I’m reposting this reminder about the massive nuclear freeze march, part of an important campaign in the 1980s. Of course, nuclear weapons are not the most salient story today, when a war rages in Ukraine, activists across the country demonstrate against gun violence, and pundits fear that every new legal move against a former president could spur another violent attack on the institutions of governance. Just for starters.

But the fairly short story of the nuclear freeze offers useful lessons for all sorts of other movements. Not the least of these is that movements (sometimes) matter, and don’t get credit for their efforts unless organizers claim it. The June 12 demonstration made international news in 1982, but is generally edited out of popular histories of the Cold War or of the Reagan era. (See if you can find anniversary remembrances in your media feed today, and tell me if I’m wrong.)

The threat of nuclear war isn’t gone, and more than a few developments in the Trump era have made it more pronounced: The United States abandoned an arms control treaty with Iran that was working, while pursuing a kind of detente with North Korea that hasn’t worked. The United States also announced that it would no longer abide by the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, negotiated in the mid-1980s, and announced that it was withdrawing from an “Open Skies” verification accord first proposed by Dwight Eisenhower, and in force for decades. Bilateral and multilateral negotiations on nuclear arms control have largely stalled. But the Russian invasion of Ukraine–which ceded nuclear weapons deployed on its territory to Russia in 1994 for a promise from the major powers, including Russia, to protect its territorial integrity–put nuclear weapons back on the agenda, and Russian leader Vladimir Putin periodically threatens to use nukes on the battlefield.

It’s an urgent moment.

The Federation of Atomic Scientists, an expert group that has promoted nuclear safety and arms control since the end of the second World War, maintains a “Doomsday Clock,” signaling its perception of the nuclear danger. In 1981, when Ronald Reagan took office and the freeze campaign took off, the clock was set at 4 minutes to midnight. In 2012, when I first wrote the appreciation below, the Clock was set at 5 minutes to midnight.

Today, the Doomsday Clock is set to 90 seconds to midnight, the closest to apocalypse that it’s ever been. Had you heard of the Doomsday Clock before reading today’s post? When first created in 1947, it was a big deal, and every adjustment–usually closer to midnight–got lots of attention in mainstream media. Now that the perceived danger is worse than ever, the Clock doesn’t seem to claim much public attention.

So:

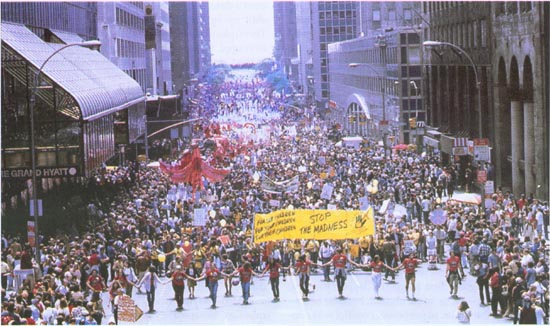

Forty-one years ago today, one million people marched in the streets of New York City to protest the nuclear arms race in general and the policies of Ronald Reagan in particular.

Organized around a “nuclear freeze” proposal, the demonstration was a watershed for a movement that seemed to come out of nowhere, not just in the United States, but throughout what was then called Western Europe.

Of course, movements have deeper roots. Relatively small groups of people have been protesting against nuclear weapons since the idea of nuclear bombs first appeared. On occasion, they’re able to spread their concerns beyond the few to a larger public. Such was the case in 1982, when Europeans rallied against new intermediate range missiles planned for West Europe, and when Americans protested against the extraordinary military build-up/ spend-up of Ronald Reagan’s first term in office.

The freeze proposal, imagined by Randall Forsberg as a reasonable first step in reversing the arms race, was the core of organizing efforts in the United States, which included out-of-power arms control advocates and radical pacifists. Local governments passed resolutions supporting the freeze, while several states passed referenda. People demonstrated and held vigils, while community groups in churches and neighborhoods organized freeze groups to discuss–and advocate–on the nuclear arms race.

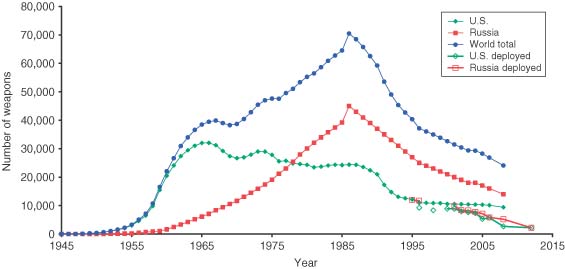

The freeze figured in large Democratic gains in the 1982 election, and Ronald Reagan ran for reelection as a born-again arms controller. Most activists didn’t buy it, but after Reagan won in a landslide, to the horror of his advisers and many of his supporters, he negotiated large reductions in the nuclear arsenals of the United States and what used to be called the Soviet Union.

US/ Russia nuclear warheads

The arms control agreements created the space in the East for reforms, reforms that spun out of control and eventually unraveled the cold war and the Eastern bloc.

The world changed.

It was both less and more than what most activists imagined possible.

Do you want to call it a victory?

Update:

The nuclear freeze movement was the subject of my doctoral dissertation and my first book

The issues in it remain relevant.

The story shows the long and complicated trajectory through which social movements affect influence. That’s the topic of my most recent book.

There are a few simple lessons that merit repeating today:

- It’s never one event, action, demonstration, statement, or lawsuit that makes the difference; rather, it’s an accumulation of efforts.

2. All victories take forever.

3. And they’re never enough, and certainly not necessarily permanent.

4. The work is important, and it must continue in order to be effective.

----------------------------------------

By: David S. Meyer

Title: Froze and Reversed the Arms Race, June 12 anniversary (reposted)

Sourced From: politicsoutdoors.com/2023/06/12/froze-and-reversed-the-arms-race-june-12-anniversary-reposted/

Published Date: Mon, 12 Jun 2023 21:06:29 +0000