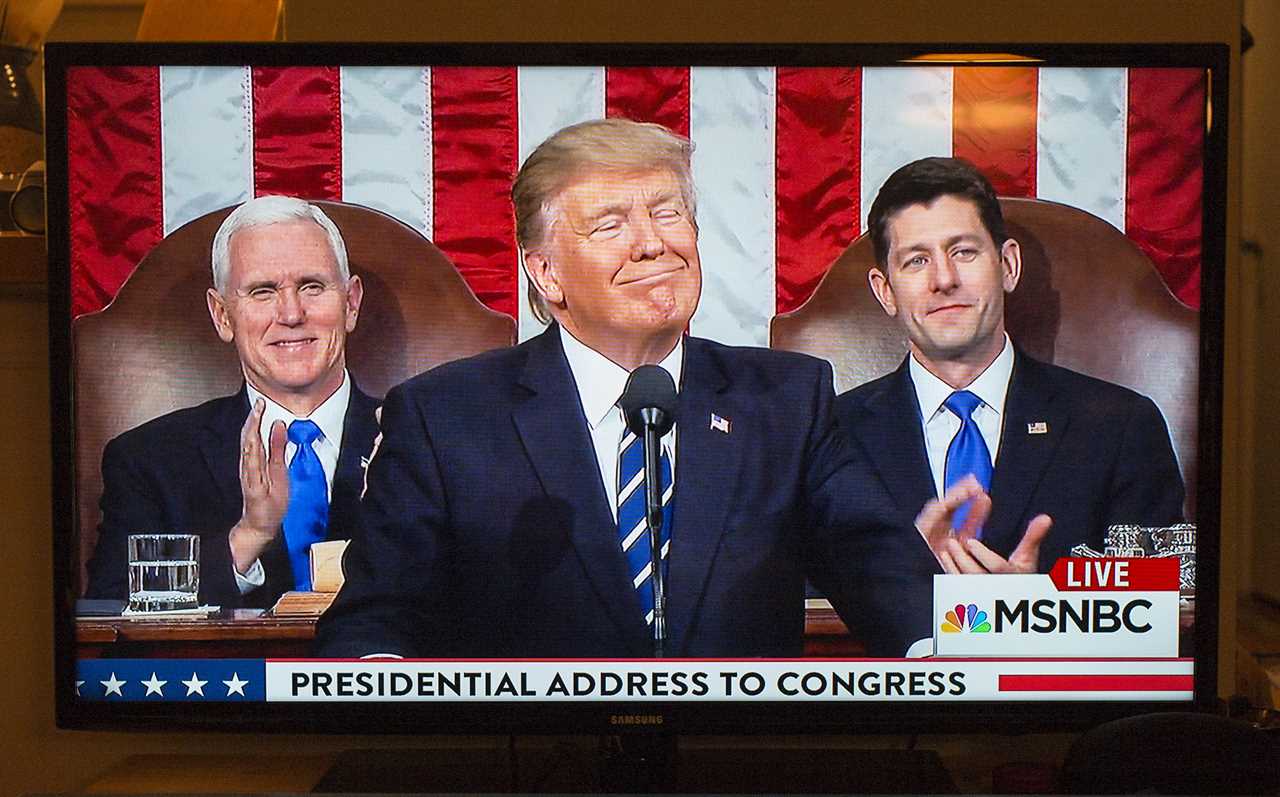

Shor speaks in a voice that can sound like a pleading whisper, and even at a party he tends to say the same thing to his friends that he does to a reporter. And he likes to be at parties; Shor’s home on the Lower East Side of Manhattan serves as a regular spot for like-minded pols to raise money, and for his fellow millennial hipster political types to gather until the small hours of the morning. At one party last summer, as a rerun of the 2012 vice presidential debate between Paul Ryan and Joe Biden played on a flat-screen TV and a layer of vape smoke settled over his sparsely furnished loft, Shor was unable to keep his brain from whirring about how to improve Democratic vote share.

“I just think the Democrats should do popular things,” he said to a handful of political operatives and organizers sipping on Kirkland-brand hard seltzer from his fridge.

“If you look at some of the most popular policies in the United States, sure, there’s some correlation with ideology. But some of the most popular things, like wealth taxes, prescription drug negotiation, the Loan Shark Prevention Act — these are things that the public wants, and they are not moderate proposals, but you never hear activists talk about it. I mean, I get that the left has to spend all this time attacking the DNC as corrupt or whatever, but seriously, they should be attacked for not pushing marijuana legalization or for keeping our credit card interest rates so high. Just a little bit of message discipline would be so much more productive. There is no amount of pressure that is going to make Democrats create Medicare for All, because the public doesn’t want it.”

A pollster showed up with a bottle of red wine, popped the cork and started drinking it out of the bottle. (When my face betrayed surprise, he apologized for his rudeness and asked if I wanted a sip.) McElwee started to stress because the ice he had ordered from Drizly hadn’t yet arrived. “Maybe it’s because you tried to abolish it,” someone said. McElwee seemed to not get it, and began listing all the leftists he has now alienated, and who, he says, write hit pieces about him in their small journals or talk smack about him on their podcasts.

“In their defense, I am kind of a sell-out,” he said.

Those in Shor’s circle have the zeal of the converted. Most, like him, spent the past few years firmly on the party’s left, and started drifting away from that tentpole after the 2018 election, which saw Republicans increase their Senate majority in a Democratic wave year, and the 2020 election, which again revealed, despite a Democratic victory at the top of the ticket, that the forces arrayed against them were deeper than many first realized.

“There is this whole ivory tower left, they have no idea what they are talking about,” said Rabyaah Althai, a Yemeni-American community organizer and political consultant who was a surrogate for Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020. “I am basically a class reductionist. I am as left as left can get, but still, I want to win.”

Over in another corner, another operative, one who works in digital strategy and who asked that his name not be used, was explaining his own evolution.

“People get into politics to bring about progressive change, but once you start really working on elections, even in a city like New York you realize that the shit someone who went to Swarthmore and goes to DSA meetings says on Twitter is not what voters think. In 2016, there was this feeling that you could just mobilize your way into Democratic landslides, but anyone working in politics can tell you that persuasion is the whole ballgame.”

“Look around, you won’t see anyone wearing an Abolish ICE T-shirt here,” said one partygoer when I asked about the different vibe here from the happy hours of a few years ago.

I pointed out one guy who in fact was in an Abolish ICE T-shirt.

“Yeah, he’s doing it ironically.”

As McElwee and Shor see it, liberals spend too much time carping on things like Fox News, Facebook and even voting restrictions. Republicans aren’t cheating, and conservatives aren’t brainwashed; they are just conservative. Americans, as Shor put it, “really fucking hate taxes,” and so there is a hard limit to how much of a Nordic-style social democracy the country can become. Leftists in the policy world have turned against means-testing, believing that universal programs like Social Security have more durability, but as Shor tells it, that means wasting precious tax dollars on giving benefits to lawyers and doctors instead of to the poor who really need them.

“The more you represent liberal elites, the more you will turn off non-college voters of all types,” he told me. And the slow creep of working-class voters of color into the Republican camp “is not something people saw coming, and I am not even sure how you deal with it. How do you get a bunch of people who are conservative to vote for the Democratic Party, especially if what you are pushing is ideological polarization?”

“I wish they would just come join us! This is popular stuff!” said Leah Hunt-Hendrix out on the patio sneaking out during one of the Q-and-A sessions at SoundCheck 2022.

The organizers of the event said that it was meant as a gathering of “The Offline Left,” and was meant to show the seriousness of purpose behind those gathered, many of whom, unlike their counterparts in New York, worked in or around the government. The event stretched on most of the day, a bagel brunch gradually giving way to hors d’oeuvres and wine, but the vibe was more earnest, a little brainier, and, even in the evening, far less boozy.

Hunt-Hendrix was, along with Jentleson, one of the organizers of the event. The granddaughter of Texas oil tycoon H.L. Hunt, she became one of the founders of Occupy Wall Street after asking herself, as she once told Salon, “What do you do when you realize that your history is the history of exploitation? That your lifestyle is depends on a system that you now see is unjust?" After Trump won, she co-founded Way to Win, which convenes Democratic donors to give money to grassroots groups in swing states and districts.

On the fundamental problem facing the Democratic Party — how to appeal to a white working class that was once the bedrock of the party but has been shifting to the Republican camp — everyone is in agreement. Hunt-Hendrix kicked off the confab by reading from a memo prepared by House GOP member Jim Banks for his caucus, titled “Cementing GOP as the Working Class Party,” which laid out how the fact that college professors, marketing professionals and bankers were now mostly Democrats opened up a massive area of opportunity for Republicans if they reoriented their agenda toward the working class.

“It’s like that Internet meme, ‘Worst Person You Know Made a Good Point’,” Hunt-Hendrix told the crowd.

The solution, as she and her cohort see it, isn’t popularism, but what they call “inclusive populism.” The idea of inclusive populism is to rally working-class voters of all stripes against corporations and political and economic elites, and name attempts at racial and gender divisiveness as diversionary tactics employed by the 1 percent to entrench their money and power. Rather than accept the framing of the right and pledge to end Big Government or reform welfare — or, as Biden put it, “The answer is to fund the police” — inclusive populists say that that what works is messages that call out Republican attacks as a trick to get working class people fighting with one another while they enrich themselves.

But before they can fight the Republicans, they first have to win the debate inside their own party. The popularists, as Hunt-Hendrix sees it, say “we are spending too much time on cultural issues rather than ones that poll well. But my argument is that they are the ones who keep talking about cultural issues. You won’t hear anyone here talking about defunding the police” — she gestured backed toward the symposium — "but they keep bringing it up. And besides, when the right criticizes our side about something, the solution shouldn’t be ‘let’s turn around and kick in the face our own activists.’ The solution should be we should go after the people that are the problem. I want us to be a party that punches back and doesn’t take the bait, and they keep on taking the bait.”

As the Inclusive Populists tell it, the Democratic Party started to go awry during the Obama years. His was a style and a rhetoric that let all Americans see themselves in the story he would tell about the country; allowed voters to place themselves in the grand sweep of the nation’s progress from the revolution, through waves of immigration, westward expansion and social justice movements, culminating in his election as a path-breaking president.

All of which left room open for someone who could put together a coherent story for people looking for someone to explain why, if all that inspiring stuff was true, everything seemed to be falling apart in the country, as inequality increased, housing, medical care and the cost of living skyrocketed, and ever larger swaths of the country were left behind in the global economy.

Inconveniently for every Democrat in America right now, the person who did figure it out wasn’t a populist like Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren. It was Donald Trump. And in a way, the whole fight between the popularists and the inclusives is about how to grab the microphone and that argument — their argument — back from the elderly white nationalist celebrity who took it over.

Jonathan Smucker, a Berkeley Ph.D. student in sociology and a political consultant in western Pennsylvania, told the group gathered at SoundCheck that leftists can actually replicate what Trump did, tapping into economic anxiety, but redirect it without the racist comments. By going after the media, Hollywood, the academy and Democrats, Trump makes it seem as if he, a celebrity New York billionaire, is punching up. And importantly, by going after leaders of his own party, like “Old Crow” McConnell and the Bushes, he gains outsider cred.

Democrats, to be successful, have to learn to do the same, and “call out the corporate wing of the Democratic Party for failing to take on Wall Street and the corporations, failing to get money out of politics and failing to stand up and fight for every day working people,” Smucker told the group.

And the key is to counter the Republicans’ Trumpian rhetoric by calling it out whenever possible as a distraction that keeps working people fighting among themselves instead of taking the fight to the actual people in power. Their shorthand for how to do this is “race-class narrative” — a political framing that, as one creator told me, argues that “racism is a weapon of the rich that pits us against each other. And so the threat we face is not from other racial groups, it is from the power elites.”

As a communications tactic, this is the brainchild of Anat Shenker-Osorio; the Berkeley Law professor Ian Haney Lopez; and McGhee, of Color of Change. The group actually tested its hypothesis by convening randomized controlled trials with different sets of voters to find out what works. The idea is to provide data so that Democratic operatives and ad makers are all using the same strategy, with the notion that once words get repeated often enough, like “Fight for $15” or “Love is Love,” they get seared into voters’ minds as common sense, and unobjectionable. What they found was that voters responded to active formulations that tied raising revenues and raising wages to the boogeyman of wealthy corporations and business leaders refusing to pay their fair share. Their ads don’t show the president getting better battle gear for soldiers; they show young, mostly white men in suits lighting cigars with dollar bills and letting wads of cash just blow away in the wind.

Their data found that by giving voters a binary choice — you can have higher wages or rich corporations can keep the money; you can have better housing and schools or the wealthy can keep the money for themselves — increases their vote by more than 30 percent among persuadable voters.

Their belief is that Republicans have been using race and gender and sexuality to attack Democrats for the past half-century. If Democrats give in to white and straight and male anxieties around these topics, not only are they abandoning their base — something that is much harder to do in the diverse America of 2022 than it was when Bill Clinton tried it — but they are losing vote share. And so while the popularists pride themselves on their ability to properly take the temperature of the electorate, the inclusive populists, backed by race-class narrative research, say they can better bring the pot to a boil.

Somewhere at the core of their debate is a long-running political argument on the left: To win, do you need to persuade the persuadables, or find new ways to excite people and get them to show up?

The popularists, the inclusives claim, are too caught up in finding and catering to a median voter who simply doesn’t exist. And they exhibit far too much certainty that they know what people really care about.

The popularity and salience of issues actually changes all the time, they note. Witness the titanic shifts that same-sex marriage has undergone, or the reversal in feelings toward Russia that the parties engaged in between the 2012 election and the 2016 one. Rather than calculate their positions toward whatever is most poll-approved, successful politicians are authentic, and show that they have the same enemies as their voters. Do that, and voters will forgive you all sorts of radical policy ideas. Jentleson points out that Shor himself was a Bernie Sanders fan — despite Sanders’ embrace of any number of nonpopularist ideas.

“The reason David likes Bernie is because Bernie was so popular, and so the question is why?” Jentleson said. “Part of the point we are trying to make is that his is a worldview that resonates with people. It wasn’t just his policy prescriptions, but it was, for lack of a better word, his vibe, that people thought was authentic.”

A common criticism of the popularists from the inclusive populists is that what they are selling is really little more than warmed-over Clintonian centrism. Leftists like to bait Shor and McElwee on Twitter by asking them what they would have advised Democrats to do about same-sex marriage in 2008, or the Iraq War in 2003.

The current version of those issues is something like Black Lives Matter — a cause that alienates some white working-class voters, but that may also have the right mix of committed grassroots activists and moral power to foster genuine political change.

It’s the exact kind of possibility they worry Shor wants to close off. And when they really want to twist the knife, they speculate that the “median voter” that the Popularists like to invoke is more like an invented mouthpiece for the popularists’ true views.

“David Shor and his crowd could never say that Black Lives Matter activists need to shut up,” said Shenker-Osorio. “He knows what would happen if he did. So he says that ‘Oh, yeah, a bunch of well-educated white people who live in coastal cities need to watch what they say.’ But it amounts to the same thing.”

McElwee doesn’t see it that way. “If you look at David’s and my specific track record, we do a lot of work in the progressive space to make the world a better place,” he said in response. “My staff is 50 percent people of color. My stated preference is for much more liberalized immigration laws and fewer people serving shorter sentences, but I believe the way to achieve those goals is having Democrats win elections. And I think it is really bad for marginalized groups when they are represented by Republicans instead of by Democrats, even if those Democrats talk about those issues in ways that people who live in cities and have advanced degrees don’t necessarily agree with. If you look at the revealed preferences of marginalized groups and who they vote for, it tends to not be a lot of left-wing bomb throwers.”

Shor did like Sanders in 2016, but found himself shifting in 2020. In 2016, Sanders nearly won the nomination by, as Shor tells it, talking about popular things like raising wages and taxing the wealthy. By 2020, he and Elizabeth Warren were chasing after the same small minority of activists, and turning off the rest of the electorate.

“In 2016, Bernie Sanders did well because he was talking about popular things,” Shor said. “He could talk about health care, and he could talk about legalizing marijuana, but he didn’t say he was only going to allow Black people to sell weed, which is a real fucking thing he said in a debate!”

“Oh my god, these debates. I can’t tell you how painful they were to me,” he said about the 2020 primaries. “It was a fucking parody. Like, oh, we are going to talk about marijuana legalization, which is super-popular, but only in the weirdest, most racialized way possible. It was an Olympics to embrace unpopular ideas. Here were legitimate candidates with decent chances of winning the presidency and they were talking about reparations and legalizing opioids!”

The leftists who came of political age over the past several years, which nearly saw a socialist twice win the Democratic nomination and avowed DSA members get elected to Congress, don’t know how good they have it.

“These people are spoiled. I get really annoyed. I’ve been a socialist for years and all these people who are, you know, stans of Bernie Sanders or whatever, they don’t know what vanguardism is,” Shor said. They’re high on this idea of revolution, as if there is massive popular support for socialism. And the reality is that things are better than they used to be, but most of the public holds reactionary views.”

For two people who’ve sold themselves as the future of the party, Shor and McElwee say the key to the party’s success actually lies somewhere in its past, when Democratic politicians knew how to talk to voters. Shor and McElwee went back and started watching old debates and convention speeches, and couldn’t believe what they were seeing. The people on stage were deploying practically an entirely different language, one that made sense to real people instead of interest groups and activist organizations.

The older generation of politicians, like Sanders, Bill Clinton and Joe Biden, had to win in an era when the electorate was less polarized — Shor pointed out that Biden won Delaware by 20 points in the same year that Ronald Reagan carried the state by 20 — and so knew how to talk to different audiences, and how to persuade people who may disagree with them about something.

On the other hand, any casual viewers not steeped in the progressive discourse of the moment would look at the 2020 Democratic National Convention for just a few minutes and pick up on the cues that this was not a party for them.

“Your job as a left-wing person is to figure out how to take your ideas and like, trick them and mold them into something that the median voter could support,” Shor said.

He and McElwee asked for whatever the third most popular cocktail was and then ordered that. It came with little flowers on top. “Every Democrat needs to ask themselves if what they are doing is increasing education polarization or decreasing polarization, because if we don’t figure that out we are never going to win the Senate and we are never going to win the Electoral College.”

“2012 is the last time that an older generation of political operatives was in charge of Democratic campaigns,” he added. “It’s all millennials now, and you can see it in how they conduct their communication. It used to be about persuading people, and now it is about trying not to piss off any activist groups, and it gets to the point where you can’t say anything without having consultants review it for months to make sure it doesn’t offend anyone, and it gets to the point where people don’t even hear what you are trying to communicate.”

Nowadays, he says, Democratic politicians have come to be so reliant on online fundraising that they have realized that the steps to political advancement begin with saying something spicy on TV or on the Senate floor, hoping it appeals to Twitter users with large platforms, watch the retweets roll in, get booked on MSNBC and then get profiled by a lefty journalist in a major magazine, and then watch the online funds flow — never mind that most voters aren’t watching cable news, or on Twitter, or reading long magazine profiles.

It's possible, too, that a challenge for both sides of this Democratic debate is that it’s hard for the party to grapple with how far the left has come. McElwee first became known helping to primary moderate Democratic incumbents, but that tactic has no place at a time when Democrats are in power and trying hard to hold on.

Back in the Obama years, the party wasn’t far enough to the left, and it hurt them with voters, McElwee’s and Shor’s research found. Had Obama gone further with the Affordable Care Act, or passed a bigger stimulus, he might have staved off the Tea Party wave.

Now, though, the party is plenty left, and American policy has shifted sharply. The left has moved the needle on one issue after another, from same-sex marriage to marijuana to the size and role of the federal government, and conservatives are forced to rely on courts to reverse their gains.

Progressives, in other words, have won battle after battle for the soul of the Democratic Party. But instead of consolidating their gains and taking the fight to the Republicans, they keep waging war, McElwee says, with their own side. “The left doesn’t know how to win with dignity and grace. Do you know how many cryptocommunists are now working for the Biden administration? How many former Bernie Sanders staffers who are pretty f---ing deep in the White House’s policy nexus? The revolutionary socialist phase has kind of faded for the left,” said McElwee. “But the flip side of that is that a lot of those people have infiltrated to the highest levels of Democratic politics.”

----------------------------------------

By: David Freedlander

Title: The Booze-Soaked Tribal War Inside the Democratic Party

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/11/04/cocktail-parties-that-could-define-democrats-00064560

Published Date: Fri, 04 Nov 2022 03:30:00 EST