“Governor. Stop. It’s over,” the voice broke through on the conference call line.

Six months earlier, it would have been inconceivable that anyone, let alone a mere political consultant, would cut off the most high-profile, fearsome, and feared state chief executive in the country.

It was Andrew Cuomo who was talking, after all. He was 11 years into his reign at the top of the Empire State, and just one year removed from becoming a national phenomenon for his masterful, made-for-TV COVID briefings, which offered comfort to people amidst the isolation, confusion and trauma of a global pandemic.

But on August 3, 2021 — whether he was willing to accept it or not — he was a dead man walking. That morning, the Attorney General of New York released a bombshell report that concluded that he’d broken state law by sexually harassing women staffers in his administration.

“What’s over?” Cuomo responded.

“This. All of this. This is over. There is no path forward for you,” the adviser responded.

“It’s over because I touched a woman on the back?” Cuomo shot back, his voice rising with a pitched tone of panic.

The adviser, someone not prone to hyperbole or challenging the governor unnecessarily, didn’t mince words.

“It was more than touching a woman on the back. Don’t bullshit yourself or us. If I, a man, were accused of doing any of the things you were, I would be out of a job by now.”

Silence.

“So, you’re telling me I don’t fight back? I don’t do a press conference? Why don’t I just resign then?”

Silence.

“Lis,” Cuomo started in his halting, Queens-inflected cadence, “what do you think?”

He was looking for a sympathetic voice, as he often did on calls. He had a knack for finding people who could agree with even his worst instincts. I paused before I answered.

It had taken me 17 years — and 20 campaigns — to claw my way up the political ladder and go from a lowly field organizer to one of the top communications aides in the Democratic Party. Most recently, I’d served as a senior adviser on Pete Buttigieg’s against-all-odds presidential campaign, where he’d defied conventional wisdom, won the Iowa caucuses and become one of the Democratic Party’s biggest stars. My star had risen as well.

I’d had an on-off professional relationship with Cuomo for the past three years, starting with his 2018 campaign, where I served as spokesperson and ran his debate prep. I reconnected with him at the beginning of COVID’s onslaught on New York in March of 2020, when he’d call me for thoughts on his daily briefings. Now I was a part of his kitchen cabinet — the group of trusted, unofficial advisers — that he was relying on to help him weather the allegations of sexual harassment.

While Cuomo was notoriously tough on staff, he engendered a remarkable amount of loyalty in the people around him. Yes, he could be irrational and impetuous at times, but he matched that with a deep interpersonal warmth — showing up at weddings, bar/bat mitzvahs and funerals. He always took the time to call staffers dealing with loss and personal hardships. He’d also been a formidable governor — the likes of which New York hadn’t seen in decades. He’d managed to get the unruly state legislature under control and achieve some big things.

The last several months had tested that loyalty, as it became increasingly clear that Cuomo wasn’t being straight with any of us — myself included. He’d led us down a path of defending him against claims of sexual harassment without giving us the full truth. We felt betrayed and misled.

“Governor, I’d like to disagree,” I told him. “But I just don’t see a way out of this.”

In the moment, I meant it as much for him as for me.

You might be asking yourself why, a year to the day after Buttigieg’s exit from the presidential race, I found myself on a call not with Prince Charming but with the “Prince of Darkness,” the political insider’s nickname for Cuomo.

Well, it was complicated.

It started with a cold call from him in the spring of 2018. His right-hand woman, Melissa de Rosa, gave me a two-minute heads-up before the “No Caller ID” popped onto my iPhone screen. It was a Monday night, and I was inundated with work. I needed a call out of the blue from the governor of New York like I needed an invitation to a one-year-old’s birthday party.

Some back story here: I’d worked in New York politics on-and-off since 2013, on races of every level. For elected officials and candidates like Bill de Blasio, Eliot Spitzer, Adriano Espaillat and Eric Gonzalez, among others. Still, in all that time, there was one New York politician I had never met: Andrew Cuomo.

That night, Cuomo and I spent over an hour talking about politics and governance — what they meant to each of us. We talked about our dads. His father, former governor Mario Cuomo, had passed away a couple years earlier and mine was in increasingly poor health. As the conversation wound down, he asked, “So, you’re a yes?” I told him I was a maybe. I knew working for him was a risky proposition, but risk has always been sort of my thing. Within three weeks I was on his payroll.

Not that he really needed me in that race. Even though media and political insiders took issue with Cuomo’s Raging Bull persona and tactics, it was hard to argue with the results he’d yielded as governor. In two terms, he’d racked up a list of legislative accomplishments that included marriage equality, tough gun-control laws, a $15 minimum wage, paid family leave and tuition-free college for working- — and middle-class — New Yorkers. Once he won a third term, I was off his campaign and off to the races planning Pete’s campaign for president.

We continued to keep in touch as he rode high as “America’s governor” during the COVID-19 crisis, his daily briefings broadcast live on national TV. “So, Lis-beth,” he’d ask, using his preferred nickname for me, “What do you think? How am I doing?” He rarely asked questions that he didn’t know the answer to, and the answer was evident from the fawning media coverage he was receiving: well, exceptionally well.

The hype got out of control, as it so often does. The bougie, Resistance-friendly Lingua Franca brand sold $400 cashmere sweaters hand-stitched with Cuomosexual across the chest. He won an Emmy Award for his COVID-19 briefings. He was floated as a replacement for Joe Biden on the 2020 ticket (delusional) and coronated as a front-runner for the 2024 Democratic nomination (fever dream).

He started to feel his oats. Just four months into the pandemic, he signed a multimillion-dollar book deal with Random House to tout his leadership lessons during the pandemic. It was the height of hubris. It was as if the head coach of the Atlanta Falcons had walked off the field during the third quarter of the 2017 Super Bowl, satisfied enough with his team’s 28–3 lead over the Patriots to write a book about lessons in winning the Lombardi Trophy. As everyone knows by now, Bill Belichick and Tom Brady overcame the biggest deficit in Super Bowl history to win that game 34–28. Just as the Patriots came roaring back, COVID would, too, with a second devastating wave that took the lives of 14,000 more New Yorkers — all while Cuomo was promoting his memoir.

He also began to dig in his heels about decisions he’d made early on in the pandemic, specifically the policy of returning COVID-19 patients from hospitals to their nursing homes. New York was hardly alone in implementing that policy, which stipulated that the patients had to be medically stable and that the facilities had to be able to properly care for them. Other states like New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Michigan followed the same guidance. Whether the policy was medically sound or not, Cuomo allowed the controversy around it to snowball. His administration was accused of undercounting the number of New York State COVID-19 deaths in nursing homes, attributing some of them to hospitals instead. It was a serious charge — and one that the Cuomo administration vigorously disputed, noting that they assigned deaths to where they occurred, not to where the deceased had contracted COVID. But they were slow to release the supporting data, which didn’t help their cause. At best, it was interpreted as incompetence. At worst, it was seen as a cover-up.

The crisis reached a nadir at a January press briefing during which Cuomo was confronted about the undercount. Visibly bristling, he declared: “Look, whether a person died in a hospital or died in a nursing home, the people died. … Who cares?”

“Who cares” are two words that should never come out of a politician’s mouth. Especially when it has to do with people dying.

America’s governor was quickly turning into America’s asshole. And like most assholes, he’d soon get a wake-up call. Except in his case, it was more like an air raid siren.

On February 24, 2021, a former administration employee accused him of sexual harassment. Within hours, the allegations were picked up far and wide in the media. And once again, I was getting roped in with a small group of outside advisers to help Cuomo navigate the crisis. The ask was innocuous — “just a few calls.” The assumption was that this would be a one-day story. Famous last words.

My decision to say “yes” was grounded in the fact that I believed Cuomo’s denial of the allegations, which had seemingly come out of left field. He’d been a champion of the #MeToo movement — and in those days, I’d never heard so much as a whisper about his personal conduct. Could he be flirtatious at times? Yes. Did he occasionally make jokes of a sexual nature with staffers — both male and female — at the workplace? Yes. Was he unusually into physicality as a modern-day politician? Also yes. He fashioned himself after leaders like LBJ, who was known for grabbing a lapel or 20 in his day.

The easier answer, naturally, would have been no. But politics is filled with cut-and-run artists — soulless social climbers who cling to elected officials when they’re popular, then disappear the second they’re not. I never wanted to be one of those people. I still struggled with the emotional scars of my own brush with scandal — my personal relationship with Eliot Spitzer cost me a City Hall job with de Blasio. It’s impossible to describe the isolation and hopelessness that consume you when you’re in the eye of a PR shit storm. I couldn’t live with myself if I let anyone I knew well go through it alone. Obviously, my predicament was different — I wasn’t accused of doing harm or wrong to anyone else. But in my eyes, at the time, there was little distinction.

Faced with the first accusation of sexual harassment, Cuomo swore to the crowd advising him that nothing, nothing else would come out. It didn’t take long for us to see that he wasn’t being completely truthful.

Just a few days later, a 25-year-old former executive assistant in the governor’s office came forward with New York Times","link":{"target":"NEW","attributes":[],"url":"https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/27/nyregion/cuomo-charlotte-bennett-sexual-harassment.html","_id":"00000181-dd57-def0-afb7-dfdf788f0006","_type":"33ac701a-72c1-316a-a3a5-13918cf384df"},"_id":"00000181-dd57-def0-afb7-dfdf788f0007","_type":"02ec1f82-5e56-3b8c-af6e-6fc7c8772266"}">more accusations in the New York Times. She recounted how the governor had repeatedly inquired about her relationship status, talked about how he was lonely and tasked her with finding him a girlfriend — actions that she interpreted as sexual advances.

Behind the scenes, Cuomo conceded that he had been “stupid” to engage in any personal conversations with a female staffer whom he barely knew: “I should have said, ‘This is fucking trouble.’” Still, he denied any malintent.

Like others on the team, I began to feel a sense of unease — the allegations were at the very least creepy and they showed extremely poor judgment. Aides from his early days as attorney general and governor were especially dismayed. One told me, “I’m in disbelief. He used to have a rule about never being alone with a woman in his office under any circumstances. Now he’s having these sorts of conversations with a 25-year-old? What the hell is going on up there?”

We had been told there would be no additional allegations, but here was this one — above-the-fold on the front page of the New York Times. It didn’t feel like we were getting the whole truth. And that was a big problem, not least because the number one rule of crisis communications, the most sacred rule of crisis communications, is that the person in crisis needs to be completely truthful with the people advising them. To give good advice, we had to know what other potential stories were out there.

Fool me once, shame on you.

We swallowed our doubts and tried to help Cuomo weather the storm.

Politicians had survived worse allegations of sexual misconduct — most notably, Presidents Bill Clinton and Donald Trump. On the other hand, there was Senator Al Franken, who stepped down from office in 2017 after several women came forward and accused him of unwanted touching and kissing — accusations that Franken disputed. But Democrats — including some of Franken’s colleagues who had called for his resignation — had regrets about how it all went down, questioning whether he’d received adequate due process. The complicated politics of the #MeToo debate reached a fever pitch with the media circus around Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s Senate hearings, which Democrats like Senator Claire McCaskill of Missouri blamed in part for their losses in the 2018 midterms. The hearings spurred a backlash with voters who believed that #MeToo was being unfairly weaponized for political ends.

In our internal conversations, we talked about the lessons from the Franken and Kavanaugh controversies. However, the case study we looked to the most had nothing to do with sexual harassment or misconduct: It was the curious case of Governor Ralph Northam in Virginia. In February 2019, a right-wing blog published a photo from Northam’s 1984 medical school yearbook, which they alleged showed Northam hamming it up in blackface next to a classmate wearing a Ku Klux Klan costume. Northam’s handling of the incident didn’t inspire a ton of confidence. First, he apologized. Then he denied he was in the photo at all, even as he admitted that he’d once worn blackface in a Michael Jackson dance contest. He refused to leave office.

But then a bizarre thing happened: Poll after poll showed that Black voters — the constituents political prognosticators were certain would be the most offended by the photo — believed, by a large margin, that he should stay in office. And he did. A year later, his job approval rating soared to 60 percent among all voters.

The decision was made. Cuomo would “Northam it.” He called for due process and authorized the New York attorney general’s office to conduct an independent investigation into the sexual harassment allegations. He held a press conference to make his case directly to the people of New York — one that was carried live by local TV networks across the state and every national cable news network.

We prepped for the press conference at the Albany governor’s mansion. A group of 10 of us hunkered down in the poolhouse behind the main house — feet away from the shallow hot tubs where Franklin Delano Roosevelt, as governor, had exercised his polio-stricken legs.

Everyone was on edge and exhausted. There was one main exception: the governor. He showed up to the prep session as cocky, casual and self-assured as ever. He made small talk and cracked jokes. Outside of the seemingly never-ending stream of Nicorette that he popped into his mouth, jaw tensed, you’d never have known that he was under any sort of stress.

I led the prep, looking him in the eyes as I peppered him with questions about his conduct. “Have you ever acted inappropriately toward women in the workplace?” No. “Have you ever had inappropriate relationships with women on your staff?” No. “Do you think other women will come forward?” No. Other advisers jumped in with questions and received the same forceful feedback. There’s no way he would just lie to all of our faces, we concluded. What kind of person would do that?

A week later we got word of new allegations — the most serious and shocking yet. The Times Union was working on a story about how a current employee of the governor’s office had hired a lawyer and was claiming that the governor had groped her at the Executive Mansion.

What. The. Fuck. That’s the only way to explain the reaction among the advisers, especially the women. It started to feel like we were being manipulated — used because of our gender to cover and lie for Cuomo.

“This is disgusting, right?” I asked his former communications director, who was also advising him from afar. “Did you see any of this?”

“No, it’s so disgusting,” she told me. “I don’t even know what this is.”

Another adviser was even more direct in a call with me: “He is dead. Dead. We just need to figure out how to land this plane.”

It was tempting to cut the cord right then and there, but instead we waited until we heard directly from Cuomo himself. Again, everything followed a similar rhythm. Within a couple of hours, Cuomo was on the phone with us vehemently denying the allegations. There was one key difference. I heard something I’d never heard in the governor’s voice before — fear. Genuine fear. “This is not true. It never happened,” he told us.

In real time, we could hear the most powerful person in the state of New York beginning to process that he was in real trouble. He wanted to come out guns a-blazing against the accusations. “Bad Andrew” — as staff privately called him when he got into his darkest moods — was making a comeback.

He wanted to accuse his accuser of having financial motivations. He wanted to expose her for hiring a notorious Albany-area ambulance chaser. He wanted to go after her character head-on: “If I don’t fight back, why don’t I just resign?” It took the force of everyone on the call to talk him off the ledge and convince him how disastrous it would be to go that route. We pleaded with him to show some humility and contrition.

The person who finally got him to back off was an unlikely participant on our calls: his brother, the CNN anchor Chris Cuomo. Chris was oftentimes the last bulwark against his brother’s worst instincts.

While Chris could sometimes be a dick to staff and informal advisers, reminding us: “I work in the media, you don’t” or “I know this business, you don’t,” he was far from the goon he was portrayed to be in the media coverage that ultimately led to his firing. He could be more direct with Andrew than any of us could be. He leveled with him on calls, telling him in no uncertain terms that his behavior was inappropriate, that he needed to be more apologetic and that he could never, ever come across like he was attacking his accusers. If we didn’t wrap up a call with a resolution, Chris would usually end it with: “Andrew, pick up your phone. I’m calling you after we hang up.” And he’d get his brother to agree to the direction laid out by the cooler heads around him.

I didn’t fully understand the dynamic between them. When I asked about it, one of Andrew’s longtime advisers told me how he felt the governor had lost his way a bit after his father, Mario, had passed away. According to the adviser, Andrew had become less aware of how he treated other people, and Chris had supplanted Mario as a ballast for him in that regard.

Whatever Chris said that day worked. Andrew ultimately backed down and delivered a significantly more muted rebuttal to the allegations, essentially denying them and asking New Yorkers to allow the outside investigation to conclude. It was one of the last calls we’d have as a group — no more allegations came out publicly, the AG investigation had started to move quickly and, truthfully, most of us felt pretty burned by the whole situation. The accusations had gotten increasingly more troubling: None of us were OK with enabling anyone who could have done such things.

People have asked me why I stuck around and continued to advise him, even after I started to have doubts about his conduct and the things he was telling us. It’s not like I was totally blind to the fact that political figures could lie or let me down. I’d seen the worst of politics up close. But I’d also seen the best of it. There was never a day that I showed up to work for Pete or was on a call with him when I doubted his truthfulness or sincerity. Pete had redeemed my faith in the political process and reaffirmed why I’d chosen this line of work in the first place. I wanted to believe Cuomo, I had to. To me, the other option was unfathomable: that so much of what I’d done in politics, everything I’d done for Cuomo, was in vain. That I was just another sucker, another cog in a nihilistic machine.

There was also the fog of war that came with being in the middle of a crisis of that magnitude. Every day, it felt like there was incoming that needed an immediate response — allegations of misconduct, calls for him to resign, editorials scorching him. The thought process was, “How can we get him through this?” not “Should we help him get through this?” I should’ve ruminated on the second question more.

Fool me twice, shame on me.

I didn’t hear from the governor for a number of months. He ran with the Northam playbook in the meantime. Every week that spring and summer, you could find him holding a press conference with Black clergy, community leaders and elected officials. Among the New York political constituencies, they were the most willing to appear publicly with him.

The governor reached out in June, when he received a briefing of a statewide survey that his pollster had conducted (it found that Black and women voters were the most likely to give him the benefit of the doubt). Then he reached out again in July after he’d been interviewed by investigators for the attorney general report. He called a small group of us into his office and was positively giddy about the interview: “Good news, gang,” he told us. “I sat down with Joon Kim and Anne Clark [the AG’s investigators] and there’s going to be nothing new in the report. It will just be a rehash of everything from the spring.”

He wanted to map out a prebuttal to the AG report, which he assured us would be an underwhelming document. On the docket? A letter from his attorneys contesting the objectivity of the investigators and a video, whose script he’d written out himself — a script that clocked in at over 12 minutes. It was vintage “Bad Andrew.”

The letter, which I suspect wasn’t drafted by his lawyers, included ad hominem attacks against the AG’s investigators and the previous U.S. attorney from the Southern District of New York. “Diary of a Psychopath” is how I described it to another adviser.

The video script, if possible, was even worse. It included a long section that he intended as a photo montage, where he’d show photo after photo of him kissing people of all ages, races, sexualities and genders on the face. “Governor, you should not do this,” I told him. “Unless you want this video to be mocked and replayed on the late-night shows.” There wasn’t an adviser in disagreement. The difference now, however, was that Chris, the governor’s brother, had fully extricated himself from all conversations regarding the governor. There was no one left who could close the deal with him.

In the end, none of it mattered. The AG called a last-minute 9 a.m. Tuesday press conference on August 3, where she released the findings of the report. My stomach dropped when I read the new bombshell finding from a 30-year-old female state trooper who’d served on the governor’s security detail for the last two years. She told investigators that he had touched her inappropriately on repeated occasions and made comments of a wildly inappropriate sexual nature to her on the job — a job where she was tasked with protecting his life with hers.

Once again, he’d looked us all in the eyes and lied. Once again, he denied the charges and wanted to fight them. The difference this time was that no one around him believed him anymore, myself included.

Even after the fateful call when we’d told him that his career was “over,” he tried to press on. He called each of us individually to ask our opinions, seeking a sympathetic ear or some way out of the situation he found himself in. He didn’t find one. The sole exception was former President Bill Clinton, who told him that he needed to go out and address the people of New York directly: to state that his fate was in their hands, not the politicians’. The consensus — among advisers, at least — was that unless Clinton, with his legendary political skills, was willing to do the mea culpa himself, it would do more harm than good.

For me, the AG’s report was the last in the line of crushing blows. I’d been willing to overlook Cuomo’s rough edges and obvious flaws — he’d done so much good in his 11 years as governor, and I’d seen plenty of the warm, caring side of him. But everything about the last several months had made me question my sanity and judgment. It made me wonder why I’d committed my life to a profession that was seemingly dominated by narcissists and liars. Every high I’d had had been matched by an even bigger low.

Within days, the man who had dominated Albany for the last 11 years and been floated as the next coming of the Democratic Party, announced his resignation.

“Fool me three times, shame on both of us.” —Stephen King.

Cuomo’s resignation wasn’t the end of the whole affair. Not even close. It triggered a tsunami that destroyed everything in its path. The collateral damage was almost unfathomable.

There was Time’s Up — the Hollywood-backed, post-#MeToo nonprofit that fully dissolved within weeks of the AG report’s release (its CEO and a board member had given behind-the-scenes advice to Cuomo). Then there were the former aides who were forced out of high-profile gigs — the president of the Human Rights Campaign, the largest LGBTQ+ advocacy group in the country, and the chancellor of the 420,000-student State University of New York, among others. Chris was fired from hosting the top-rated show on CNN. And just two months later, CNN Worldwide’s president, Jeff Zucker, was pushed out of his role, in part, for crossing journalistic lines in his own relationship with Andrew.

Those were the firings and resignations that made the headlines. But there was also the untold story of the dozens and dozens of people who didn’t merit an audience with the New York Times — the lower level staffers who worked in policy, intergovernmental relations, operations and different state agencies. They put up with a tough, sometimes toxic workplace because working in the office of the New York governor was a badge of honor. It was something they could be proud of and it would obviously lead all of their resumes.

Overnight, that was taken from them. Some lost their jobs, others were denied opportunities that they should’ve been given — all because of their association with Cuomo. But it wasn’t just what they lost, it was all the things they’d never get back — the years they’d wasted in his office, the life events they’d missed and the personal relationships they’d strained due to the demanding nature of working for him.

Once again, I became a target in the press for my proximity to a man acting badly. On my worst days, I convinced myself that I’d reversed all of the professional gains I’d made in the last few years. Luckily, that wasn’t the case. But it was excruciating to go through.

Say what you will about Andrew Cuomo, but he died as he lived: with zero regard for the people around him and the impact his actions would have on them.

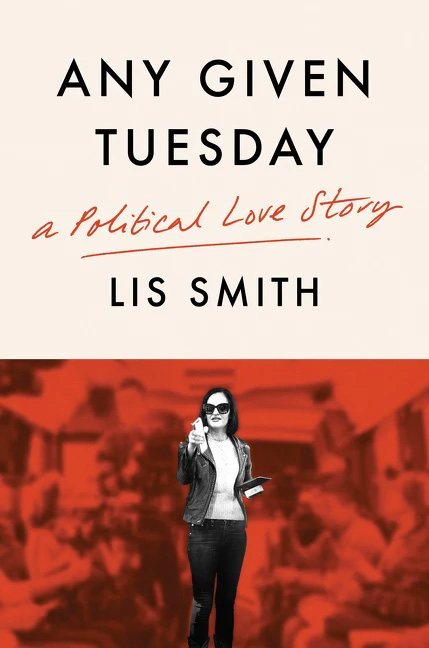

This story is an adapted excerpt from Any Given Tuesday © 2022 by Lis Smith, forthcoming from Harper on July 19, 2022.

----------------------------------------

By: Lis Smith

Title: My Time at the Side of Albany’s ‘Prince of Darkness’

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/07/08/insider-regrets-andrew-cuomo-00044317

Published Date: Fri, 08 Jul 2022 03:30:00 EST

Did you miss our previous article...

https://consumernewsnetwork.com/politics-us/mark-leibovich-doesnt-want-to-be-the-thistown-guy-anymore