Dan Coats knows firsthand what it’s like to lose a Supreme Court confirmation fight.

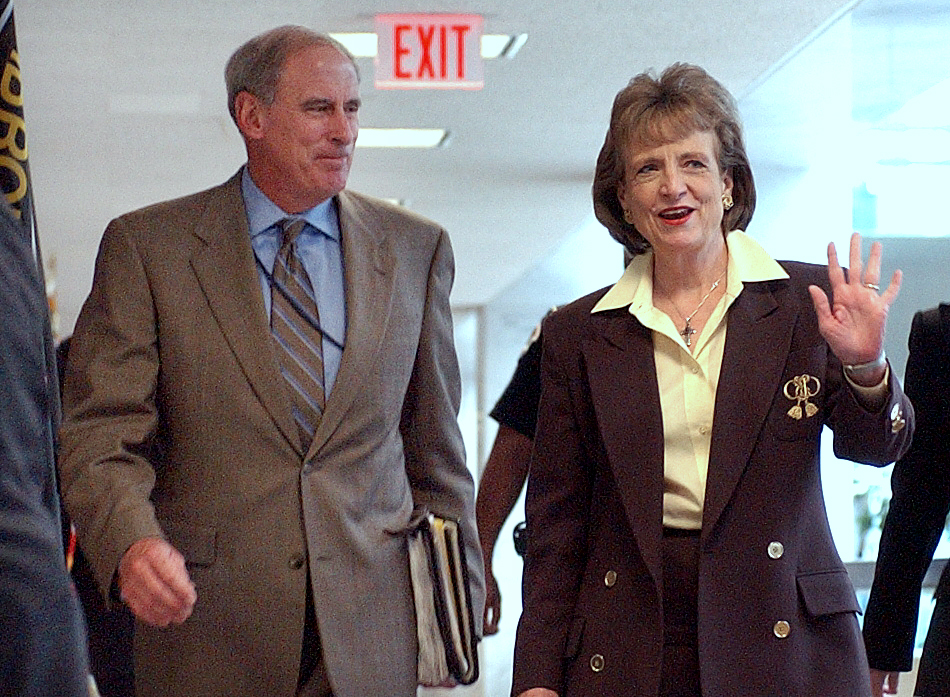

Nearly 17 years ago, he was asked to shepherd Harriet Miers, President George W. Bush’s surprise Supreme Court pick, through the Senate. Within a month, the nomination was dead.

As President Joe Biden prepares to make his own appointment — for the first Black woman to serve on the Supreme Court — it will be up to a new “sherpa” to steer his nominee to a different fate.

Under this familiar Washington ritual, it’s the job of a seasoned political hand to introduce, and help sell, a nominee to the Senate grandees who will vote on her confirmation. Usually the process sails through, or at least judders across the finish line. (This year, the task falls to former Alabama Sen. Doug Jones.) But sometimes it's not so smooth, and even the most talented sherpa can't deliver.

Coats had the ideal background for a Supreme Court sherpa. The Indiana Republican was himself a former senator and respected by his old colleagues on both sides of the aisle. He’d later do another stint in the Senate and then serve as former President Donald Trump’s first director of national intelligence.

But it’s not clear that anybody could have saved the Miers nomination.

Bush’s choice to replace retiring Justice Sandra Day O’Connor was not a typical Supreme Court nominee. Miers had never served on the federal bench and appeared to secure the nomination in large part because of her close relationship with Bush; Miers was his White House counsel and had previously worked for the president in several roles. Meanwhile, her record on policy was slim and she quickly faced vehement opposition from conservatives, who questioned her views on abortion and other social issues.

“The president has damaged the prospects for reform of a left-leaning and imperialistic Supreme Court, taken the heart out of a rising generation of constitutional scholars, and widened the fissures within the conservative movement,” Robert Bork, whose own nomination to the Supreme Court failed, wrote in a Wall Street Journal op-ed.

In an interview about Miers’ bid and the potential lessons for Jones, Coats recalled there were early signs the Miers nomination was headed for trouble.

“[There was] concern right from the beginning, because she was not gaining the support from the Republican Party that she would need,” he says. “When we began hearing things from the Federalist Society and a number of groups, and even members of our party … I thought, ‘This is going to really, really get tough.’”

Soon after getting the sherpa assignment, Coats appeared on Fox News’ “Special Report with Brit Hume.” There were no softballs, and when asked whether he had met Miers, Coats was forced to reply that he had not. The “nomination only went downhill from there,” he later wrote in a public law and policy journal article.

Coats still worked to keep the nomination afloat, introducing Miers to senators, speaking out for her, and ensuring that she knew what to expect out of the grueling confirmation process.

He remembered telling his former colleagues: “Listen, there’s more to Harriet than you think, and let me set something up so you can talk to her about it.” But, he concedes, “when you’re having a hard time getting support from your own party, it really makes it difficult.”

Miers’ lack of judicial experience quickly shone through in her interviews with senators. “It was very difficult and hard for her, and I felt very bad for her because it was really kind of throwing her into a really challenging time,” Coats says. Miers, who’s now a partner at Locke Lord, didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Bush announced Miers’ nomination on Oct. 3, 2005. On Oct. 27, 2005, he withdrew it. The Senate Judiciary Committee never even held a hearing.

Four days later, Bush nominated Samuel Alito to the Supreme Court. A longstanding member of the conservative legal establishment, Alito glided through the Republican-controlled Senate with relative ease. His sherpa? Dan Coats.

It’s an episode that Biden and Jones should keep in mind.

“It’s going to be a battle,” Coats says. “I think before you nominate, you really have to run the traps.”

A transcript of Coats’ interview follows, condensed and edited for length and readability.

What advice would you have for Doug Jones who is about to shepherd Biden’s nominee through the Senate?

The advice would be to make sure the nominee is familiar, is fully informed of the process that they’re going to have to go through to reach the finish line. And the most significant part of that is filling out a lot of forms and answering a lot of questions in writing and so forth. But also in person — honestly you don’t have to do this but I think the way we did it was needed and successful — basically being willing to sit down with any senator at their request along with their judiciary staffer or whatever and answer questions. That can be very intimidating.

You don’t want to turn down any request for sitting down with any senator. And obviously there’s a lot of preparation that needs to be done.

The distinction between Miers and Justice Alito was the difference between a president nominating someone because of their personal relationship, but not looking through and determining they could have the support to succeed, as opposed to someone coming off the bench with a lot of experience, a lot of cases dealt with, and the ability to work through the strain of getting the confirmation.

Miers, a terrific, wonderful person, very close to President Bush but not someone who had had the kind of background and experience that generally comes from nominating for the Supreme Court. And there are a lot of groups out there and there’s a lot of politics involved in terms of what type of person it should be, what type of background they should have. Harriet was in a position of not having that experience. She was a good lawyer, she headed up the Texas Bar, that says something about her and her personality and character and so forth. She was initially exposed to the nuts and bolts and the really tough confirmation process and didn’t have experience or background to deal with all the questions that would be posed to her, particularly on people who did not want to support her.

When did you know her confirmation was headed to failure? Was there a moment that stood out to you?

[There was] concern right from the beginning, because she was not gaining the support from the Republican Party that she would need. We knew it’d be a tough sledding of working through the confirmation process with the Democrats, who obviously weren’t going to stand up for her. But when we began hearing things from the Federalist Society and a number of groups, and even members of our party that this may not be somebody that could survive the process or perhaps have the experience and the values.

She did not have that experience. When we began pushing back, people from our own party [asked], “Is this the right person? A nice person, but really not the right person we want in there in the Supreme Court.” I thought, “This is going to really, really get tough.”

Finally that worked its way up to the president. He realized it just wasn’t going to work. And it’d be better for her, and better for the party in the long run to make a different choice.

What surprised you about the confirmation process?

It’s a grind. But having been a senator and having had relationships with the senators, both Democrat and Republican senators, it was easier for me to open some doors and get some support and be open to listening to the responses back, particularly from her own party, first with Harriet and then with Justice Alito. But it was consuming. I think 80 some senators requested an in person visit to their office.

Justice Alito said [before the nomination], “I just would get up in the morning and have breakfast at home and I would drive to the courthouse and I would go to my office and I would spend all day in my office pouring over cases, making decisions and going home. He said half the people at my family reunion didn’t know me. Now I’ve been thrown into this whirlwind of media, I can’t step out of the car, without 20 or 30 or 40 people with cameras and flashing of bulbs and signs saying we’ll support you or we hate you or whatever.”

It is something that most people that come through the judicial process and then are nominated have never been exposed to, that kind of media crush that was put on them and the challenge that was in front of them. So for even Justice Alito who was brilliant and had all that experience, I sat through all these interviews and he left people, even the people who opposed him, the ones who supported him were just celebrating what a brilliant career he’s had and how articulate he was in his, well, in just thinking he would make a great justice.

But I wasn’t getting that reaction early on from Miers’ interviews. It was very difficult and hard for her and I felt very bad for her because it was really kind of throwing her into a really challenging time when it was very heated in terms of who would fill that next seat.

You had experience interviewing nominees in the Senate. What was it like to be on the other side and did being a former senator help with this process and being the sherpa?

I hope I had the respect of my former colleagues and I think I did. And I think it was easier for me coming from the Senate to be respected for what I was trying to do. I didn’t try to do anything from a political side, I just took the position that no, I’m not a senator now. I’m just here to bring the nominee to you so that you have every chance to ask them whatever questions you might want to have.

Do you have any advice for the nominee Biden might pick?

Well, no. I don’t, I don’t. I’m not that much engaged in it.

It really comes straight down from the Oval Office. I was not asked if I had someone, when [Miers] stepped down. I knew that a number of other people were being suggested to the president, but I tried to stay out of that. I just wanted to be neutral.

And you had never met Miers before. How did you get chosen for this role?

I knew a little about her because she was working in the White House, and of course got introduced to her. And she was a very, very wonderful woman. And had a lot of good qualities. It’s just that she didn’t have the experience at the time, and I knew it was going to be very difficult for her.

I did everything I could to say we’ll work through this. But it became increasingly difficult, and I think she recognized that. And she may have been thinking about, “Maybe this is not where I should go,” because she understood what the challenge of that would be to survive the process.

The Senate changed its rules in 2013 and 2017 on judges to have district, circuit and Supreme Court nominees confirmed by a simple majority.

Well, it makes it easier because you don’t have to reach to the 60 [vote] level.

When you get down to needing only 50 votes instead of 60 votes, obviously of course, when it’s 50-50 and everybody holds to their own party, then it’s a real shoot out.

How much influence does the sherpa have on this process? How much influence did you think you have?

I never went there. I just felt my job was to introduce him and her and speak out for them and talk to my fellow colleagues: “Listen there’s more to Harriet than you would think, and let me set something up so you can talk to her about it.” And of course, the White House was making efforts also to get members, but when you’re having a hard time getting support from your own party, it really makes it difficult.

Is there anything you would have changed looking back on it?

I think the result here and example is that the president needs to understand the difficulty of getting a person nominated and confirmed.

I think before making a decision, a president ought to understand that we can’t make this a cliffhanger, we have to have someone who has so strong of a background and with good character and support from all different types of organizations and really respected. Because it’s going to be a battle. Every one is going to be a battle, that I’ve been through. And if you don’t have the background and experience, it makes it just so much harder.

So I would advise the president and his team: you may really like this person, been with this person, and with Harriet she was very close to the president, I fully understand why he wanted to appoint her because of the relationship. But I don’t think he fully realized how difficult it would be for her. And how difficult it would be for him to get somebody confirmed. I think before you nominate, you really have to run the traps.

And that I think even means working with leadership on your own party basically saying you know these senators better than I do, because you’re with them every day. Chuck Schumer and [Dick] Durbin and the top team, you know they really need to talk to their party people, say “OK if we go with this person, are you going to be on board and so forth?” A lot of preparation. It’s just not something you can just snap your fingers and say “OK let’s go with this guy, and I think it will work out.” You’ve got to really understand how difficult it is. And it’s not just the knowledge the nominee has, but the perseverance, and can he stand up to all the heat that’s going to be applied to him?

What do you think generally of the term sherpa for this process? It’s a term that’s also used to describe an ethnic group in a different region of the world.

I think it’s the perfect word. Because when you say “sherpa” you’re talking about climbing the highest mountain and how precarious it is and how challenging it is, and it’s the sherpa that gets you there and knows what you’re getting into and then conveys that to them before they take the first step up the mountain.

----------------------------------------

By: Marianne LeVine

Title: How to Lose a Supreme Court Nominee in 24 Days

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/02/09/supreme-court-nomination-collapse-biden-harriet-miers-bush-dan-coats-00006918

Published Date: Wed, 09 Feb 2022 04:30:00 EST