Practically any sign of authority made P.J. O’Rourke grit his teeth — or, if one were in reach of his foot, stomp on a gas pedal. I learned this the hard way when we were driving around Panama City in 1987, as demonstrations against Manuel Noriega — the military dictator Panamanians referred to unaffectionately as Pineapple Face — were growing in size and intensity. We were, as the journalistic lingo of Central America at the time had it, looking for some bang-bang, and P.J., who was at the wheel of the car, was getting impatient at our lack of success.

So when a uniformed Panamanian cop standing at an intersection raised a hand-held stop sign, P.J. snorted in gringo contempt. “What’s he gonna do, chase me on foot?” he hooted as we blew by the angry policeman. My reply — “Ummm, P.J….”, which would be repeated many times over the next 20 minutes or so — was interrupted by the blare of a siren from a motorcycle-mounted cop, who was radioing for reinforcements. We were soon followed by three of them as P.J., channeling his not-so-inner Bullitt, went careening around city streets at 60 mph.

Noriega’s baton-swinging gendarmes were none too friendly toward American journalists under the best of circumstances, which these were definitely not, and when P.J. finally pulled over in a residential cul-de-sac, I seriously thought they were going to beat him (or, worse, both of us) into a gringo pancake. P.J. spoke no Spanish, so it was up to me to jump out of the car and start chattering a defense as the cops approached. P.J. later told me that he supposed — with considerable accuracy — I was telling them “what an arrogant cake-eating pecker-wit of a prostitute-mothered norteamericano earthworm” he was. The cops, with a keen professional regard for filthy invective, were impressed, and we headed (slowly) back to the hotel for a drink, or several.

I recall this story not just because it amused any number of reporters slouched around bars in Tegucigalpa and Managua, but because it reveals some important things about P.J., the slash-and-burn libertarian satirist who died of cancer this week at the age of 74. One is that his written mania for fast and potentially lethal automobiles was barely, if at all, exaggerated. (Of car accidents, he once wrote disdainfully: “They don’t hurt nearly as much as you’d think. That’s because you’re in shock and can’t feel pain, or if you aren’t in shock, you’re dead, and that doesn’t hurt at all so far as we know.”)

The other was his utter rage at seeing people pushed around: not only by cops but border guards, zoning boards, liquor-licensing commissions, soldiers, Trotskyite pickets, product-safety engineers, Keynesian economists, Unitarian theologians and anybody else who thought they were entitled to tell you what to do. O’Rourke offered his observations about everything from 18th-century mercantilism to the etiquette of food fights, but the foundation of all his work was: Mind your own business and leave me alone. “There is only one basic human right, the right to do as you damn well please,” P.J. wrote. “And with it comes the only basic human duty, the duty to take the consequences.”

Though we hadn’t seen one another lately, I had been a friend of P.J.’s for 40 years or so. As editor of a little-known and even less-remembered libertarian magazine called Inquiry, I gave him his first assignment in political journalism, and he wrote the foreword to my book about Nicaragua. And actually, I had been following his career long before that, since he joined the staff of the National Lampoon — the holy scripture of 1970s college kids — in 1973.

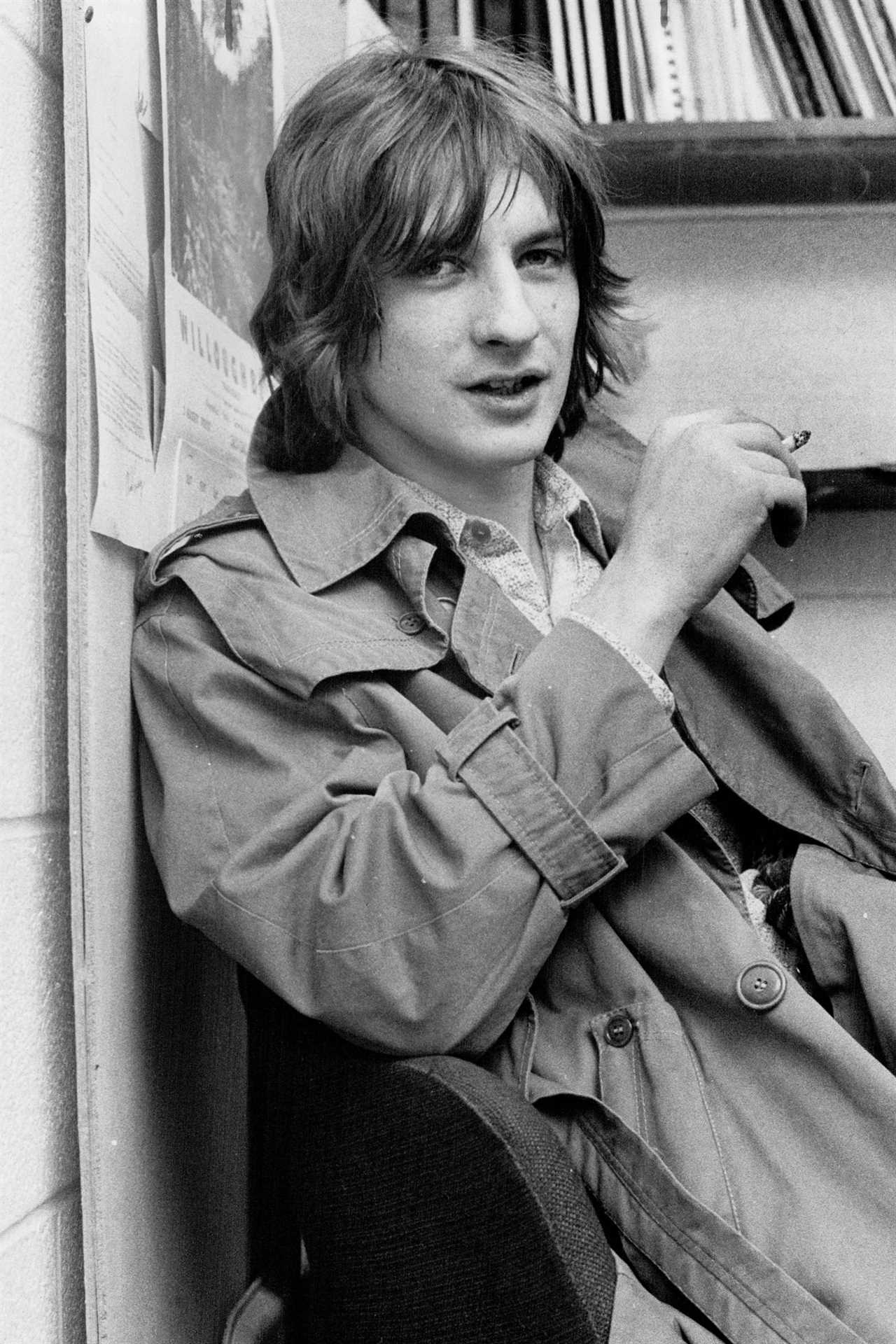

He arrived at the Lampoon as a 26-year-old Maoist whose work experience consisted mostly of writing for underground papers with names like The Rip Off Review of Western Culture after fleeing from a desolate Ohio childhood. (How desolate? On his first date, he took a girl to see West Side Story. “We didn’t know anything about it, and we were pretty surprised to see Puerto Rican gang-bangers dancing around New York slums on their toes,” he told me. “I didn’t get a goodnight kiss. Or a second date.”) He started out as a gofer but moved steadily up the editorial hierarchy as a hard-working guy who despite his tendency to lapse into Marxist babble, liked to write pieces about fast cars and faster girls. The first Lampoon issue he edited was titled “Pubescence,” with a teenage girl on the cover holding out a maraschino cherry, metaphorically, I’m sure.

The Lampoon, however, was already subtly at work undermining P.J.’s adoration for Chairman Mao. Part of his rapid rise at the magazine was that he was one of the few guys on the staff (yes, they were nearly all men) who understood that it had to make money to stay afloat; smoking dope all night and then stumbling in at 3 p.m. wasn’t a viable editorial strategy. At the same time, his nascent libertarianism — in its most primitive form, resistance to bullying — was bubbling to the surface as he dealt all day long with a mostly Harvard-educated staff that had no intention of taking orders from a guy who graduated from something called Miami of Ohio.

Their war, at first a quiet sitzkrieg, bust into the open in 1975 when P.J., in a published “letter from the editor,” ridiculed “a certain fancy-pants educational institution” as a place where students “spent four years clasping their books to their chests with both hands, drinking Pink Ladies and learning how to ride sidesaddle.” The staff retaliated with humiliating pranks like maintaining a stony and total silence when a PBS camera crew came to film an editorial meeting. P.J.’s favorite editorial instruction became, “Go eat a bowl of suck.”

By 1975, P.J. had cut his hair short; by 1976, he was voting for Gerald Ford; by 1980, he was resigning as editor in chief despite a wildly successful tenure that included publishing the stories that eventually morphed into the National Lampoon Vacation movies, as well as the withering Sunday Newspaper Parody of a stultifying midwestern journal called the Dacron, Ohio Republican-Democrat. (Banner headline: TWO DACRON WOMEN FEARED MISSING IN VOLCANIC DISASTER. Subhead: Japan Destroyed.)

He spent a few years freelancing, mostly for magazines like Car & Driver where drinking and driving was regarded as a comic staple rather than a threat to America’s children. When I saw an interview with him in Penthouse in 1982 where he meandered into a brief tirade against seat belts and other conspiracies by what he called Safety Nazis, I wondered if he’d be interested in turning his rant into a piece for Inquiry. He was: “I’ve been thinking I might like to do some political stuff.” His first piece had exactly the frenzied mad-dog libertarian texture we wanted: “Allen Ginsberg said he saw the best minds of his generation destroyed by madness. I have seen the best minds of my generation destroy a half gross of Tylenol with a ball peen hammer.” He was soon getting assignments from Playboy and Rolling Stone, and political stuff it was the rest of the way.

I don’t know if P.J. regarded himself as a libertarian when we had that first story chat. I don’t recall either of us using the word, which wasn’t yet much of a political trope. And, for a long time, his writing was not explicitly ideological. He went to hellish little war-torn and famine-ravaged developing countries, reported their depravity, talked about what went wrong (I often wondered if Rolling Stone readers noticed how frequently the problem started with collectivist economics) and got the hell out.

But as time went by, his work grew more complex and his analysis more abstract. From writing of Central Asia that “the main thing to be learned about foreign policy in this part of the world is that a wise foreign policy would be one that kept you out of here” he moved to writing a book-length study of Adam Smith’s The Wealth Of Nations and a comprehensive takeout on American politics.

He was, I think, the first member of the Baby Boomer chattering class to turn on his own generation, for its vacuity (“The 1960s was an era of big thoughts. And yet, amazingly, each of these thoughts could fit on a T-shirt.”) and its preening self-regard (“We are the generation that changed everything. Of all the eras and epochs of Americans, ours is the one that made the biggest impression — on ourselves.”).

There was literally nothing he couldn’t, or wouldn’t, lacerate. Democracy: “Imagine if all of life were determined by majority rule. Every meal would be a pizza. Every pair of pants, even those in a Brooks Brothers suit, would be stone-washed denim. Celebrity diet and exercise books would be the only thing on the shelves at the library.” The Washington press corps: “Many reporters, when they go to work in the nation’s capital, begin thinking of themselves as participants in the political process instead of glorified stenographers.” The Kennedys, on the 60th anniversary of JFK’s inauguration: “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what the Kennedys ever did for your country.” His own body: “I have, of all the inglorious things, a malignant hemorrhoid. What color bracelet does one wear for that? And where does one wear it?”

I’m not sure there’s a strictly libertarian line on hemorrhoids, but the totality of P.J.’s work — his adoration of booze (when we worked together for that week in Panama, he cleaned out not only his own hotel-room minibar on a daily basis, but mine, too) and dope; his recognition that U.S. foreign-policy interventions had mostly done more harm than good; and his slapping of communism (“You can’t get good Chinese takeout in China and Cuban cigars are rationed in Cuba. That’s all you need to know about communism.”) make it plain where he stood.

For all that, I’m not sure if P.J. ever declared himself a libertarian. He seemed happier with the self-designation in his 1988 book: Republican Party Reptile, which was banned from the kiosks at the Republican National Convention partly because it contained a reprint of an old National Lampoon piece self-explanatorily titled, “How to Drive Fast on Drugs While Getting Your Wing-Wang Squeezed and Not Spill Your Drink.” It wouldn’t surprise me if P.J. liked to call himself a Republican just to savor the appalled looks from his progressive friends. He also flashed occasional signs of an inner Democrat, as when he endorsed — sort of — Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential bid. She was, he enthused, only “the second worst thing that could happen to this country.”

But it’s also possible that he influenced the Republicans more than we think. In his book Holidays in Hell, a collection of his Rolling Stone foreign coverage, P.J. thanked a long list of reporters who helped him out in his slogs through the developing world. He lovingly referred to them as “shithole specialists.” Remind you of anybody?

----------------------------------------

By: Glenn Garvin

Title: How P.J. O’Rourke Became Republican

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/02/19/pj-orourke-republican-00010199

Published Date: Sat, 19 Feb 2022 07:00:00 EST