President Joe Biden arrived in Rome on Friday for a G-20 summit lacking a congressional climate mandate, and denied the chance to meet in-person with global rivals, such as China’s Xi Jinping and Russia’s Vladimir Putin.

Over the next two days, Biden must attempt to steer G-20 governments out of the Covid-19 pandemic and toward strong climate action, while helping to untangle global supply chains. His biggest barrier: unwieldy summit plenary sessions serving up a mix of in-person and video speeches.

The hybrid format in Rome offers little scope for the sort of creative climate deal-making that might help get U.N. climate negotiations starting in Glasgow on Sunday night back on track. But Biden’s in-person appearance offers him a political advantage over Xi and Putin.

“China is at a significant disadvantage because Xi is a two-dimensional image on a screen and Joe Biden is his back-slapping, lapel-grabbing, arm-twisting self,” said Danny Russel, vice president for international security and diplomacy at the Asia Society Policy Institute and a former State Department and National Security Council official. “The guy joining on Zoom can’t read the room, can’t interact, and can’t wheel and deal with others during the coffee break.”

“The G-20 has to show that it can work and deliver despite Xi’s and Putin's snub,” a senior Italian diplomat said.

National security adviser Jake Sullivan predicted “you'll see the U.S. and Europe front and center at this G-20” given the absence of Xi and Putin, telling reporters aboard Air Force One that it will be “interesting” to watch that dynamic unfold. “It's been the U.S. and Europe together driving the bus,” he said.

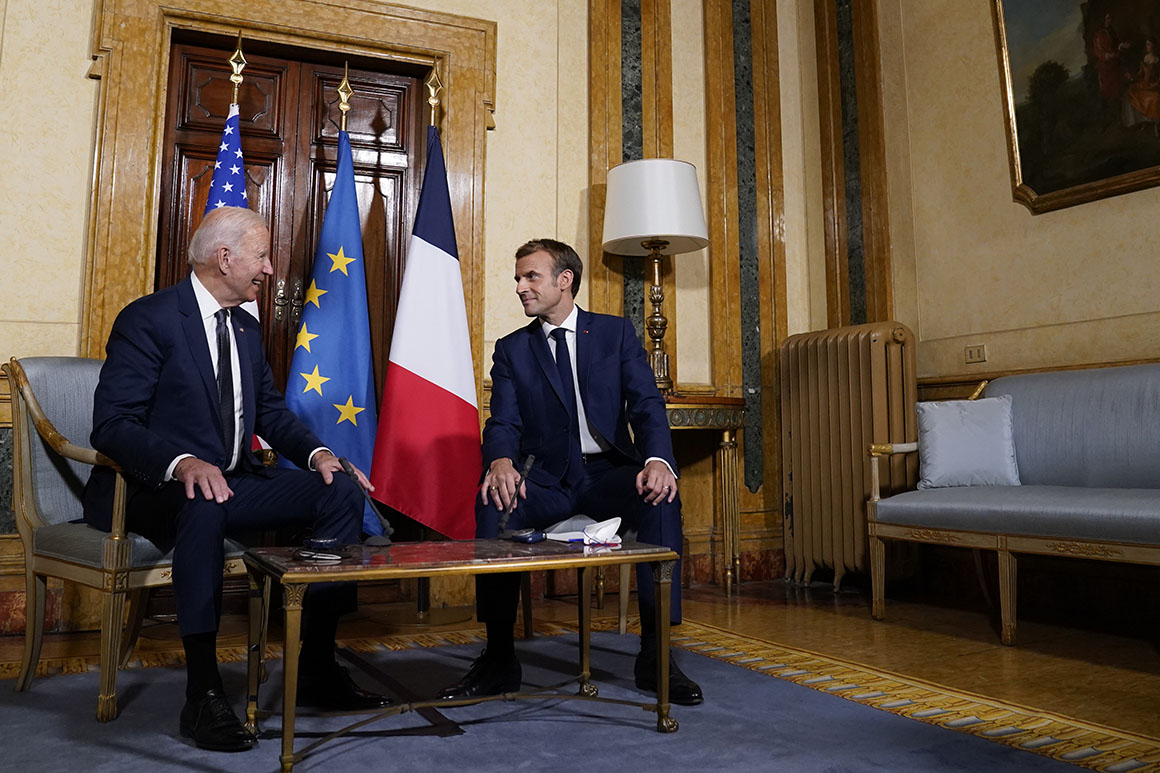

Whether the bus goes anywhere useful will depend in part on Biden being able to reach a truce with French President Emmanuel Macron when the pair meet bilaterally Friday evening. If that happens, “the G-20 is likely to further strengthen U.S. partnerships and leadership,” Russel said.

Words, words, words

G-20 sherpas are continuing to work on the summit communique.

With Covid killing more than 7,500 people daily worldwide, and preparations for the COP26 climate conference badly off-track, the draft seen by POLITICO leans heavily on expanding global access to Covid vaccines and treatments, and general commitments to climate action.

The text does not yet include language on a deal to implement a 15 percent global corporate minimum tax, which was agreed by G-20 finance ministers in October. “I am sure President Biden will make some noise on the tax deal,” said Pascal Saint-Amans, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) official responsible for shepherding the deal.

Biden’s climate problem

The Biden administration has touted its climate credentials as one of the key differences between it and the Trump administration, which withdrew from the Paris Climate Agreement in 2017.

Biden’s problem now is that Congress has not backed up the diplomacy of his climate envoy John Kerry, who has urged other countries to match Biden’s promise to halve carbon emissions by 2030 compared to 2005 levels, and reach net zero emissions by 2050.

In the absence of a national American carbon price and market, Biden will need a solid commitment from his 50 Democratic Senate votes to $500 billion or more funding for climate initiatives to remain credible this weekend, experts said. That’s the price range for funding an American transition to clean energy consistent with Biden’s targets.

A sign of how far the global climate debate has shifted in recent years: President Barack Obama’s 2009 stimulus package contained $90 billion for clean energy, at the time the largest-ever government investment in emissions reductions.

G-20 as the climate last chance saloon

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen called climate negotiations set to take place in Rome and Glasgow “a question of survival of mankind on this planet” at a Thursday news conference.

This weekend leaders will likely agree to end international coal financing, and acknowledge significantly worse impacts if governments fail to contain global warming to 1.5 degrees, but disagreements remain over what actions need to be taken to keep to the 1.5 degree Celsius goal of the Paris Agreement.

As the only venue bringing together the U.S., Chinese, Indian and Russian leaders together at an intimate level, the G-20 should have been a critical staging post for getting those climate negotiations back on track — even Alok Sharma, the British official in charge of COP26 admits that “unless we act immediately, the 1.5-degree limit will slip out of reach.”

Beijing this week released its carbon neutrality pathway — a 40-year plan to get to net zero emissions which includes raising the share of non-fossil fuels in China’s energy mix and higher reforestation goals — but it disappointed climate activists, who hoped the Chinese regime would move up the timeline on its plan to peak carbon emissions by 2030.

India this week ruled out setting a net zero emissions target. Environment secretary R.P. Gupta told reporters that because the U.S. and China are by far the biggest current emitters, setting the same date for reaching net zero emissions (most countries are suggesting 2050 or 2060) would be unfair to India.

"It is how much carbon you are going to put in the atmosphere before reaching net zero that is more important," he said, suggesting India should be allowed more time to transition, because it emits less.

Biden, meanwhile, arrived in Rome with only his existing targets, rather than detailed legislation and money to implement it. “It’s obvious that he would be strengthened to go to COP26 with something in hand,” said Senate Foreign Relations Chair Bob Menendez (D-N.J.).

G-20 success thresholds

With around half of the world’s adult population still lacking a second Covid vaccine dose, or having no immunity at all, John Kirton, head of the University of Toronto-based G-20 research group, identified five tests for leaders.

The first is to guarantee vaccination for 70 percent of the world’s adults against Covid-19 by the end 2022. The others are: approve global tax reform plans; end fossil fuel subsidies; meet a 2015 promise to give developing countries at least $100 billion annually in climate finance; and direct new IMF Special Drawing Rights assets toward poorer countries.

Canada and Germany this week published a joint $100 billion plan to provide more climate finance to developing countries.

Is the G-20 working?

Cambridge University’s Tristen Naylor, a G-20 specialist, said the G-20 squandered its opportunity to lead when the Covid pandemic hit in 2020. He described last year’s G-20 meetings as a “failure of leadership” that largely restated existing national pandemic plans.

Naylor argues that the G-20 is making progress on technocratic issues and long-standing problems like gender inequality, but is failing to confront faster-moving crises like Covid and its promise to provide “the top tier of global economic governance.”

“This was a global crisis that the G-20 could have met as a crisis committee, as it did in the wake of the global financial crisis (2008-9), but it didn't,” Naylor said.

G-20 members have delivered just 1 out of 7 vaccine doses promised to poorer countries.

The one clear success this year for the G-20 is the agreement reached by finance ministers to reform global taxation. That success hinged not on G-20 officials, but on the OECD, which brokered the deal. “The OECD is becoming the de facto secretariat of the G-20,” Taylor said.

Sunset on the Biden honeymoon

G-7 leaders could not conceal their delight at working with Biden when they met in Cornwall, England, in June. Then came the messy Afghanistan withdrawal, and wounded French pride over the AUKUS defense and trade agreement. Patience among allies is now running out.

One quality that might help keep that patience alive: experience.

Last year, 35-year-old Mohammed bin Salman — who steered the G-20 under its Saudi presidency — and a disruptive President Trump failed to lead the forum to useful outcomes.

This year Biden’s five decades of international experience, and that of summit host Mario Draghi — former head of Europe's central bank — will provide more ballast to discussion.

Outgoing German chancellor, Angela Merkel, who is preparing to retire after 16 years in office is also bringing her successor and finance minister Olof Scholz to Rome to help smooth the transition.

If this weekend’s summit falls flat, you can expect plenty of summit re-dos in 2022: “The world needs many and more summits,” to govern its biggest challenges, John Kirton said.

David Herszehorn contributed to this report.

----------------------------------------

By: Ryan Heath

Title: Missing in action at G-20: global leadership

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/2021/10/29/g-20-global-leadership-517641

Published Date: Fri, 29 Oct 2021 15:09:02 EST