Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis wants half a billion dollars to protect his state from the ravages of “extreme weather events.” Texas Gov. Greg Abbott devoted $1.6 billion toward preparing communities for increasingly devastating hurricanes.

But they still won’t say if they believe in climate change.

Even if conservative politicians can’t stomach the words, they're spending money to combat the fallout hammering their states and cities. Bracing for global warming is the rare climate issue that appeals to both Republicans and Democrats, and 34 states have done some sort of climate-adaptation planning, according to Georgetown University's state policy tracker.

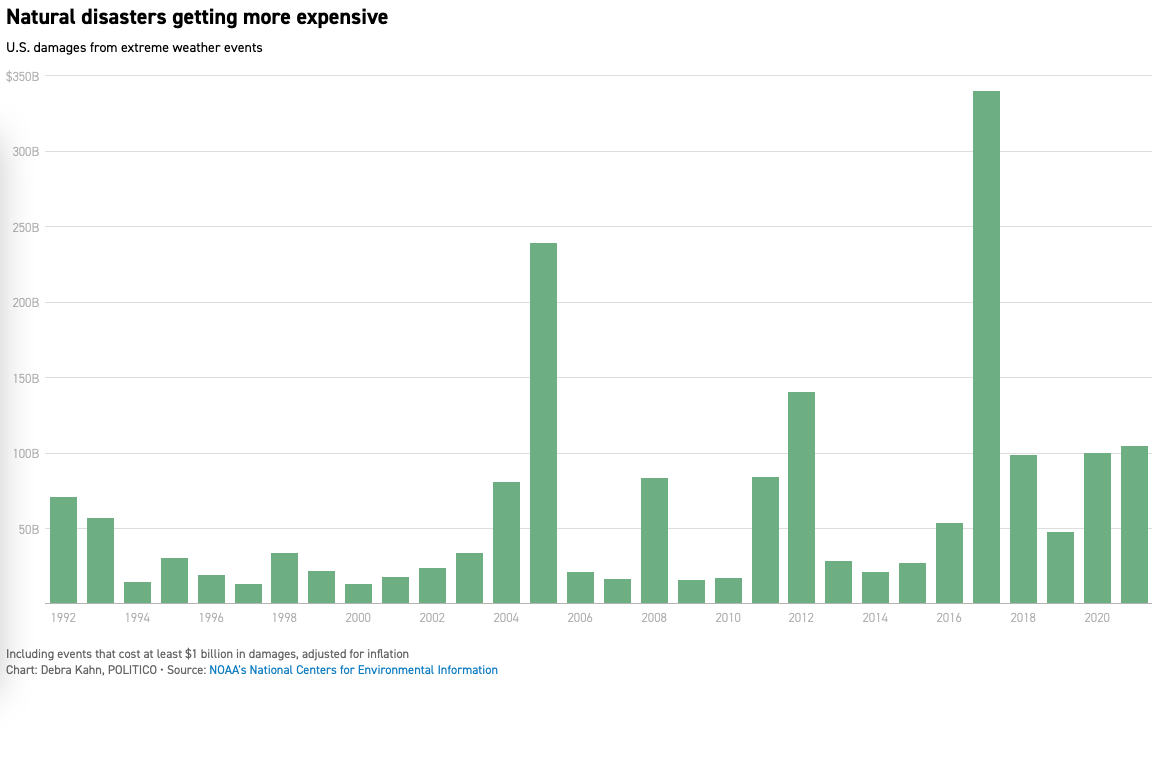

And those costs will only continue to soar as U.S. and global climate policies fall short of what's needed to stave off worsening heat waves, floods and fires. The U.S. has spent almost $700 billion on disasters in the last five years, and a federal climate assessment from 2018 estimates annual losses could reach “hundreds of billions of dollars” by 2100.

"We must do this. We have more linear miles of waterfront than any other city," said Matt Carlucci, a Republican city councilmember in Jacksonville who's making climate resilience part of his campaign for mayor. “The insurance industry will tell you that hurricanes will become more frequent and severe as climate change continues to occur."

DeSantis, a Republican aligned with former President Donald Trump, this week proposed a $500 million infusion of state funding to help local governments plan for sea-level rise and increased flood risk.

His "Resilient Florida" program has proven popular with local politicians of all stripes. Palm Beach County is using the money for a climate vulnerability assessment. Jacksonville, where the city council is more than two-thirds Republican, is seeking support for four projects, including $25 million for a new stormwater pumping station "to counter the effect of flooding and sea level rise."

"If I'm elected mayor, we will be playing for every nickel that we can find,” said Carlucci, a State Farm insurance agent who dealt with the aftermath of hurricanes Matthew and Irma and wants to get ready for more like them.

Democrats in deep-blue states often make explicit the connection to climate change. Gov. Gavin Newsom chose Sequoia National Park, where wildfires still raged, as the backdrop to sign a budget bill dedicating $3.7 billion to climate resiliency. "We're burning up as a state. ... We're the tip of the spear in terms of the consequences of our neglect to decarbonize," he said last week.

In New Jersey, Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy proposed expanding the state's "Blue Acres" buyout program for flood-prone properties after the remnants of Hurricane Ida rocked the state in September, killing 30 in floods. His Republican challenger, Jack Ciattarelli, who narrowly lost this month’s election, also supported the proposal — even as he derided Murphy's plans to transition away from fossil fuels as too aggressive.

“Climate change is real,” Ciattarelli said. “Human activity is accelerating it, and we need to do things right here and now to keep people out of harm’s way. That includes funding for Blue Acres.”

But conservative Republicans still refuse to explicitly connect global warming with what’s happening at home. Abbott consulted with a climate change-denying meteorologist ahead of the February snowstorms that forced rolling blackouts for some 5 million residents.

DeSantis dodged questions about humanity's contribution to climate change in 2019 while unveiling an executive order that established a resiliency office to address climate impacts. "To me, I'm not as concerned about what is the sole cause," he said. "If you have water in the streets, you have to find a way to combat that."

DeSantis did not mention global warming this week when he said his proposed funding would "make us more able to handle some extreme weather events."

Yet one of his appointees — Shawn Hamilton, secretary of the state Department of Environmental Protection — couldn’t help but note the money would help communities deal with the "impacts of climate change."

The political conversation in some Florida circles has evolved “to a point where we talk about sea level rise and then even climate change,” said Jim Murley, chief resilience officer for Miami-Dade County. “There was a period where they did not, but they have sort of grown out of that."

Policies don’t necessarily have to mention the climate to help adapt to it, said Bob Kopp, a sea-level scientist and a climate policy scholar at Rutgers University. “If you get people out of their hyper-political spaces, I think most people don’t want their houses to flood,” Kopp said.

Spending money on shoring up infrastructure, planting trees and bailing out property owners are relatively easy decisions — particularly when the federal government is also getting into the game, spending tens of billions of dollars on flood control, wildfire defense, property buyouts and other climate-protection measures in the $1 trillion infrastructure bill.

But it's hard to measure whether dollars spent to fortify communities against the effects of global warming are well spent, as success is often defined by avoided losses and damages. A FEMA-funded study estimates adaptation measures generally save between $4 and $11 per dollar spent, with the best bang for the buck going to upgraded building codes and the lowest going to shoring up existing buildings and infrastructure. But assessing the effectiveness of specific projects is trickier.

"It is difficult to measure something that isn’t there," said Kathryn Conlon, co-director of the Climate Adaptation Research Center at the University of California, Davis.

What types of actions count as responding to climate change is also a slippery concept. Republicans are more likely to file policies under "development," "disaster mitigation" or "resilience," rather than climate adaptation. As a result, there aren’t good figures on state spending in response to global warming.

The growing costs of natural disasters, however, are unmistakable. Extreme weather events over the past 5 years have cost the U.S. at least $690 billion, according to the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, more than double the previous 5 years. That's due partly to population growth in vulnerable areas and more assets being put at risk, and partly to the increased frequency of extreme weather.

"I do think that voters are going to reach a breaking point after experiencing more and more disasters, as well as concurrent disasters," said Jeff Schlegelmilch, director of Columbia University's National Center for Disaster Preparedness. "That will certainly help to move the needle towards incentivizing preparedness politically."

But even officials in blue states are punting on harder choices. Newsom vetoed a bill this year that would have set up a loan program to fund buyouts of vulnerable coastal properties in California, a tactic that local governments have resisted. Politicians will soon have to shift to discussing less palatable topics than how to spend budget surpluses and federal stimulus dollars.

"It might mean that somebody is not going to be able to live where they currently live," said Mathew Sanders, manager of the Pew Charitable Trust's program for flood-prepared communities.

In California, "having an extreme drought and extreme wildfires and breaking heat records all at the same time is really forcing the issue," said Rachel Ehlers, a fiscal and policy analyst with California's Legislative Analyst's Office, who noted at least 10 bills in this year's legislative session dealing with sea-level rise.

But the state’s latest draft adaptation strategy needs clearer goals, she said. "Until then, it's just random acts of restoration, really, and we don't have a sense of where we want to go and how successful we'll be in getting there."

Carlucci, the Jacksonville Republican, says he also wants the city to reduce its carbon footprint — and that he tries to convert climate-change skeptics by referring them to the "parts of the Bible that talk about what happens in the last days."

"If you don't think it's manmade, then go to the book of Revelation and take a read. It'll tell you about climate change in the last days," he said he tells them. "That pretty much closes the discussion, so we can move on and talk about what really matters. And that's making Jacksonville a more resilient city."

This story was reported and written by POLITICO reporters Debra Kahn, Bruce Ritchie and Ry Rivard and E&E News reporter Mike Lee.

----------------------------------------

By: Debra Kahn, Bruce Ritchie, Ry Rivard and Mike Lee

Title: Don’t call it climate change. Red states prepare for ‘extreme weather’

Sourced From: www.politico.com/states/california/story/2021/11/23/adapting-to-climate-is-a-winning-issue-for-politicians-even-in-red-states-1394620

Published Date: Tue, 23 Nov 2021 08:00:02 EST

Did you miss our previous article...

https://consumernewsnetwork.com/politics-us/jonathan-guyer-joins-vox-as-senior-foreign-policy-editor