In a non-descript room in a secret police station deep within a sprawling Moscow exhibition center, a Russian police officer offered Marina Ovsyannikova a cup of tea.

“For some reason, I wasn’t afraid,” Ovsyannikova told me over the phone a few days ago. “In that moment I wasn’t afraid. Now — I would think twice.”

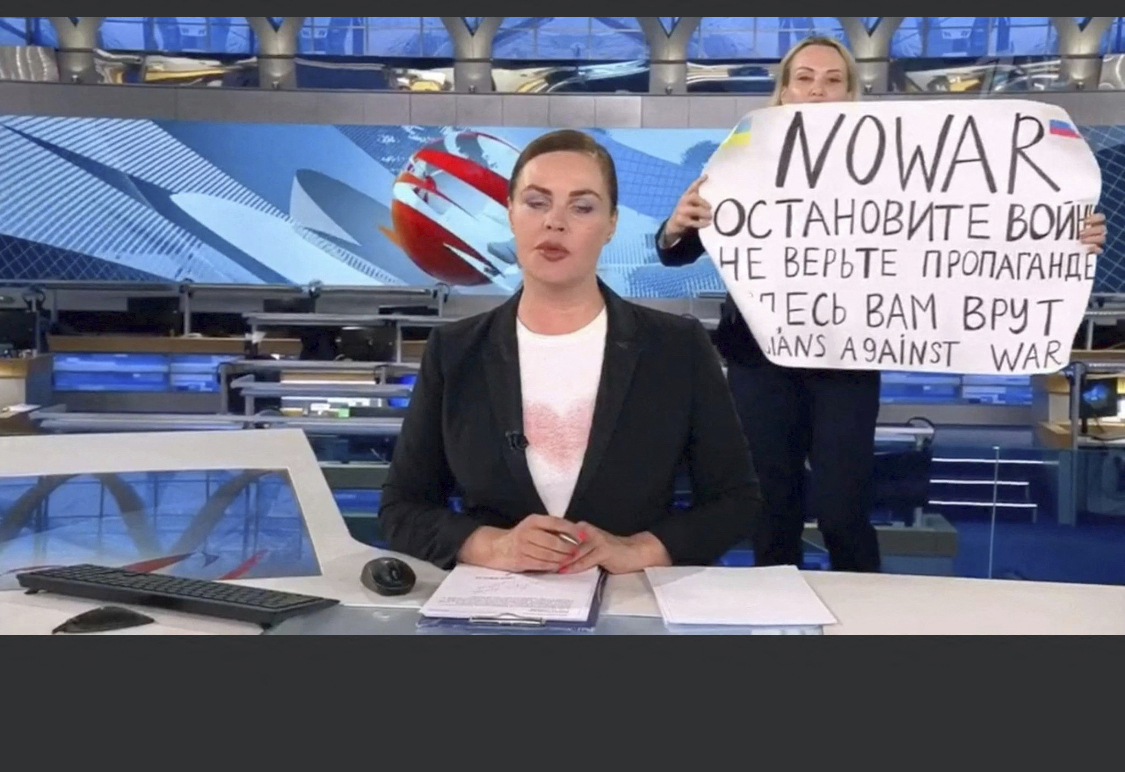

By that point, Ovsyannikova, a 43-year-old editor from Russia’s state-run propagandist Channel One TV network had already answered the same questions for hours; she was tired, hungry and thirsty. The previous night, on March 14 at 9:30 p.m., she had crashed the set of Russia’s top evening newscast Vremya wearing a necklace in the colors of the Ukrainian and Russian flags and brandishing an anti-war poster. “Stop the war. Don’t believe the propaganda. They are lying to you here,” she had written in Russian. “No war” and “Russians against war,” she’d scrawled in English. “Stop the war, no to war, stop the war, no to war,” she shouted.

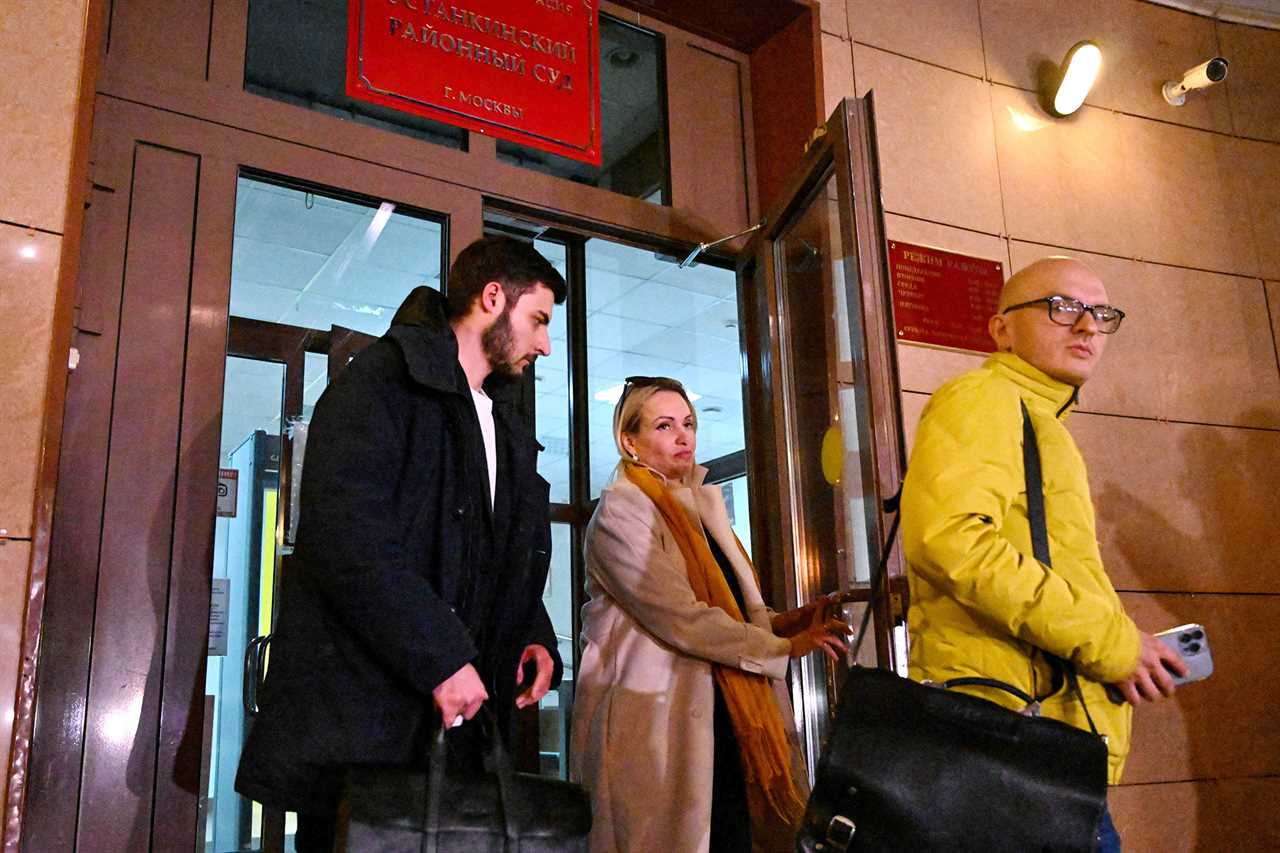

For a few moments, Ovsyannikova’s protest was beamed into homes around Moscow and central Russia. Then, the camera cut away. Ovsyannikova was detained, taken to a large police station within the state television studio complex known as Ostankino, before being moved half a mile to the secret police department within Moscow’s Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy, a large park with exhibition halls known by its acronym VDNKh, where she was held for the next 14 hours.

It was after what seemed like endless questioning, in the wee hours of the morning, that her interrogator said: “Let’s drink a cup of tea. Let’s eat some blini. Everyone’s hungry,” Ovsyannikova recounted.

As any foe of Russian President Vladimir Putin would have warned Ovsyannikova, were they still alive to do so: When a Russian security officer offers you an Earl Grey and a snack, don’t say yes. But Ovsyannikova was new to the dissident game and unprepared for what lay ahead of her.

She drank the tea.

Saved by Macron

Most visitors to the VDNKh complex, located half a mile from the Ostankino television and radio tower, are greeted by an iconic 78-foot-high statue of the “Worker and Kolkhoz Woman” and other Soviet-era relics.

But Ovsyannikova got to admire VDNKh’s true Stalinist legacy, buried deep within its walls.

“All the journalists were looking for me, all the lawyers. They were looking for me in Ostankino, where there’s a large police department. But the fact that there’s a police department at the exhibition center — no journalists knew about that. It’s a secret department, a small police station, and that’s where they took me.”

“It wasn’t the dungeons of Lubyanka,” she said, referring to the feared headquarters of the Federal Security Service (FSB) of the Russian Federation, the successor to the Soviet Union's KGB. “There weren’t any handcuffs, they didn’t torture me.”

Still, her interrogators weren’t messing around.

“They didn’t leave me alone for a second. If someone had to leave the room, a different person came in and was with me the whole time. I didn’t know, I’ve never been interrogated, so I asked, ‘Why are you following me even to the toilet?’”

Ovsyannikova was mainly interrogated by two men, she told me in our conversation — one taking the lead, the other helping out. Both were in their mid-30s, neither particularly imposing, and she had the feeling they were lackeys carrying out someone else’s bidding.

“This was not some kind of skillful interrogator from Lubyanka who is super intelligent, who is immersed in the political world," she said. The main inquisitor was “such an ordinary average Joe.”

As the men questioned her, their phones kept ringing. Ovsyannikov could hear them talk with their higher-ups, who told them how the world was responding to Ovsyannikova’s protest and subsequent disappearance as they debated what kind of charges to bring against her.

“The situation was constantly changing. … The interrogator was saying, ‘Oh, will this be administrative charges? No, it’s criminal, we’ll put you in jail,’” Ovsyannikova said. “They were watching for my reaction, and for the reactions from the international community.”

The first big moment came when Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy thanked Ovsyannikova for her protest in his nightly address just after 2 a.m. — saying he was grateful “specifically to the lady who entered the studio of Channel One with a poster against the war."

But the real breakthrough came later that morning, when French President Emmanuel Macron expressed concern over Ovsyannikova’s whereabouts, telling reporters: “We are obviously taking steps aimed at offering your colleague our protection at the embassy or an asylum protection.”

As soon as Macron made those comments, the interrogator’s phone rang with instructions to impose administrative charges, carrying a maximum sentence of only 10 days, rather than criminal ones, which could have seen her imprisoned for up to 15 years.

“I could hear part of the conversation,” Ovsyannikova told me. “I understood they were getting calls from higher management, and they were given some additional questions. Clearly, they were told what to ask me. And then the investigator was joking, ‘Oh, now Macron is calling you, something is going to change.’”

“It’s possible that Macron with his very fast reaction and offer of political asylum — it’s possible that saved me from criminal charges,” she said.

But escaping criminal charges turned out to be a different kind of punishment.

Dissident or Stooge?

To many Russians and Russia-watchers, it all seems so unlikely.

The incongruities in the story of Marina O. are mind-boggling: A veteran propagandist straight out of central casting suddenly grows a conscience and blows up her comfortable life by speaking out against a regime she spent two decades propping up. The fact she was able to burst onto the set of Vremya, Russia’s showcase evening news program, and made it to air without being dragged off by guards or dumped by a censor. The decision by authorities to give her only an administrative punishment relating to an anti-war video she posted on social media, rather than pursue criminal charges for the TV protest itself. Her lenient fine of 30,000 rubles (at that time, around $280), rather than the threatened 15-year prison sentence. The fact she was subsequently freed and free to speak with Western media.

And then, a month later, she had a new job as a contributing writer at Germany’s Die Welt newspaper (which is owned by POLITICO’s parent company, Axel Springer); Die Welt editors offered me an interview with her on the condition that I not disclose her whereabouts, certain facts about her family situation or her plans for the future. I am allowed to say that when we spoke, she was not in Russia.

What I wanted to know about her was the same question everyone who’d seen her protest seemed to be asking: Is Ovsyannikova a dissident — or a Kremlin stooge?

After Die Welt announced it had hired Ovsyannikova, a Ukrainian youth organization called Vitsche Berlin protested outside the newspaper’s office. In a statement, the activists said they were opposed to Ovsyannikova’s appointment because, “It is impossible to check whether Marina Ovsyannikova has stopped cooperating with Russia.”

“She paid a paltry $250 fine as punishment and was able to leave Russian territory unhindered. The Russian regime has already convicted several people of up to 10 years in prison for similar anti-war actions.”

“There is no such thing as ex-propaganda and no such thing as ex-propagandists,” the statement said. (Vitsche Berlin did not respond to a request for an interview.)

Ovsyannikova told me she understands the skeptics and wants to set the record straight.

On the question of why she received such a light punishment, Ovsyannikova said it was a “genius” move by the Kremlin that simultaneously took her out of the headlines and undermined her credibility.

“I am ready to do a polygraph, to answer any question,” she told me. “The Kremlin is pretty smart. They’ve thought it through, and they have a very good strategy: They are trying in every possible way to devalue my action, to humiliate me, to denigrate me, to cover me with dirt.”

“In Russia, they call me a British spy or a traitor,” Ovsyannikova continued. “To get Ukrainians to doubt me, they throw into the mix that I’m an agent of the FSB. … So I’m hated on one side and on the other — and for the Kremlin, that’s very useful. I think they’re probably rubbing their hands in glee right now, thinking about how great a job they’ve done resolving this problem.”

Of course, one of the effects of propaganda and cynical false flag operations, which Russia regularly conducts and accuses others of conducting, is that it becomes very difficult to believe anything is genuine. The point of Putin’s propaganda machine — which Ovsyannikova herself helped build — is the ambiguity and the fear. And the result is she can get on the air waving an anti-war placard, and there will be many people who believe she had sinister motives, was a pawn in someone’s game, on someone’s payroll, or part of a Kremlin operation to demonstrate leniency to anti-war protesters at a time when thousands had been jailed for far less visible anti-war statements.

Given the questions swirling about Ovsyannikova’s bona fides, why did Die Welt decide to give her a job?

“She’s a symbol of a Russian living in cognitive dissonance — knowing the Western world but living in a system which has to collapse in order to create the freedom to live in the Western system,” says Ulf Poschardt, Die Welt’s editor-in-chief. “So I think we should be open to people who decide not to be a part of the system any more.”

Many Russian journalists who have risked their lives to report about corruption and other Kremlin misdeeds, in some cases for decades, bristle at the attention given to Ovsyannikova. They don’t see why she should be praised for one act of protest when they’ve been laboring for decades in danger and obscurity — and now, in many cases, in exile.

Die Welt editors argue that if Russia is going to have any chance at evolving in a democratic direction, it will require many Marinas still working inside its power structures to make a similar mental and political break.

“And you know the German history and the history in the 20th century also. We have colleagues who spent their lives being journalists in the GDR [Communist East Germany] and who became very good journalists here,” Poschardt added.

Inside the Information War

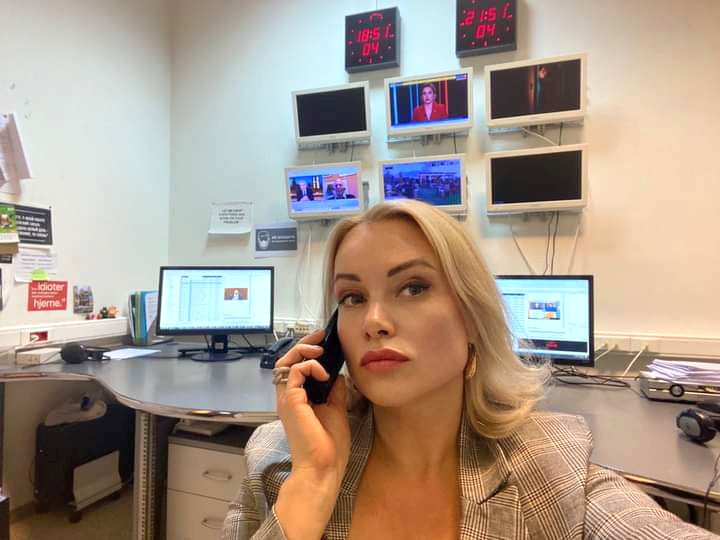

For anyone confounded by Ovsyannikova’s sudden conversion from Kremlin propagandist to truth-teller, it’s important to understand what she did at Channel One.

Since 2003, Ovsyannikova’s job was to watch Western news streams and press conferences, looking for tidbits that made the West look bad and Russia look good. As such, she was one of the few people in Russia with unfettered access to Reuters, the BBC, the Associated Press, The New York Times and POLITICO.

“In this search for information, the analysis of it, I was looking at the pictures, watching all the press conferences, you know, the [U.S.] State Department, the European Commission, all our officials, the U.N. Security Council,” she told me.

Over time, Ovsyannikova said, the gap between what those Western sources were reporting, and what Russian media like her own Channel One told their audiences, kept growing. It nagged at her. Earlier in her life, she voted for Putin. She became a journalist during what she called the “golden age” of Russian journalism, inspired by Zhanna Agalakova (who would later become Ovsyannikova’s Channel One colleague before also quitting the station herself over its stance on Putin’s war on Ukraine), Svetlana Sorokina (who now hosts a weekly talk show on under-attack independent channel TV Rain), and Alexander Nevzorov (who is facing a criminal case for reporting on Russia’s shelling of the Mariupol maternity hospital in Ukraine). But now her values were clashing more and more directly with what she was doing at work.

“I worked on the foreign desk, I saw the reaction of the other side, I saw what people said. I read the reports, for instance about [the downing of MH17]. I saw how our government is lying, and this became a symbol of the Kremlin — lies and constant cynicism. It was obvious. I was brewing in this environment, in this political, international environment, I was watching all of this. And for me, this revulsion grew over the years. And over the last years, it had grown so much that I became sick over it.”

The beginning of the end for her, Ovsyannikova says, was not the assassinations of Kremlin critics, the shuttering of independent media, or the elimination of direct gubernatorial elections. It was Putin’s move, in December 2012, to ban Americans from adopting Russian children — a decision announced in retaliation against U.S. sanctions — which prevented thousands of orphans from escaping dire conditions in Russian orphanages and finding loving families.

“We spoke about it with such cynicism on Channel One and all other government channels,” said Ovsyannikova, who was by then a mother of two young children herself. “We were so cruel. … These poor children who were already en route to the U.S. and got stuck.”

She acknowledges her role in supporting Putin’s propaganda machine: “Now I’ve gotten to the point where I understand, with horror, the injustices that have happened in our country, how it all grew, and why we kept working for state channels and continued lying.”

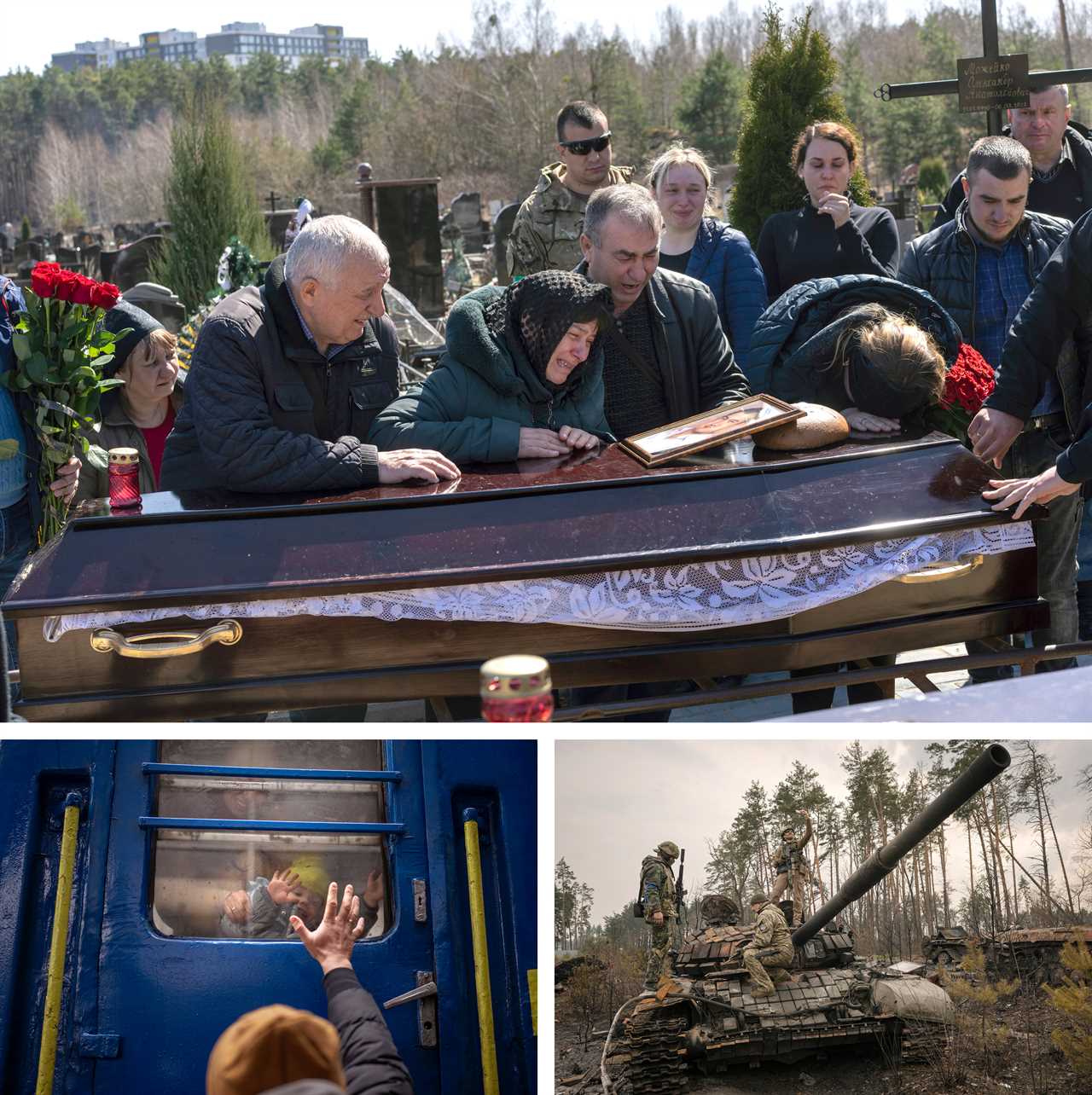

Then, on February 24 this year, Putin declared war on Ukraine. Ovsyannikova — who is half Ukrainian and was born in the southern Ukrainian port city of Odesa but spent much of her childhood in Grozny, the capital of the breakaway Russian region of Chechnya — says something broke inside her. Chechnya was the target of two Russian wars, and they turned her into an internal refugee.

“From the age of seven to around 13 years old I lived in Grozny. When the war was starting in Grozny, we heard gunshots, explosions outside our windows.” She says her mother, who was raising Ovsyannikova on her own after the death of her father when she was 5 months old, was forced to leave everything behind to flee to safety.

Putin’s declaration of war on Ukraine “was a double trigger for me,” she said. “It’s not only that my roots are Ukrainian, my father was Ukrainian, but in addition to this in my childhood I had lived through what Ukrainian refugees are living through.”

At Channel One, as with the other Russian state-run TV channels (including RT, where according to Meduza, Ovsyannikova’s ex-husband now heads up the Spanish service), editorial direction came straight from the top.

“All the instructions descended from the Kremlin,” Ovsyannikova told me. “The call comes from the Kremlin to the top guy, Kirill Kleimyonov, the director of the [Channel One] news service. … Then there are these daily morning, afternoon and evening briefings, at which they discuss what we’re going to show and in what way we’re going to present it.”

After February 24, those instructions included directives not to call Russia’s invasion of Ukraine a war. “As soon as the war started we stopped showing any footage from international news agencies, we only took footage from the defense ministry or from our correspondents on the front lines from Donetsk and Luhansk — no other clips. We didn’t show the extent of the humanitarian catastrophe, the refugees in Poland. Though I could see it on my screen, we obviously didn’t show it.”

Ovsyannikova’s first instinct was to head to the streets to protest. But as she’s told several news organizations, her teenage son stopped her, hiding her car keys.

“The idea of the protest during the live broadcast was fairly spontaneous,” she told me, and came together the day before she went through with it. She made the poster and necklace and recorded a short video on Sunday, March 13. “It was such a strong emotional impulse that I knew it had to be done on Monday, because if I didn’t do it on Monday, then on Tuesday I would just resign.”

She smuggled her poster into the TV studio rolled up in the sleeve of her jacket. When she got into work for her shift at 2 p.m., Ovsyannikova said she used her security pass to go into the newsroom, then sat looking for an opportunity.

Vremya’s host, Yekaterina Andreyeva, was separated from the rest of the newsroom by glass and guarded by security. But, Ovsyannikova says, the guard was “buried in her phone, so I realized that was my chance.”

She added: “I was 90 percent sure that it wouldn’t work. I truthfully just did not think that it would happen so powerfully and strongly. So I didn’t really think through the consequences. A lot of my friends now are blaming me for not deleting their numbers [from my phone] because they’re having problems, they’re getting calls.”

Many of Ovsyannikova’s detractors have expressed doubts that Russian news is truly broadcast live. Don’t they have a delay of at least a few seconds or minutes like many Western channels do? Ovsyannikova insists that there were so many different news broadcasts at Channel One at different times of day across the country’s 11 time zones that a delay was just impractical. Since her protest, however — the first time anything of the sort has happened in Vremya’s 54-year history — Channel One has now implemented a one-minute delay. (Numerous former colleagues and fact-checking experts have backed up Ovsyannikova’s account.)

“On every channel, all the news was transmitted live, right up until my protest,” she said. “Now on Channel One, there’s a one-minute delay, from what I know.”

She added: “People ask me why some of my sign was in English. It was really intended for a foreign audience, to show that not all Russians are idiots. … There are many people who are against the war.”

Mother Russia

In our conversation, Ovsyannikova volunteered something that she’s also told other news organizations, that she has no plans to emigrate to the West.

“Life has changed very much, of course. But I’m not inclined to emigrate. … There’s no criminal investigation into me right now, so I’m a free person, I’m a citizen of Russia.”

I asked whether Ovsyannikova is concerned about the danger she could face by returning to Moscow. After all, she hasn’t been prosecuted yet for her actual protest, and Russian authorities could decide to do that at any moment.

“They’re watching me, they’re watching every step I take,” she acknowledged. “At any moment they could bring a criminal case against me. My lawyers say, ‘You’re relaxing too soon, they could jail anyone at any moment.’”

I can’t help but remember that some journalists and Kremlin critics have faced fates worse than prison. I ask Ovsyannikova if she remembers Anna Politkovskaya, a Russian journalist who survived poison administered via a cup of tea before being shot dead in October 2006 in the elevator of her Moscow apartment building. As it happens, I interviewed Politkovskaya just five months before she was killed, when she told me, “In Russia, you can become too famous for assassination.” She’d been wrong. Ovsyannikova clearly believes fame will be a safety net for her, however.

“I’m not afraid for one simple reason,” Ovsyannikova told me. “A decision was made to hush up this situation as quickly as possible, so people forget as soon as possible and no one talks to me. ... Why am I doing these interviews? I’m doing these interviews so I have protection of some kind.”

Toward the end of our interview, I asked Ovsyannikova whether she regrets her protest.

“I wouldn’t change anything,” she insisted. “Maybe I woke Russians up a little bit, made them think a little bit about what they’re told on TV.”

“I think in many [Russians] it raised doubts,” she continued. “Because it’s one thing if you’re sitting in your kitchen and discussing with your family how the Kremlin is awful because they started this terrible war, and you feel alone and afraid. But when you see you’re not alone, when someone like me shows you there are people on TV, in the heart of the information wars, who think the same way … that’s psychologically powerful.”

----------------------------------------

By: Zoya Sheftalovich

Title: The Mysterious Case of Marina O.

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/05/01/the-mysterious-case-of-marina-o-00029150

Published Date: Sun, 01 May 2022 06:00:00 EST