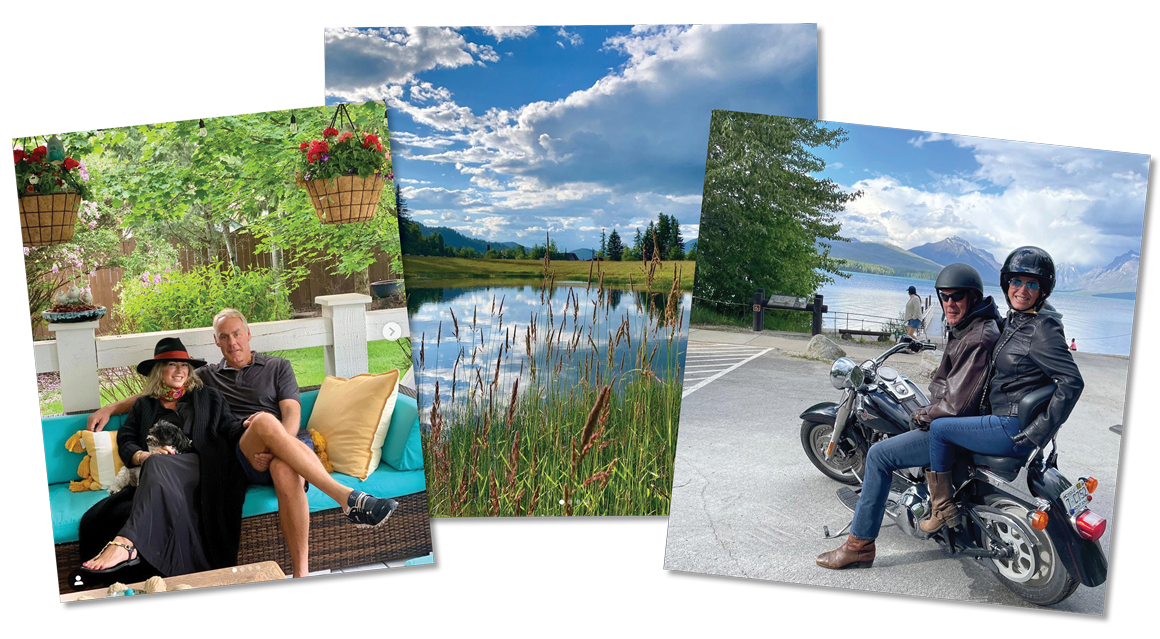

WHITEFISH, Mont. — Ryan Zinke likes to tout his fifth-generation Montana roots. On his first day as Donald Trump’s Interior secretary, in 2017, the tall, boot-clad ex-Navy Seal famously galloped to work on horseback in blue jeans and a black cowboy hat. This past June, when Zinke kicked off a new congressional campaign, he cruised on the back of a Harley Davidson through some of the state’s most picturesque backdrops, from Glacier National Park to Billings, Montana’s largest city. His wife, Lolita, documented the tour on Instagram with the hashtag #Montanalife.

“I grew up in Montana, where if someone’s barn is on fire, you don’t ask whether he’s Republican or Democrat,” Zinke told a local TV station after filing his campaign paperwork in April. “What I care about is: Do you love your country, and do we want to improve our conditions for others around us in Montana?”

Zinke, 59, right now appears to be the leading candidate to represent Montana’s newly designated 2nd congressional district. He has Trump’s endorsement and strong name recognition. But his opponents have seized on a weak point for a politician running as a son of Montana.

“We really haven’t seen him in Montana,” said Cora Neumann, a Democrat from Bozeman who is one of four candidates running against Zinke so far.

As a candidate, Zinke already has his share of questions to answer: It’s been almost three years since he resigned from the Interior Department amid a series of ethics scandals and federal investigations, some of which were referred to the Department of Justice. But in Montana, perhaps the most acute question now is about exactly where he lives.

It’s long been known that Zinke splits his time between Whitefish and Santa Barbara, California, where his wife owns property and a yacht — a point critics have seized on in his previous congressional races, in 2014 and 2016. And over the past several months, Zinke has conspicuously traveled across Montana, frequently posting photos on his new Instagram account, @zinkeformontana. But when I visited the state over the summer, a half-dozen residents of Whitefish and the closest city, Kalispell, told me that, until Zinke launched his most recent campaign, they hadn’t seen him around much since he left Washington in late 2018. The most recently available FEC data shows Zinke has received campaign donations — about $181,000, as of July — largely from non-Montanans, as well.

Zinke’s political opponents are clearly trying to emphasize the point — “I think it’s pretty obvious when you show up in March with a really killer tan that you haven’t been here for a long time,” said Jennifer Fielder, a Republican former state senator who supports Zinke’s GOP primary challenger — and his wife’s social media has only added fuel to their critique. From late 2018 until spring of this year, when Zinke’s campaign launched, Lolita Zinke’s Instagram feed has featured considerably more photos of her and her husband in Santa Barbara than in Montana. Perhaps more telling is when the photos were posted: Her account documents the Zinkes spending holidays in Santa Barbara and quarantining there during the early days of the pandemic. They appear in Montana mostly during the summer months.

“I don’t think Ryan has been a true Montanan for a very long time,” said Fielder, now a member of the Montana Public Service Commission, a state regulatory agency.

When I contacted Zinke’s campaign to ask about his residence, I was told he still lives in his hometown of Whitefish, at the address given on his April FEC campaign filing. In July, I flew to Montana and drove to that address, a handsome, two-story, chalet-style home within walking distance of downtown. In 2013, Zinke petitioned the city of Whitefish to let him convert the home he and his wife had built into a bed-and-breakfast; that didn’t happen, but a sign outside still advertises the building as The Snowfrog Inn.

On a 98-degree day over the summer, there were several cars and trucks parked in the driveway of the building. Exiting the property, Nikita Packard identified herself as Zinke’s son’s 22-year-old girlfriend and told a POLITICO photographer that she lived in the house, but that Zinke did not. Packard did not say where the former secretary resides permanently, and she did not respond to later attempts to confirm details. A former tenant of Zinke’s, who until 2019 lived at a rental property of his next door and who asked not to be named for privacy reasons, described interacting with the Zinkes but said they did not appear to live in the Snowfrog building full-time.

In addition to the Snowfrog Inn, property and business records show that Zinke owns at least three other parcels in Whitefish through LLCs. According to information Zinke disclosed during his first congressional race, at least two Whitefish properties have been used as rentals; another property is open land. Public records also list a lakeside property in nearby Marion, Montana, in Ryan Zinke’s name, but Zinke’s campaign did not cite the plot as his residence and did not respond when asked about the address.

Speaking on behalf of the campaign, a consultant said the idea that Zinke does not live in Montana is “absurd.” “It’s flat out wrong. All the Pinocchios,” Heather Swift wrote through a Twitter direct message. “He travelled a lot for work and pleasure but he still lived in Montana. It’s not a hard concept.” Swift said Zinke’s permanent residence for years has been the site of the Snowfrog Inn. The former Zinke tenant told me the Snowfrog had been used as a multiunit rental property, and two other Montana sources said they had heard the same. But in comments to POLITICO, the Zinke campaign said one portion of the property had been rented only “briefly” when Zinke was at Interior and that Packard “does not and never has lived at the Zinkes’ home” and was likely visiting Zinke’s son. The campaign did not respond when asked whether Zinke lives at the Snowfrog full-time.

“Obviously, he travels for some of his business endeavors, as we all do,” said Don “K” Kaltschmidt, a Kalispell resident who chairs the Montana Republican Party and is a friend of the Zinkes. “He’s a Montana resident. … It’s not unusual for Montanans to have, you know, residences outside of the state.”

Already, Zinke’s candidacy rests on the hope that Montana voters are willing to overlook some controversy. Although he denies any wrongdoing at Interior, the DOJ has not officially completed its work. And there is a chance Zinke still could benefit from the business deal at the center of one investigation: A sale is pending on the plot of land around which the deal was focused, and a planned development could raise Zinke’s property values in the vicinity.

As Zinke wades back into national politics and tries to get back to Washington, the question is how much — or whether — his scandals will matter in the congressional race. The state’s political leanings are working in Zinke’s favor. Republicans swept every statewide race last year, and Trump won by 16 percentage points. That was a smaller margin of victory than in 2016, though. Montana also is a state with a strong independent streak, a sense of pride and a growing skepticism toward the outsiders who have flocked here in recent years, or who only parachute in for the summer months — a category some locals say includes Ryan Zinke.

“That thing of getting on the horse and riding into the Interior Department — give me a break. What is this, Gene Autry and Roy Rogers, for God’s sake?” said Carol Williams, the former state Democratic majority leader who served with Zinke in the legislature. “Montanans don’t do that.”

When I visited Whitefish in July, the towering Mission Mountains, famous for surrounding the Flathead Valley with their snowy peaks and as the gateway to Glacier National Park, were invisible through the screen of brown, ashy air blown in from the wildfires raging in Idaho and Oregon. It’s the type of weather Zinke seized on as Interior secretary to explain how the lack of logging in mismanaged national forests fuels fires.

But Zinke wasn’t in town. His campaign consultant had not responded to requests to make him available for an interview in his home state. I eventually learned from his wife’s Instagram account that the Zinkes were on a beach vacation in Bodrum, Turkey. (Lolita has family ties to Turkey, and the Zinkes travel there often, including at least three separate trips documented on Lolita’s Instagram account in 2019.)

Zinke grew up a Montanan and is well-known in his hometown of Whitefish, where his father was a plumber. He was voted senior class president and most likely to succeed at Whitefish High School, and played quarterback on the football team, ultimately getting recruited by the University of Oregon. After he served as a Navy Seal commander, he returned to Montana. According to Zinke’s campaign, he built the Snowfrog on land that had belonged to his grandmother and that Zinke purchased from his mother. Zinke served two terms in the state Senate before he was elected to Congress, where he held office from 2015 to 2017. After two years in that job, he became the first Montanan ever to serve in a presidential Cabinet.

When Zinke left Washington in 2018, he went to work for a Nevada-based gold mining company and later became the first of Trump’s Cabinet secretaries to join a lobbying firm, though the enterprise was short-lived. Since then, several locals I spoke with said he has not been a noticeable presence in Whitefish.

Lolita Zinke’s photos on Instagram show that in recent years she and her family have bought Christmas trees, celebrated Easter, worked on backyard renovations and gone horseback riding in and around the beachside enclave of Santa Barbara, which is two hours north of Los Angeles and home to celebrities including Ellen DeGeneres and Meghan Markle. The Zinkes also appear to have quarantined together in Santa Barbara, with Lolita posting a photo of a shirtless Zinke on Memorial Day 2020, alongside a caption referring to him as “my quarenteammate” and the hashtags #godblessamerica #workoutmotivation and, puzzlingly, #bengazi. (The Instagram account is private, but Lolita accepted my request to follow her from an account where I identify myself as a journalist.)

Lolita was born and raised in Santa Barbara. Property records show she owns two parcels on more than 10 acres in a community locals call The Mesa because of the table-like formation the hill makes as it juts out over the Pacific Ocean. The land has been in Zinke’s wife’s family for decades, according to records, and sits on a street named Las Manos, an apparent reference to her maiden name, Hand. The family’s main house is perched atop a bluff with panoramic views of the white walls and terracotta roofs that dot the landscape in a city sometimes referred to as the “American Riviera.”

Documents provided by the City of Santa Barbara show Lolita also owns a 41-foot yacht that’s docked in the Santa Barbara harbor — a boat named Freyja’s Dance, after the Norse goddess. According to Lolita’s frequent Instagram posts, she is a member of the local yacht club, which looks up at the towering Santa Ynez Mountains.

Other sources have placed Zinke in Santa Barbara, as well. In 2019, months after Zinke had resigned from the Interior Department, the Zinkes hosted former Turkish Prime Minister Binali Yildirim for brunch at their home in Santa Barbara, before Yildirim traveled to New York to attend the annual United Nations General Assembly, according to the Montecito Journal. Shortly before his official campaign launch this summer, Zinke also spoke to a group at a rooftop venue in Santa Barbara overlooking the Pacific Ocean, where he referred to D.C. as a “cesspool,” according to an Instagram post from David Spady, a California-based conservative media consultant who served as an adviser to Zinke in Washington.

Zinke’s campaign did not answer questions about the amount of time the candidate has spent in California compared with Montana. Legally, congressional candidates only need to be inhabitants of the state where they’re running at the time of the election. And some Montanans I spoke to for this story shrugged their shoulders at the time Zinke has spent out of state. One former Republican elected official called the residency questions “a canard.” “He still has a family home. After he was hounded out of the administration, he had significant legal bills to pay, so he had to do some work to get that covered,” said the former official, who asked to remain anonymous to speak openly.

“They’ve been saying that about Zinke since he first ran for office here, and that didn’t stick then,” added Chris Shipp, former executive director of the Montana GOP and Trump’s state director in 2016. “Just because someone has family in another state that they go and spend time with does not negate the fact that they are a Montanan.”

For Zinke’s opponents, the residency matter is fuel for their argument that he cares more about his own interests than Montanans’. They hope to stoke a growing cultural tension: There’s a sharp distinction here between the hardened locals who can withstand the winters and the summer part-timers, many of them from the West Coast, who have bought up homes here and helped drive Montana toward the worst housing crisis in its history. Locals have taken to calling Bozeman, where the price of homes is up 25 percent from the previous year, “Boz Angeles.”

But there’s more than cultural animus to the argument that Zinke has become, effectively, an outsider to his own state. Based on his most recent fundraising totals, nearly half of his campaign donations have come from donors in Texas. His largest single donation came from an oil company CEO in Dallas.

“Maybe if he had come back after he resigned as Interior secretary and moved back to Whitefish and came back to the community, that would be something. But Ryan didn’t show up until there was an announcement for an open seat,” said Al Olszewski, a former Montana state senator who is Zinke’s sole declared Republican challenger.

As he runs for Congress, Zinke is well aware of the Trump-era scandals that trail him, and he has painted a picture of himself as a man who was maligned from the get-go, by both the agency he ran and the media who covered him.

“When you’re a department … you have people who are protesting you, complaining. I went through 18 investigations from my socks to doors, because these people wanted to stop us from day one,” Zinke said in an Aug. 26 interview on a conservative podcast. “This is what these information oligarchs and the media has become. … We’ve seen manipulation, we’ve seen dishonesty, we’ve seen bias. The Department of Justice, the IGs themselves became weaponized.”

All told, Zinke faced nearly 20 federal probes. Zinke asserted on the podcast that he had done no wrong. “All of them ran their course,” he said of the investigations. “No wrongdoing in the end, and there was no wrongdoing at the beginning.” The Zinke campaign told POLITICO in a statement that “every investigation ran its course and came out with no violations of ethics laws or rules.”

In fact, the Interior Department inspector general and the U.S. Office of Special Counsel did fault Zinke for ethics violations; evidence related to one ethics probe was presented to a grand jury. Nor has every inquiry officially closed: At least two DOJ investigations are on pause, according to a former official in the Interior Department’s inspector general’s office and a congressional source who was involved in the issue early on. The former official in the IG’s office said the Interior inspector general is waiting to release his own report once the DOJ’s work is completed. The IG’s office declined to comment. The DOJ did not respond to a request for comment on the status of the investigations.

“You really can’t pressure DOJ,” said the former official in the IG’s office, who was not authorized to speak publicly. “The hairs go up on their back no matter who you are or who they are.”

One of the investigations examines whether Zinke violated federal conflict of interest rules by engaging in business negotiations with the owner of a large property being developed just across the street from the Snowfrog Inn in Whitefish, at 95 Karrow Ave. It’s an ongoing project Zinke could still benefit from, even as he launches his run for Congress.

In the project’s early stages, POLITICO reported, Zinke’s wife agreed to let the developers use parts of an adjacent property she operates as a nonprofit park honoring veterans in order to build a parking lot for future businesses at 95 Karrow. The project’s proposal included plans for a microbrewery — a business idea Ryan Zinke had proposed years earlier and spent years pushing the city of Whitefish to allow. Congressional investigators later found through an email that Zinke had hosted developers for the project — including David Lesar, chairman of oil services giant Halliburton, whose energy interests Zinke regulated as Interior Secretary, and Casey Malmquist, the developer of 95 Karrow — at his office in Washington. POLITICO reported at the time that the men had discussed the real estate project over dinner that night.

Now, the developers appear to be selling the 14 acres at 95 Karrow Ave., and are touting the potential brewery and the parking lot as features of the property. In January, the site was listed for $10 million. The land remains undeveloped — a plot of overgrown weeds, potholes and gravel. But the listing advertises the space as a “developer’s dream,” and incorporates recently approved plans for a multiuse development, including a 4,240 sq. ft. microbrewery and the use of 137 parking spots on the adjacent Great Northern Veterans Peace Park. Online records show a sale of 95 Karrow is currently pending.

It’s not clear who the buyer is or who will manage the brewery, if constructed, but the development could raise the value of neighboring properties the Zinkes own. And while the nonprofit that has offered its space for parking is led by Lolita — Zinke stepped down from running it prior to becoming Interior Secretary — he appears to continue to support its efforts: He donated $11,594 in leftover campaign funds to the nonprofit in December 2020, according to FEC filings.

Malmquist, the developer, told me the Zinkes are not involved in the brewery or financially tied to the broader development. He described the project’s use of the veterans park as a “shared parking agreement” that was established in late 2017 and said the developers would cover the costs of converting the land into parking. He said he has only interacted with Lolita over the parking issue. Asked about the meeting he had with Zinke in his Interior Department office and a subsequent private tour Zinke gave him and Lesar of the Lincoln Memorial, Malmquist characterized the interactions as a D.C. welcome for fellow Montanans and said he had not discussed the 95 Karrow development with Zinke on the trip.

The Zinke campaign did not respond to questions about the deal. Lesar could not be reached for comment. The real estate agent for 95 Karrow did not respond to requests for comment.

Some Montanans I spoke with argue Zinke has become part of Washington’s great revolving door, more invested in getting back to D.C. and back to the relationships it has offered him than he is in serving the state. But Zinke’s supporters say his business dealings and history in Washington won’t detract from his campaign. “I think the general impression was that Trump was hounded from day one, and everybody appointed was hounded from day one, so I don’t think it will have any impact to Zinke’s race,” said the former Republican Montana elected official who asked not to be named. “None of those charges stuck, to my knowledge.”

“If you didn’t know anything about Montana and Montana voters, all you need to do is remember that Greg Gianforte” — then a House candidate, now governor — “body-slammed a reporter a few days before his [congressional] election and probably picked up 5 points,” added Sen. Kevin Cramer (R-N.D.), the first member of Congress to endorse Zinke in the current campaign. “So, there’s that Western independent cowboy spirit.”

A sense of uncertainty surrounds the race for Montana’s 2nd district for reasons beyond Zinke’s residency or business dealings. For one thing, the district’s lines won’t officially be drawn until early next year — and there’s a possibility Zinke could end up in the uncomfortable position of running against Montana’s current congressman, Republican Matt Rosendale, who lives in the eastern part of the state.

The GOP favors keeping the East-West divide that existed the last time Montana had two House representatives, in the 1990s, which Republicans say better reflects local identity. That configuration would likely give Montana two GOP victories, and in turn could give national Republicans another seat in the House. But Democrats in Montana are pushing to carve out Flathead County, home to Whitefish and the deep-red city of Kalispell, to make it part of the Eastern district. That would push Zinke into Rosendale’s district and give the Democratic candidates — Cora Neumann, state Rep. Laurie Bishop and lawyer Monica Tranel — a better shot at winning the Western district.

Bob Brown, a Whitefish-based former Republican president of the Montana Senate who helped Zinke get his start in state politics, says Zinke is a “pretty strong frontrunner” for the new 2nd district if it includes Flathead County. But, Brown pointed out, “Zinke barely beat Rosendale in his first congressional primary.” Swift, Zinke’s campaign consultant, said Zinke plans to run in the district where he lives and doesn’t plan to primary Rosendale.

There is not good polling yet for the race, but Zinke is facing competition on both the left and the right. His Democratic opponents are hoping the state can embrace its more purple past. Montana had a Democratic governor until recently and still has one Democratic U.S. senator, plus it has one of the highest rates of ticket-splitting of any state. Neumann recently reported raising $469,000 in the third quarter of the year; Tranel reported $244,000; and Bishop reported $117,000.

Of course, Republicans’ widespread success in the state last year gives Zinke a major advantage. But he also faces a primary opponent who has sought to tar him as too moderate and is trying to rally Montana’s militia-friendly, gun-rights community against him. Over the past year, a housing shortage, gun control and masks ignited cultural clashes across the state. Without Democratic veto power in the governor’s seat for the first time in 16 years, the Republican-majority legislature enacted a flurry of laws.

Olszewski, Zinke’s Republican challenger, is trying to seize on that momentum. Known locally as Dr. Al, the former orthopedic surgeon and Air Force veteran served in the state legislature for six years. He has long championed anti-abortion legislation and is well-liked among grassroots voters in Kalispell, where he lives. Olszewski’s campaign spokesperson said the candidate is not yet releasing his third-quarter fundraising totals but that, “the campaign reached its quarterly goal and is proud of the strong support from Montanans and not out-of-state special interests.” Zinke’s campaign did not respond when asked about its own third-quarter totals.

His Trump endorsement notwithstanding, Zinke has a relatively moderate history in Montana, a point Olszewski emphasizes as a knock against him. When he started in politics as a state senator, Zinke voted in favor of gun control and was a strong land conservation supporter. Carol Williams, the former Democratic majority leader, said she bestowed on Zinke the honorary title of “most likely to vote with Democrats.” “I liked him. We had a great relationship. He voted with Democrats a lot, he really did,” Williams told me in Missoula.

Yet, Olszewski has his own controversies. He officially announced his campaign at the headquarters of the Flathead Liberty Coalition, an organization that recently has advocated against mask and vaccine mandates and in favor of Second Amendment rights, and last year he was photographed with reported members of the Yellowstone Militia, an armed anti-government group, while protesting Covid-19 stay-at-home orders. (Flathead County has a history of anti-government, far-right organizing.)

Whatever the race holds for Ryan Zinke, the election could solidify how Montanans see their identity going forward — as a purple or a deeper red state, as a community of 1 million locals or increasingly a destination for outsiders. Pat Williams, a Democrat who represented the state’s Western congressional district until it was eliminated in 1993 (and who is married to Carol Williams), recalls a time when Republicans would gladly vote for him. But politics here has shifted, to Zinke’s likely advantage. “That’s not happened in my lifetime,” Williams said of last year’s Republican sweep in Montana. “I didn’t see it coming. I don’t think Republicans saw it coming, frankly.”

Members of both parties told me they hope whoever is their new representative stays in the seat for the long haul, allowing one of Montana’s few representatives in Washington to gain the additional power that comes with seniority in Congress; Zinke got pushback from locals when he resigned from the House after one term to serve in Trump’s Cabinet. Pat Williams views that with concern: “How long will he be congressman before he moves around again?”

----------------------------------------

By: Miranda Green

Title: Ryan Zinke Wants to Be Montana’s Next Congressman. So Why Is He Spending So Much Time in California?

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/10/08/ryan-zinke-congress-montana-santa-barbara-2022-514780

Published Date: Fri, 08 Oct 2021 03:30:45 EST