For a stretch of time last year, the deaths seemed to keep coming in the Orleans Justice Center, New Orleans’ jail. In August, 46-year old Robert Rettman died from what the coroner’s office called “asphyxia due to hanging.” Before Rettman, there were 35-year-old Christian Freeman and 27-year-old Desmond Guild, both of whom collapsed suddenly in their cells, were rushed to the hospital and died. Freeman had fentanyl and a veterinary-grade sedative in his system; he also tested positive for Covid-19. Guild appears to have died from a blood clot.

These men are not alone. This month, Incarceration Transparency, a project out of the Loyola University New Orleans law school, released a database documenting 15 deaths at the Orleans Justice Center between 2014 and 2019. Only two other Louisiana jail facilities, both of which have larger incarcerated populations, had higher death counts. Almost all the Orleans Justice Center’s inmates are pre-trial, and many are jailed for nonviolent charges. “The fact is, so many people go in for traffic tickets, and don’t come out,” says Ursula Price, a longtime criminal justice reformer now serving as executive director of the New Orleans Workers’ Center for Racial Justice.

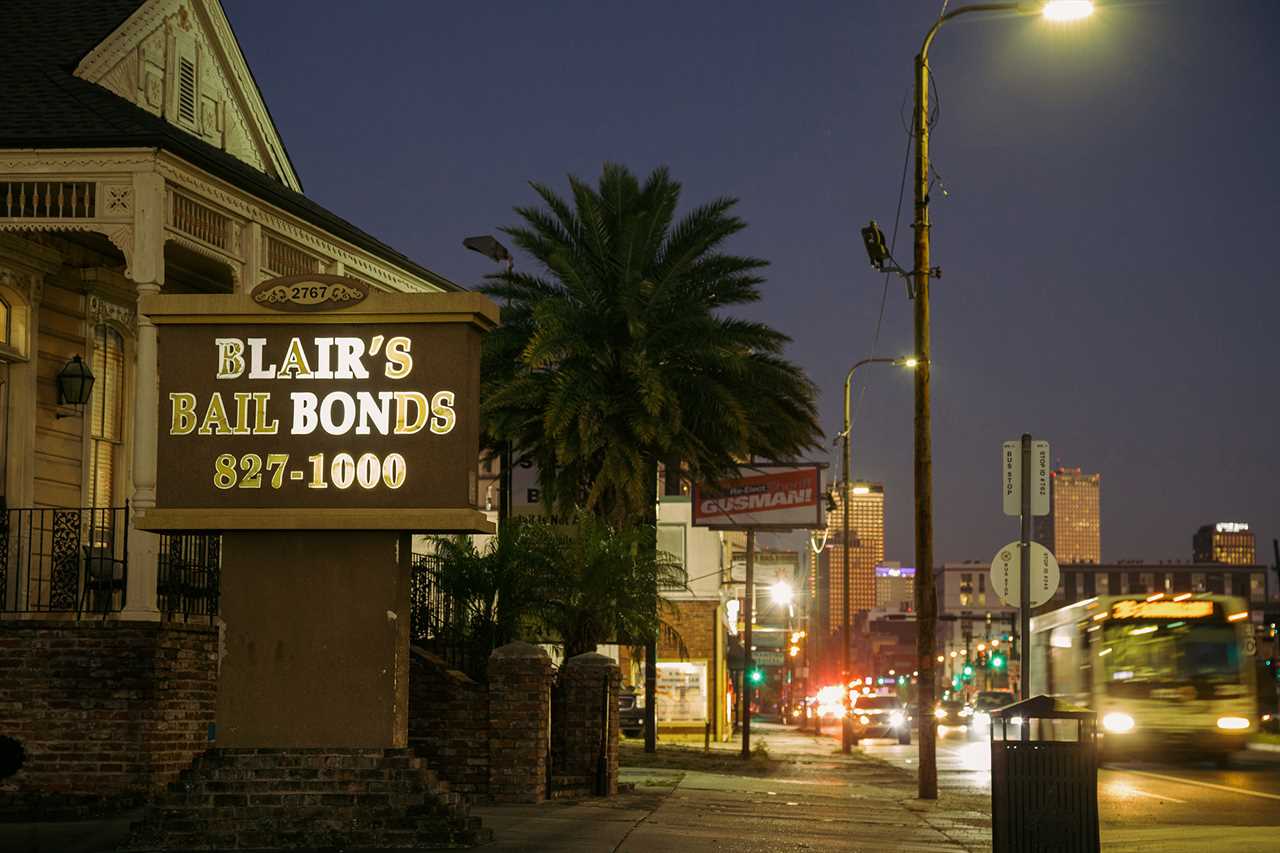

These deaths add to long-standing concerns about the safety of the approximately 900 people housed in the Orleans Justice Center (once called the Orleans Parish Prison), which falls under the control of New Orleans Sheriff Marlin Gusman. Gusman, who has held his seat since 2004, has long faced criticism from prison reform advocates, starting with his oversight of the facility during Hurricane Katrina. In 2008, the jail ranked among the deadliest in the nation. The next year, the Justice Department issued a report on what it said were unconstitutional and dangerous conditions inside the jail. In 2012, Gusman was sued, and the jail was placed under a consent decree, subjecting it to federal monitoring until it can bring confinement conditions up to legal standards.

Through it all, Gusman kept getting reelected, largely with support from New Orleans’ political establishment. Now, though, for the first time since 2014, he has a serious electoral challenger: progressive candidate Susan Hutson, who hopes to oust Gusman in the election this coming weekend with support from criminal justice reform groups around the city.

An attorney with a background in activism, Hutson served for more than a decade as the independent monitor for the New Orleans Police Department, which has been under its own consent decree since 2012. In that capacity, she pushed to reform a department long accused of misconduct in its policing, and the department saw modest improvements. As sheriff, Hutson wants to bring the jail into compliance with its consent decree and ultimately decrease the jail’s population. Taking a cue from the calls for reform that emerged after the death of George Floyd, she also hopes to work with local groups to push city leaders to invest more resources in the community and scale back the footprint of the police force.

The top two candidates after Saturday’s nonpartisan primary will advance to a December election if no one receives more than 50 percent of ballots cast; there are three other candidates in the race, but none are expected to garner a significant share of the votes, setting up a battle between Gusman and Hutson.

Beyond the stakes for New Orleans, the election represents one of the first big national tests of whether the criminal justice movement can make an impact on sheriff’s offices, which so far have remained largely impervious to reform, even as progressives and grassroots groups have had success in electing district attorneys and pushing modest local and state police reforms. Still, sheriffs present a uniquely challenging office to overhaul, particularly at a time when federal police reform efforts have failed, reform-minded prosecutors are facing recall elections and crime rates are ticking upward. The job of the sheriff has always had a strong tough-on-crime culture, and to date few progressive candidates have been willing to take on the challenge of reforming a system that touches everything from immigration to policing to jails. Because most sheriffs are elected at the county level, they also must appeal to a wide swath of voters, while left-leaning mayors in big cities can appoint their police chiefs and interview candidates from across the country.

Gusman argues he is the realist in the race — the only person who really understands how the Orleans Justice Center operates and can fulfill the requirements of, and ultimately end, the consent decree; he also wants to expand the jail so it can offer more mental health services. As for last year’s deaths, a representative for Gusman told me investigations into each had been completed and that staffing was not a factor. A campaign spokesperson added that Rettman was on a “detox protocol” for drugs and alcohol, but that he “reported no suicidal or self-harmful thoughts during his medical screenings.” The sheriff declined to make any further comment about death investigations at the Orleans Justice Center.

Gusman has deep ties to New Orleans’ Democratic establishment, having served as chief administrative officer for then-Mayor Marc Morial and on the city council for four years. Hutson also is a Democrat, like almost two-thirds of voters in New Orleans. Unlike almost every other sheriff candidate in the nation, though, she has never worked in law enforcement, which she believes positions her well in a city where activists have long called for racial justice in the criminal system. (Hutson is Black, as is Gusman.) “I’m not looking at it from [a cop’s] perspective at all,” she says. “I believe that this system — this system has got to be fundamentally changed.”

The election will be the first indication of whether that’s possible.

For the past decade, criminal justice reformers have taken to the ballot box to elect progressive-minded prosecutors and judges who vow to reduce penalties — or dismiss charges altogether — for low-level crimes, avoid excessive sentences and right the injustices of the past by reviewing questionable cases. More than two dozen progressive-minded prosecutors have managed to win elections in that time, including Kim Foxx in Cook County, Illinois (home to Chicago); Rachael Rollins in Boston; Larry Krasner in Philadelphia; and Chesa Boudin in San Francisco. Although these prosecutors have faced challenges once in office, their elections alone signaled a change.

Because sheriffs, like prosecutors, are elected officials, advocacy groups have been inspired to attempt a similar strategy to elect progressive sheriffs. But the results have been mixed at best, especially when it comes to reforming jails.

There have been recent successes, many related to immigration reforms. In 2016, after decades of organizing, Latino activists in Maricopa County, Arizona, ousted Joe Arpaio, the county’s fiercely anti-immigrant sheriff. (Liberal megadonor George Soros contributed $2 million to the effort, which probably helped.) In 2018, North Carolina voters elected a slate of reform-minded sheriffs in Mecklenburg, Durham and Wake counties, each of whom agreed to withdraw from a federal program that enables sheriffs to assist Immigration and Customs Enforcement in deporting jail inmates. And in 2020, Cobb County, Georgia, and Charleston County, South Carolina, both elected sheriffs who ran on reform platforms. Still, none of these candidates explicitly argued for downsizing their budgets or their jail populations — a core goal of many criminal justice reformers.

“I think there is a movement across the country of people who are fighting for something different,” says Max Rose, executive director of Sheriffs for Trusting Communities, a nonprofit that supports grassroots organizers in sheriff’s campaigns. “Elections are an important and limited tool in that fight.”

Almost all these new sheriffs are Black (Kristin Graziano, the new sheriff in Charleston County, is white and an out lesbian), which is significant because sheriffs have historically been predominately white and male, while the populations most affected by sheriffs’ work are disproportionately Black and Latino. A 2020 report by the Reflective Democracy Campaign found that 90 percent of the nation’s sheriffs are white men, while fewer than 3 percent are women.

There are signs that this pattern is changing. In Fort Bend County, Texas, a suburb of Houston, voters in 2020 elected the first Black sheriff since Reconstruction. In the recent sheriff’s election in Erie County, New York, Kimberly Beaty, a former deputy commissioner of the Buffalo Police Department, ran against Republican John Garcia. Beaty would be the first Black woman to hold that office; the election has come down to absentee ballots, which are still being counted. If elected, Hutson would be the first woman to serve as New Orleans sheriff, and the first Black woman.

Still, the barriers to electing progressive sheriffs remain high. Most sheriffs hold office for multiple terms, stretching to decades, often because of a mix of institutional entropy and a lack of public awareness about the office. Michael Zoorob, a postdoctoral researcher at Northeastern University, found in an analysis that sheriffs have an incumbency advantage that “far exceeds that of other local offices” such as city councilor, state representative or mayor. Much of this advantage, Zoorob wrote, comes from a sheriff’s nearly unchecked discretion, which can include the ability to hire and fire employees at will, award contracts, initiate investigations and block oversight. Plus, sheriff’s elections, as compared with other city races, tend to hinge on more suburban and rural voters who are more likely to lean conservative on criminal justice issues.

The sheriff’s race in New Orleans would be another milestone for criminal justice reform. Hutson sees herself as part of the broader movement to change the office of the sheriff; she says she is inspired by women like Graziano who have been elected on reform platforms, and she likes to talk about “Black girl magic.” But she also recognizes that, even if she wins, she will have a lot of work to do to overcome the history of abuses in the New Orleans jail.

Louisiana has a long history of high incarceration rates and heavy-handed sheriffs. In 19th century, the state’s sheriffs assisted in a practice known as convict leasing — the renting out of incarcerated people’s labor. Today, sheriffs can operate work-release programs, in which they keep the bulk of the incarcerated worker’s wages, and they can incarcerate people on behalf of state and federal agencies, for which they receive per diem pay from the government. The state also gives wide latitude to sheriffs to hire deputies and run their jails, including contracting with private health care providers. And the state sheriffs’ association holds significant political power, often lobbying to block criminal justice reforms. “Why would I want to be governor when I can be king?” one Louisiana sheriff once asked. (He is memorialized in a 14-foot statue in Metairie.)

New Orleans has long struggled with accountability in its justice system. In the 2012 suit against Gusman, a group of people housed in the Orleans Justice Center alleged horrific conditions: “Rapes, sexual assaults, and beatings are common place throughout the facility. Violence regularly occurs at the hands of sheriffs’ deputies, as well as other prisoners. The facility is full of homemade knives, or ‘shanks.’ People living with serious mental illnesses languish without treatment, left vulnerable to physical and sexual abuse,” the lawsuit read. Gusman challenged the lawsuit, and said the city wasn’t adequately funding the jail. After the federal government joined the suit, DOJ sought its consent decree, which was approved by a judge in 2013. In his ruling, the judge found that the conditions at the jail had become “an indelible stain on the community.” Since then, the jail has been under a federal monitor who oversees the jail’s mandated efforts to protect individuals from physical and sexual assault, provide adequate medical and mental health care, prevent suicides, and ensure adequate sanitation.

Gusman has bristled under the oversight. Last year, he argued in a motion to end the consent decree that he has done all he can to bring the jail up to snuff. And he has described the facility as “one of the most modern and functional” in the nation. But the federal monitors’ latest report, issued this past February after the deaths of Rettman, Freeman and Guild, castigated Gusman for inadequate medical care, excessive deputy turnover and persistent violence, in addition citing “extremely problematic” suicide prevention measures. The monitors also raised concerns that Gusman’s administration had not “adopt[ed] a culture where accountability is embraced as opposed to a culture where there is a reluctance to address the deficiencies and, in some instances, undermine the efforts of those whose job it is to provide information.”

Through a representative, Gusman said by email that most of the backsliding identified by the monitors was related to Covid-19 and a need for a new jail facility, and that the jail overall was heeding the monitor’s demands. “[W]e have full or substantial compliance on 167 of the 174 items in the monitor report. We are light years ahead of where we began,” the sheriff added.

Local journalism and watchdog groups have drawn attention to a host of other problems at the jail, and while many criminal justice reformers I spoke with supported Gusman in 2004, some have since soured on him. The latest battlefield is a proposed expansion of the New Orleans jail, called Phase III, which would add at least 89 new beds for mental health services, at a cost of $50 million. (Previous phases included the post-Katrina construction of the current Orleans Justice Center facility, which opened in 2015.) The city of New Orleans, including the mayor and the district attorney, oppose Phase III construction, as do community groups. Hutson has joined them, arguing that the current jail building can be retrofitted for mental health needs. She says she would rather see more mental health resources in the community (which a sheriff can support politically but not actually control). Gusman supports the new construction, as do the federal monitors. “I need the appropriate facility to be able to safely provide these individuals with treatment to stabilize and hopefully improve their conditions prior to the courts ordering their return to the community,” Gusman told me by email.

Norris Henderson, founder and executive director of VOTE, a grassroots organization run by formerly incarcerated people advocating for criminal justice reform, has worked with Gusman before. But he told me bluntly: “When you can’t protect people inside of a jail, when you can’t provide the quality of care inside of the jail, it’s time to move on.”

In her campaign, Hutson is drawing on her activist background to highlight how she would approach the job differently. Before she was born, her grandfather was shot and killed by a sheriff’s deputy in East Texas, an incident she says inspired her to fight racism in the criminal justice system. As a college student at the University of Pennsylvania, she protested South African apartheid and agitated for change after the 1985 MOVE bombing, when the Philadelphia police bombed a Black neighborhood, killing 11 people. After law school, she worked as a prosecutor and police overseer in Austin, Texas, and Los Angeles before landing in New Orleans.

As the independent police monitor, a position created by the city to oversee the police department, Hutson made advisory opinions, including reviewing use-of-force incidents, complaints and disciplinary procedures, as well as helping the department improve community relations. But she did not have the ability to implement reform herself. “You use your bully pulpit, but you’re not the actual decision-maker,” she explains. Still, serious use-of-force incidents in the New Orleans police went from 13 in 2013 to one in 2018, and, in polls, residents have cited more positive attitudes toward the police. (The New Orleans Police Department declined to comment on Hutson or “any candidates for public office.”) Before she stepped down to run for sheriff, Huston was president of the National Association for Citizen Oversight of Law Enforcement and was cited around the country for her expertise on police oversight.

Ahead of the election, Hutson has been campaigning around the city, trying to make sure voters know her name and talking up her commitment to what she calls the “three c’s” of correction: care, custody and control. Her platform is ambitious. She wants to end the jail’s contract with Wellpath, the private company that provides health care to people inside the Justice Center, replacing it with health professionals the sheriff’s office can hire and control. She also wants to avoid increasing the jail population; encourage people inside the jail to vote and engage in rehabilitative programs; and, in her words, “comply with the consent decree and implement strict financial controls” over the jail’s budget and expenditures.

Most important, she says, is to “listen to what our community is saying.” For Hutson, that means taking seriously grassroots demands for decarceration and working with the city to try to shift funding to community care, which is not something a sheriff would typically do. “I want to be a part of changing the system to be closer to the point where we may not need [jails] anymore,” she says. “Is it going to happen in my lifetime? I don't know. But I definitely want to do my part.”

Gusman has argued that he has his own progressive credentials, pointing to a high school for teens that he opened at the jail, and saying he could do more with additional funding from the city. “I have to deal with a divergence between politics and reality about our jail,” he wrote by email. In the campaign, he has the backing of the AFL-CIO, the Democratic Party and the Democratic governor, John Bel Edwards. “I am confident he’ll continue to lead the city to brighter days ahead once he’s re-elected,” the governor said of Gusman in a statement. Gusman’s political connections have helped him raise $244,000 so far. Hutson has gotten support from a number of progressive groups but has raised closer to $55,000, according to the most recent filings.

Louisiana’s history suggests Gusman might have the upper hand in the race. In 2019, a progressive candidate sought to oust the sheriff in East Baton Rouge — whose jail has the highest number of in-custody deaths of any parish in Louisiana — but the effort failed. New Orleans has been more open to reform in recent years, though. Last December, voters elected City Councilmember Jason Williams, who ran on a reform platform, as district attorney, along with new two new judges who have welcomed oversight and released people who were wrongfully incarcerated. Although Williams has disappointed some supporters, Hutson’s backers are counting on that same energy to rally activists and grassroots organizations to help propel her into office.

Still, even some of her supporters admit to having questions about how much a progressive sheriff can actually change the system if elected. In Los Angeles, Democratic voters elected Alex Villanueva as sheriff in 2018 based on his promises of reform, but he has found himself fighting with the Civilian Oversight Commission that monitors the sheriff’s department, the county Board of Supervisors, the D.A. and pretty much everyone else who stands in his way. In Mecklenburg County, Sheriff Garry McFadden, elected in 2018 on a reform platform, has had to answer to a slate of jail deaths and protests.

Those who work on progressive sheriff campaigns are not naïve to the challenges. “I do not believe a single candidate can be our salvation,” says Sade Dumas, executive director of the Orleans Parish Prison Reform Coalition, one of the groups that opposes the New Orleans jail expansion. “But I believe a progressive sheriff can make things less bad by refusing to enact regressive, harmful practices.”

Hutson’s supporters are hopeful that, if elected, she has the best chance of overhauling the Orleans Justice Center and saving the lives of people like Christian Freeman, the man who had drugs in his system when he collapsed in the jail. Freeman had been incarcerated for a nonviolent crime and had not yet been convicted. His uncle Shannon Freeman told the Advocate that when his nephew, who struggled with drugs, was arrested, the family initially was relieved, hoping Christian would finally be safe. But after the death, Shannon, who calls himself as a conservative on criminal justice issues, shared another view: going to jail “shouldn’t be a death sentence.”

----------------------------------------

By: Jessica Pishko

Title: She Wants to Fix One of Louisiana’s Deadliest Jails. She Needs to Beat the Sheriff First.

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/11/10/new-orleans-sheriff-election-progressive-reformer-tough-crime-incumbent-519654

Published Date: Wed, 10 Nov 2021 04:30:08 EST

Did you miss our previous article...

https://consumernewsnetwork.com/politics-us/bidens-economy-is-being-stricken-by-soaring-inflation