TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — The ugly fight over Florida’s “Parental Rights in Education” bill has shifted from the statehouse to local school districts.

In the weeks since Florida GOP Gov. Ron DeSantis signed the measure, dubbed “Don't Say Gay” by its critics, into law, schools across the state have started to feel the legislation’s effects even before it officially takes hold.

Students have complained about being censored for supporting the LGBTQ community. One educator claimed they have been called a “groomer” and “pedophile.” At least one first-year educator was fired for bringing LGBTQ discussions into the classroom. And all the while, school officials remain in a holding pattern as the Florida Department of Education comes up with guidance for how to carry out the controversial measure.

The newly minted law, which has caused an uproar across the nation and has led to a high-profile fight between DeSantis and The Walt Disney Co., is set to go into effect July 1 and is being challenged in federal court.

“What it does create is a lot of divisiveness, and it also creates a lack of clarity completely with this bill,” Nadia Combs, who chairs Hillsborough County’s school board, said at a recent school board meeting. “I don’t know if that’s the goal of the bill, but it’s very important we do have some clarity for parents and for the schools.”

The legislation prohibits teachers from leading classroom instruction on gender identity or sexual orientation for students in kindergarten through third grade and bans such lessons for older students unless they are “age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate.”

It also requires schools to notify parents if schools help a child transition to a different gender, among other things, or any additional monitoring for their “mental, emotional, or physical health or well-being,” language expected to have a significant effect on LGBTQ student support guides that some districts use as a resource for schools and families to help support LGBTQ students and offer recommendations on how to support students to teachers.

The legislation gives parents the power to sue schools for withholding information about their children from them, putting the pressure on districts to fall in line with the law by July 1.

So far, the law has led to varying responses from local school leaders while also generating allegations of censorship from students speaking out against the measure.

At Lyman High School in Seminole County, district officials have been embroiled in a censorship dispute after planning to delay the release of a yearbook to cover up photos of a student-led protest against the bill. School officials changed their stance on the issue last week after students objected and instead are adding disclaimer stickers to clarify that students, not the school, protested the legislation.

“’Don’t Say Gay’ isn’t even a law yet and you’re already using it to target LGBTQ+ students,” JJ Holmes, a Seminole County student known as an advocate for disability rights and the LGBTQ community, told the school board last week.

In one case that has drawn national attention, the first openly gay class president at Pine View School in Sarasota County, Zander Moricz, claims his principal told him not bring up his LGBTQ activism or involvement in a lawsuit challenging the legislation in his upcoming graduation speech. School officials “had a signal to cut off my microphone, end my speech, and halt the ceremony,” Moricz said in a series of tweets detailing the experience.

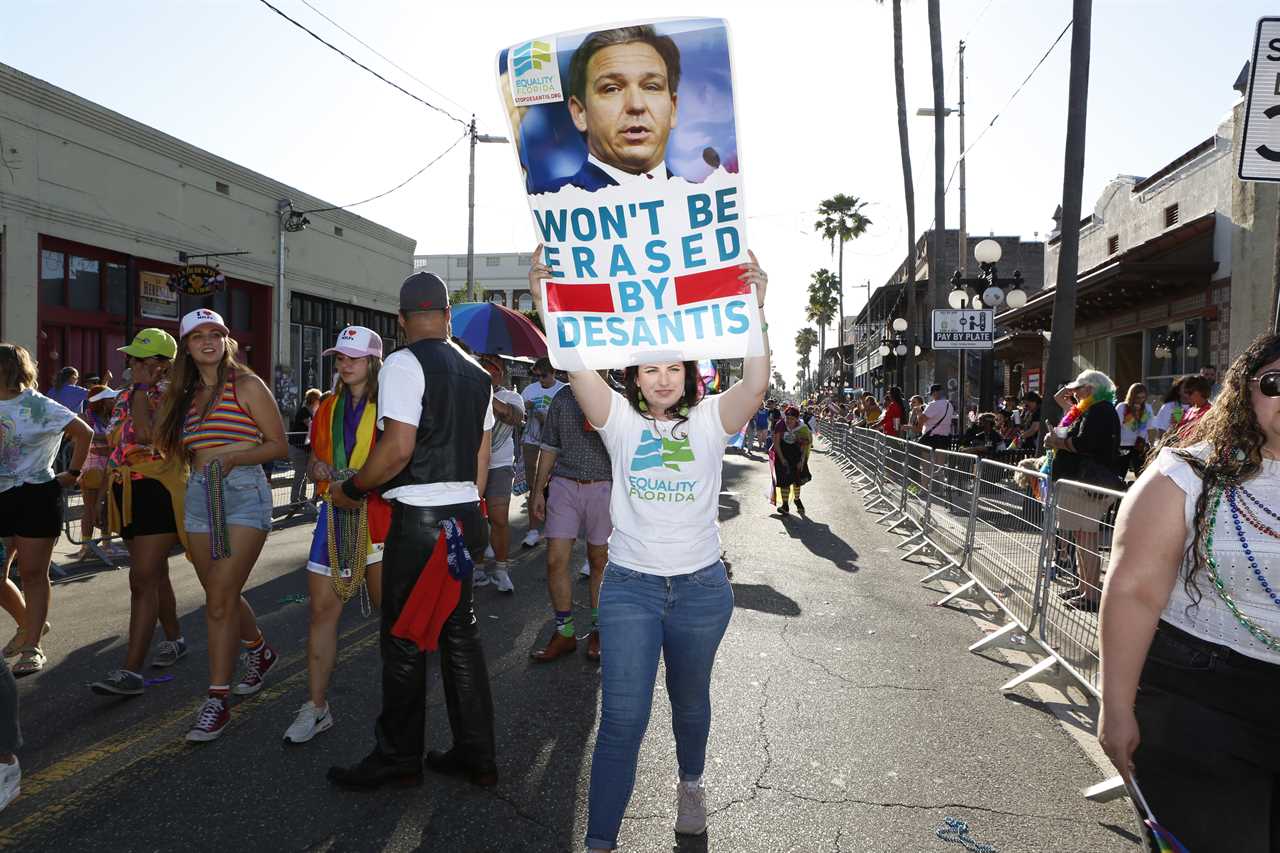

Equality Florida, one of the LGBTQ advocacy groups suing the DeSantis administration over the legislation, says that the two examples amount to “blatant censorship” tied to the bill. The organization, along with parents and students, is fighting the legislation in court, arguing it marks an “extraordinary government intrusion on the free speech and equal protection rights” in public schools.

“It epitomizes how the law’s vague and ambiguous language is erasing LGBTQ students, families, and history from kindergarten through 12th grade, without limits,” Jon Harris Maurer, Equality Florida’s public policy director, said in a written statement. “The law is driving division when we should have a state where all students are protected and all families are respected.”

Elsewhere, the new law has steered school districts to review their local student LGBTQ support guides to ensure that the policies are in line with the new state law. These guides, and particularly one in Leon County that is subject of a federal lawsuit, helped inspire the parental rights expansion in 2022 as Republican lawmakers argued that the plans can go too far to keep parents in the dark about children changing their names and transitioning genders.

In one example of attempted compliance, a Duval County board member proposed a resolution declaring that the school board “unequivocally supports” the state’s parental rights bill and “disapproves” of provisions within the district’s LGBTQ support guide. The proclamation also thanks DeSantis and the Legislature for defending the rights of parents. Duval County encompasses Jacksonville.

“These parents entrust their children to us every single day,” Charlotte Joyce, the Duval board member who suggested the resolution, said in an interview. “That the school district is knowingly socially transitioning students at school without parents’ knowledge, I really wanted that to come out.”

Joyce’s proposal drew a massive crowd at a May 3 board meeting, inspiring nearly 300 people on both sides of the issue to attend. The local Florida Times-Union described that police tape was used to create a makeshift aisle in the building while hundreds rallied in the parking lot.

Supporters of Joyce’s resolution made comments similar to statements from DeSantis backing the parental rights bill, telling the board that "school is for education, not sexualization" and “teachers should teach reading, writing and arithmetic, not ideology promoted by deviants.”

“I really don’t understand, why are you so hellbent on teaching the LGBTQ support guide to little children who barely graduated from being toddlers?” said Quisha King, a member of the conservative parental rights advocacy group Moms for Liberty.

Yet LGBTQ advocates told the board that the resolution could cause students to “hate themselves” or feel unsafe in the classroom. They asked board members to stand up to the state’s “anti-LGBTQ legislation” and implored them: “Don’t be a Disney villain.” Opponents of the parental rights bill, including President Joe Biden, say it could further marginalize some students and lead to bullying and even suicide among youth.

One educator described the stark contrast being felt by teachers compared to previous school years amid the pandemic when they were heralded as “miracle worker[s]” and “superhero[es].”

“Only recently in my eight years of teaching have I been called a groomer, a pedophile, an indoctrinator, and other names that are simply not appropriate to repeat in public conversation,” Alexander Ingram, a social studies teacher at Sandalwood High School, told the board.

Joyce’s resolution was ultimately tabled at 1:15 a.m. after more than five hours of public comment.

And in an incident in southwest Florida, one educator, a Cape Coral art teacher, was fired for bringing LGBTQ discussions into the classroom.

School officials in Lee County last month severed the contract of Casey Scott, a first-year art teacher at Trafalgar Middle School, after she taught lessons about LGBTQ pride flags and came out to students as pansexual, making some feel “uncomfortable,” the local Fort Meyers News-Press reported.

Statements from students revealed that Scott asked students to create their own pride flags in class and shared details about her personal life, like that she has a husband and girlfriend. Scott also told school officials that students had been “coming out to her,” according to the News-Press.

One student told district investigators that they “thought that was a little weird because she is telling a class of 6th and 7th graders all that."

In letting Scott go, the district said the art teacher was “not following the state-mandated curriculum,” the News-Press wrote.

While all this is playing out across the state, the Department of Education is paying close attention to how districts react to the new legislation.

Last week, state education officials called out Lee County’s school board, claiming local school officials had “conversations about ways to circumvent the upcoming requirements” spelled out in legislation prioritized by Republican lawmakers, including the parental rights law. The move demonstrates how closely the state is tracking local school leaders who in the past have bucked the DeSantis administration on reopening schools and masking students during the Covid-19 pandemic.

School districts have asked the state for help interpreting the new parental rights law and others that were passed in 2022, but so far the Department of Education has yet to meet that request. FLDOE officials said the agency is working on assistance for schools regarding the legislation and are expecting it to be released sometime before July 1.

“With so many challenges facing districts already, the last thing students need is 67 different interpretations and implementations of new laws that sometimes lack clarity,” Theresa Axford, superintendent of Monroe County, wrote in remarks to the state Board of Education this week.

----------------------------------------

By: Andrew Atterbury

Title: Florida's fight over ‘Don't Say Gay’ is getting more heated. And it hasn't even gone into effect yet.

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/2022/05/17/florida-fight-dont-say-gay-00032512

Published Date: Tue, 17 May 2022 03:31:00 EST

Did you miss our previous article...

https://consumernewsnetwork.com/politics-us/adams-top-aide-navigates-uncharted-path-on-new-york-ethics-issues