It is often customary, when writing about a person, to open with an image or an anecdote that illustrates something about them. When I sat down to write this story, which is about President Joe Biden, and particularly his influence on culture, I could think of very few. I tried to manufacture some, watching videos of his inauguration and subsequent speeches; looking at pictures of him in the Oval Office and reading about the art he had chosen for the White House; considering the Bidens’ Christmas decorations; even asking people I’d interviewed what cultural moments of his first year in the presidency had stuck with them. Yet everything I came up with felt forced.

The truth of the matter is that the first year of Biden’s presidency has been marked by a certain absence of striking symbolic images — an aesthetic lack.

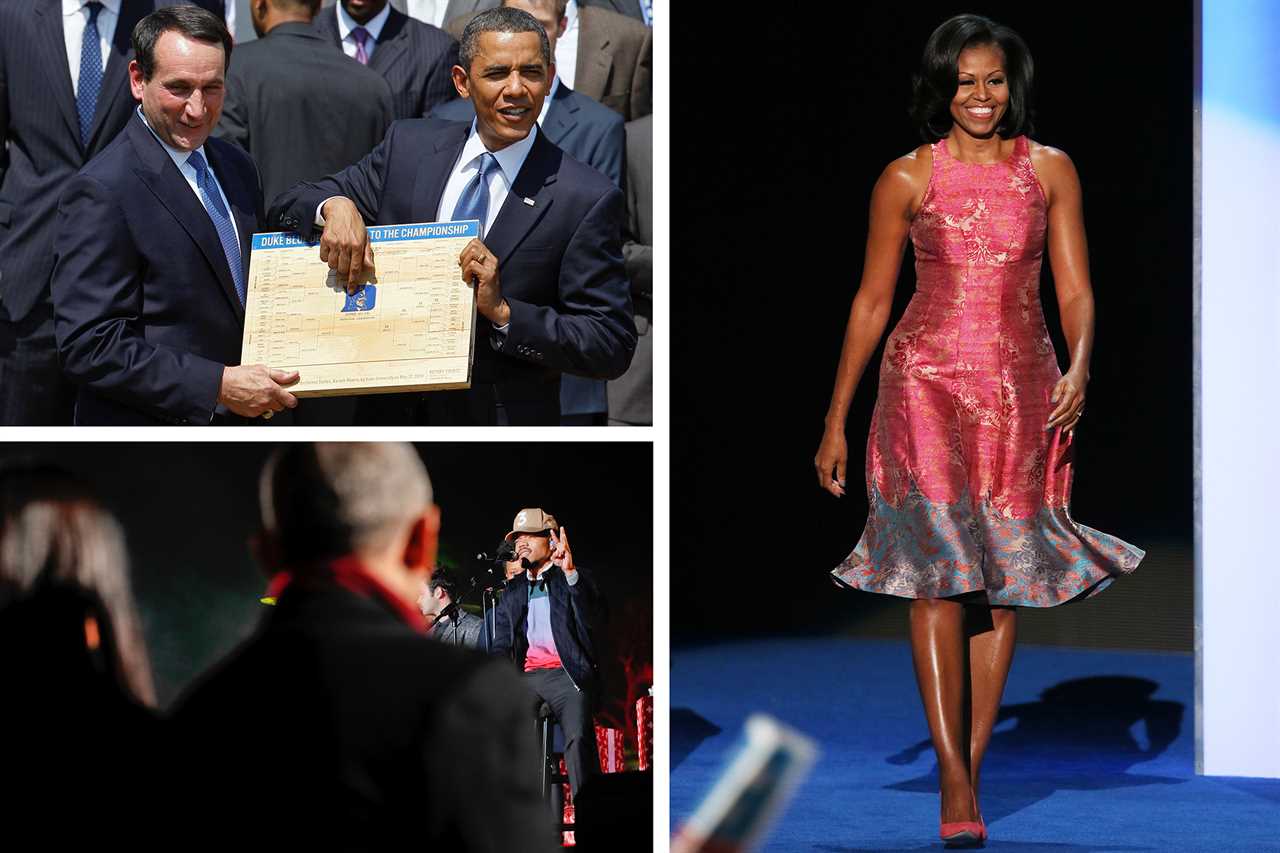

This absence is particularly noticeable because the last two presidents reinforced the idea of the American president as a cultural-tastemaker-in-chief, albeit in very different ways. Barack Obama for years has put out year-end lists of his favorite contemporary fiction, music, movies and TV shows. He made a public March Madness bracket every year in office. As first lady, Michelle Obama became a style icon; her tastes were as closely followed as his. As Ta-Nehisi Coates documents in his essay “My President Was Black,” the Obamas invited to the White House musicians ranging from Bob Dylan to Tony Bennett to De La Soul; they had Chance the Rapper and Frank Ocean at a state dinner, and invited the rapper Common to perform over the objections of right-wing media.

On the heels of this, dizzyingly, Donald Trump sought to legally enforce neoclassical design in federal buildings and build a “National Garden of American Heroes” that would have statuified Bob Hope and Ben Franklin. First Lady Melania Trump’s Christmas décor, which included two long lines of faux, blood-red trees, earned mockery for its almost garish horror. There were heavy-handed symbols, employed both by supporters and detractors of his politics: the MAGA hats, the iconic swoop of hair. There was the flashy opulence of Mar-a-Lago and the red-white-and-blue of his raucous rallies. As Dan Zak observed in the Washington Post, Trump’s personal aesthetic — “the gold, the braggadocio, the huckster superlatives, the reality-TV staging, the all-encompassing obsession with his surname” — blended and clashed with the traditional norms of the presidency. But all of it was, anyway, striking.

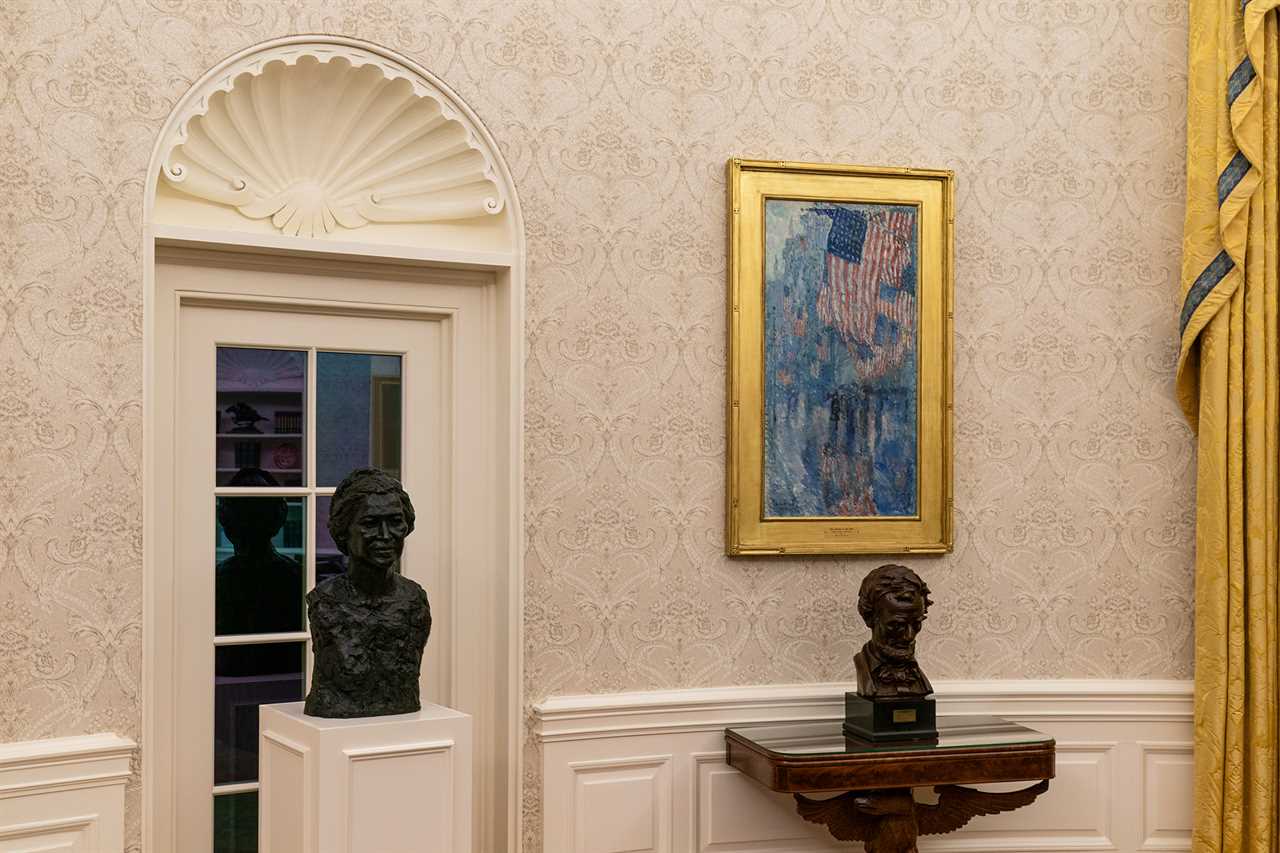

Biden, meanwhile, doesn’t make a year-end Spotify playlist (one wonders: does he even use Spotify?). His inauguration was quiet. His Christmas decorations are not in any way notable. Perhaps his most defining fashion choice, a vestige of the image cultivated by the Onion during his VP years, is wearing aviator sunglasses, looking like a rockstar in retirement. He doesn’t generate any controversy with his decorative decisions. His most quintessential piece of Oval Office art, in my mind, is a 1917 painting he selected by Childe Hassam titled “The Avenue in the Rain.” Stars and stripes soaked in oil-painted rain — it’s easy-visualizing, a combination of impressionism and Americana. It’s also sentimental. Critic Glenn Adamson, just after Biden’s inauguration, referred to the painting’s “aesthetics of reassurance” amid our much-invoked challenging times. Who can reasonably object to a president’s choosing a painting like that? And who can really claim to find it interesting?

Steven Heller, co-chair of MFA Design Department at the School of Visual Arts, described Biden’s aesthetics, in a word, as “invisible.” “Biden,” Heller says, “is this kind of white fox who blends into this winter of our discontent.”

This is all, in a way, to be expected. It affirms Biden’s political messaging — the back-to-normalcy he promoted during the campaign, the implicit promise that he would be a boring president you wouldn’t have to think about, and the overall return to a man in the White House who resembles a 20th-century politician more than one who’s governing in the 21st. Perhaps especially during a pandemic, the fact that there is a certain absence of culture and images from the first year of his presidency hardly comes as a shock.

Still, it marks a shift — one that ultimately might say less about Biden and his administration, and more about the kinds of cultural icons Americans want today. In a country that’s increasingly divided, as well as increasingly heterogenous, and in a media landscape that’s increasingly fragmented, who is really looking toward the president for culture? Especially toward a president who is fashioning himself, more or less, as just a president.

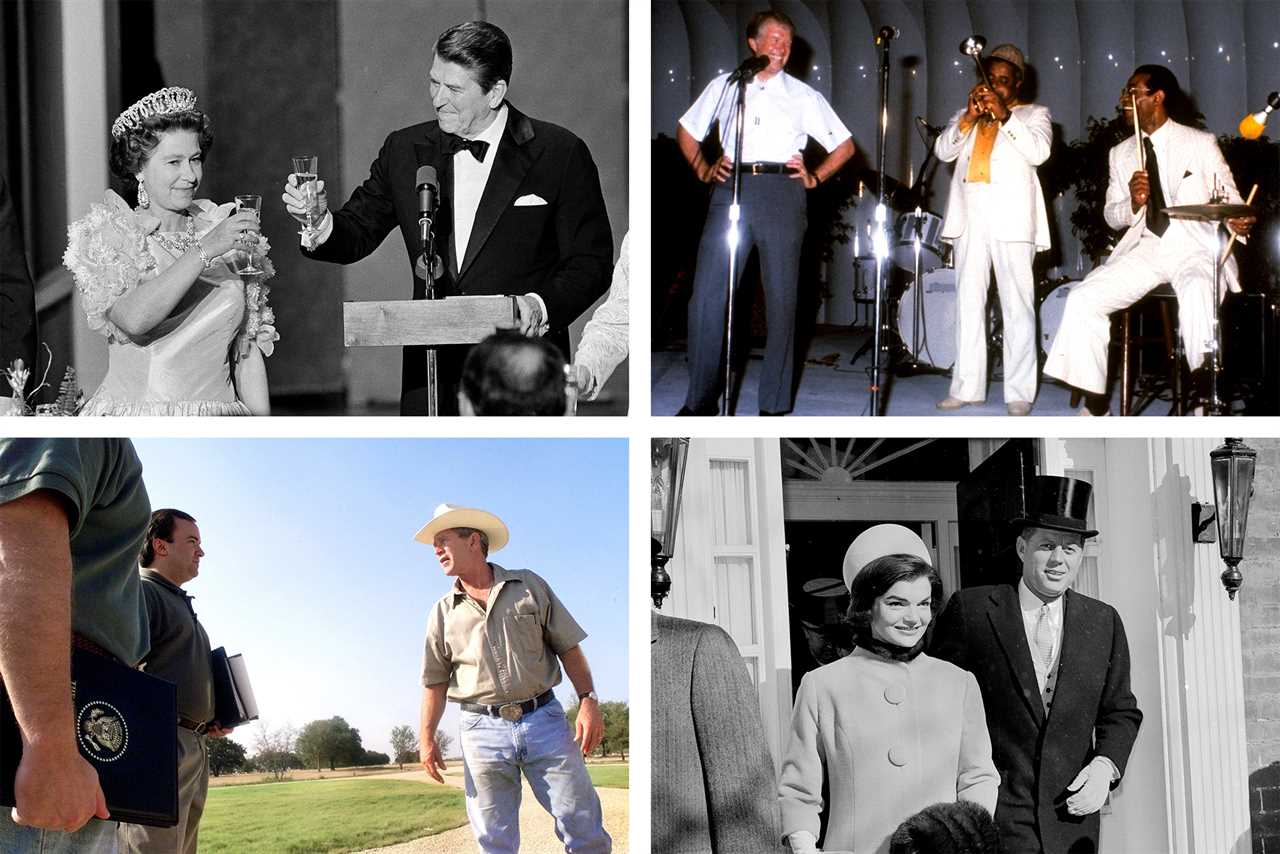

The most famous modern example of president-as-tastemaker is John F. Kennedy, alongside his wife, Jacqueline Onassis Kennedy. “I think a lot of our understanding of the presidency starts with Kennedys,” says Courtney Travers, a scholar at Vanderbilt who studies, among other things, first ladies and fashion. They embraced the visual elements of their respective roles, and the result was the White House as Camelot, the shorthand that survives in our lexicon to this day and, tellingly, refers to a mythical kingdom. “Discussions about presidential aesthetics are interesting in the American context,” says Cara Finnegan, a professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and author of the book Photographic Presidents: Making History from Daguerreotype to Digital. “Because with the lack of a monarchy, it’s really about: Where do you get your pageantry?”

Pageantry is just parties and decorations, in one sense, but, in another, it’s a significant display of American culture, national identity and nationalism itself — a message to the country and to the world about U.S. priorities and values at any given time in history. “Most presidents have held arts and culture in incredibly high regard, and as a temporary resident of this exquisite mansion that we call the White House, presidents believe it is a duty to host a 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue and to showcase the best of America, the diversity of our talent in this great nation,” says Capricia Penavic Marshall, who served as social secretary for Bill Clinton and chief of protocol for Obama. Marshall described some of the ways different presidents and first ladies occupied this role: The Reagans, she said, amped up state dinners, hosting them every month. The Clintons loved jazz, and so organized jazz nights. Rosalynn Carter, knowing that her husband was experiencing loneliness while in office, organized in-house entertainment that was televised to the American public. “It brought in a bit of joy, but it also made this art accessible. It allowed us to watch the president watching this,” Marshall says.

Even George W. Bush, a scion of the political elite, fashioned a certain cultural aesthetic while in office, positioning himself as a swaggering Texas cowboy, a phony persona well-tailored to the post-9/11 era.

One obvious limitation to the Bidens’ ability to shape White House culture has been the pandemic, which has restricted both large-scale entertaining and performances. His inauguration, coming just after the rollout of the first vaccines, had a smaller-than-usual attendance. Biden has yet to hold a state dinner, and the White House canceled its holiday parties this past year. The Bidens have still had other, mostly smaller-scale ceremonies and receptions, but even as it has become possible to entertain more normally, massive White House fetes are perhaps not the appropriate mode for the leader of a country ravaged by illness and death. (Obama, meanwhile, was widely criticized for the celebrity-filled 60th birthday party he hosted on Martha’s Vineyard in August, as the Delta strain was spreading.)

The Bidens’ aesthetic interventions necessarily have been quieter in nature — adjustments to décor that are more gestural than splashy. Marshall says that when she returned to the White House for a tour during the holiday season, she noticed a rehanging of some portraits of former first ladies outside the East Wing. “It might seem like a nothing-burger, but those first lady portraits were in places where no one saw them before,” she says, attributing the move to Jill Biden. Travers, of Vanderbilt, also notes that the current first lady’s sartorial choices have emphasized designers who prioritize sustainability or who have backgrounds in rural places and small towns.

Meanwhile, Biden’s Oval Office includes loads of representations — busts of César Chávez, Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr., for example, as well as what Finnegan calls the “wall of men.” Above the fireplace, she explains, presidents traditionally have hung a single painting or portrait, or just a few; they often take photos with foreign leaders sitting in front of the space. Biden, meanwhile, has hung five portraits, of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt. “These were people whose ideas were often in conflict, and so it’s a metaphorical way to point toward how they could work together instead of disagree,” Finnegan says. “But visually it’s so jarring, because anytime you see one of these pictures, there are five people standing behind whoever is there.” This feels very Biden: the visual aesthetics sacrificed, perhaps, to make an aspirational point about bipartisanship and disagreements being bridged.

On the whole, it’s all reading as very “normal,” as Washington Post critic Robin Givhan noted when she praised the White House Christmas decorations for their humble elegance. They were themed around the idea of “Gifts from the Heart,” and included a red bow over the entrance to the East Wing. The annual Gingerbread White House was transformed into a “gingerbread village” that included a school, hospital, grocery store, warehouse, police station and fire station. “Nothing feels overstuffed or overwhelming. The decorations don’t brag, and they’re generous in their gratitude,” Givhan wrote. She noted that the Bidens’ family photos, incorporated into the decorations, were pleasingly typical: “They are not Camelot. They aren’t regal. They look ordinary and ordinary is good enough. Ordinary, quite frankly, is miraculous.”

Implicit in this invocation of the ordinary is the comparison to something extraordinary. Or, the lingering ghost of the Trumps. Finnegan notes that presidents are almost always defined in terms of contrast with their predecessors: “So, Biden’s decorations are going to be compared to Melania’s scary wall of trees.”

It’s fair to ask: Does any of this really matter anymore? Are we really looking for a president to be a tastemaker in this moment? JFK has been blamed — perhaps unfairly — for single-handedly ending the long-standing fashion of men wearing hats after he took his off at his inaugural address. Jackie inspired fashions and even mannequins modeled after her. Obama still drives sales with his book lists, even in his post-presidency. Trump’s influence, meanwhile, has spawned an entire brand of conserative aesthetics; the MAGA hat and its offshoots now more or less dominate the GOP. But Obama and Trump are appealing to their political bases rather than shifting the norms of the wider public. Part of that has to do with political partisanship, but it also might say something about where the American public is generally looking for influence.

There is no monoculture anymore. Once-influential fashion magazines have dwindled in subscriptions and influence, or shuttered entirely. The media itself is ever-more fractured. More and more, people get their aesthetics straight from social media. Instagram influencers have a wider reach than senators, especially when it comes to culture. Perhaps the president and first lady are simply no longer icons of contemporary culture and taste.

Biden himself would be an unlikely figure to take that role, anyway. For one, he is simply old. There would be something disingenuous about an attempt to fashion himself as an influencer. He also has spent decades in American political life, and decades in a suit and tie. Trying too hard would come with its own risks; the aesthetics of liberal governance are at best hokey, and at worst appallingly embarrassing. In GQ, fashion writer Rachel Seville Tashjian dubbed the Biden inauguration — with its “America United” theme, ubiquitous “bipartisan” purple outfits and decidedly not edgy musical acts — “A Return to Corniness,” which, she noted, wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. “Corniness was the leading aesthetic of American political life before the Trump administration ushered in four years of camp, which differs in its total commitment to brash and vindictive bad taste,” she wrote. “Corniness is comforting, and decent, and old-fashioned.” But, as she also noted, there’s only so far corniness can take us; it represents a throwback to a concept of normalcy, and in particular, a shared sense of culture that no longer really exists.

Wherever it stems from — a combination of the lingering pandemic, general malaise and the Bidens’ own choices — this sense of a lack of a cultural figurehead in the White House can rankle at a time when the stakes of American politics are so high. “We need more,” says Heller, of the School of Visual Arts. “January 6 was a horrible, horrible moment in our collective history, but it’s going to be remembered because of that shaman. It’s going to be remembered because of the images that were put out of it. … It was a visual moment. There’s got to be something to counter that.”

Even if you don’t quite buy that presidential aesthetics can counter those forces, it still can feel like something is missing from American life — some sense of shared aesthetic discovery. Or perhaps simply pageantry, which we turn to presidents for, for better and worse. As one former Obama official said of the Biden White House, “It would be nice to see them get a little more experimental, to see more daring design, something more out of the box.”

----------------------------------------

By: Sophie Haigney

Title: The Bland Aesthetics of the Biden Presidency

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/01/30/biden-aesthetics-presidents-bland-00003265

Published Date: Sun, 30 Jan 2022 07:00:00 EST