ATLANTA — Volkan Topalli had just purchased two bags of potting soil at a Buckhead Home Depot when he heard a commotion. A fight that broke out at a neighboring pool party was spilling over into the store’s parking lot. He was dialing 911 when he heard a shot and felt a searing pain in his forearm.

It was the third Sunday in May, during one of the first warm weather weekends of what many hoped would be a post-pandemic summer. After more than a year of lockdowns, Covid restrictions on public gatherings were being lifted, concerns about the Delta variant were not yet widespread and celebrations abounded. People felt more comfortable in large groups again, making way for old relationships — and old tensions — to rekindle.

Four men, all under age 20, were arrested in connection with shootings at the pool party and Home Depot. That week, the Atlanta Police Department reported 28 shooting incidents, including the one that involved 55-year-old Topalli, who’d been caught in the crossfire. The bullet to his arm shattered his ulna and left him with a wound that stretches from his wrist to his elbow.

Topalli wasn’t your ordinary victim of gun violence, however. He’s a professor of criminology at Georgia State University, so he effectively became a victim of the kinds of crime waves he’s studied for decades. The crime wave cities like Atlanta are seeing, he says, was entirely predictable.

“I'm not surprised at all that we had an increase in crime,” Topalli said in an interview. “Criminologists and public health people were saying that that was going to be the case as soon as they heard about the pandemic. And it's pretty much come true at this point.”

His shooting was part of a steep uptick in violent crime during the pandemic that resulted in a highest-in-decades peak in homicides nationwide, according to data from the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Atlanta was hit hard; the city’s police department reported a nearly 60 percent increase in homicides in 2020. Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms tied the surge directly to the pandemic, calling it a “Covid crime wave.”

But this crime wave wasn’t like those of earlier decades, which were often concentrated in big cities. The increased violent crime during the Covid-19 pandemic hit everywhere — big cities, small towns and rural areas as well. Where Atlanta and Washington, D.C., reported a steep increase in violent crime, so too did less populated places like Augusta, Georgia and Norfolk, Virginia.

Second, even as violent crimes increased nationally, property crimes and burglaries decreased.

“What the pandemic did was it shifted a lot of these patterns,” Topalli said of the difference in crimes. It owes in part, he explained, to “many more people staying at home, fewer people actually going into places of business … we've seen a drop in those kinds of crimes that we would expect would be affected by that.”

Many Atlantans, particularly those in favor of a tougher-on-crime approach, have tried to make Topalli a poster child for the city’s woes, saying crime had gotten so bad that even people studying it were becoming victims of it. But he doesn’t agree that his experience is emblematic of a larger crisis, at least not one that signals run-ins like his will become more common. Rather, he thinks of his injury as a statistical anomaly.

“I'm a 55-year-old white guy. I live in a nice neighborhood ... I know that what happened to me was absolutely ‘the wrong time at the wrong place,’” he said.

Experts have been making the case for years that keeping communities safe depends on the availability of resources that keep communities stable: affordable housing, quality education, mental health resources and child care, to name a few. The pandemic reduced or eliminated access to all of these.

That’s how many crime experts explain why violent crime increased everywhere during Covid, even if the situation was most acute in low-income communities where these resources were already limited.

“The pandemic … revealed something that most of us already knew, which was that we have segments of society that don't have the advantages of other segments of society,” Topalli said. “They're just beneath the surface and the pandemic sort of, you know, as with a hurricane … has revealed the disparities.”

This insight is motivating for criminologists like Topalli, who see the pandemic as providing new pathways for policies that could continue long-term crime reduction.

Whether city officials and other politicians can incorporate them is another question.

Crime experts cannot pinpoint one or two reasons why violence increased in 2020. But they can identify some root causes of crime that were likely exacerbated during the pandemic. As unemployment rates soared, job loss increased economic hardship. Heightened stress and uncertainty led more people to purchase firearms. Community networks and familial connections were strained.

U.S. murder rate highest in over 20 years

Homicides per 100,000 people

“You put all of that together, and I don't think you can say, X or Y was the culprit,” said Jeff Asher, a New Orleans-based crime analyst. “But I think you can put them all together and say, ‘These were the things that were the major contributors.’ And we may never know which was the most important factor.”

It’s part of why the crime prevention debate has remained largely stagnant. For decades, it has focused on two options: mitigating crime’s root causes or fighting it head-on through policing. The former poses a longer-term challenge often without immediate noticeable results, making it easier for most city leaders to invest in policing instead.

In cities around the country, addressing the crime wave has been complicated by the national debate over race and policing. The killing of George Floyd in 2020 at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer two months into the start of the pandemic added rocket fuel to arguments for and against policing as a solution to crime. Floyd’s killing, and the waves of protests that followed, raised the question of whether public resources are best directed at social services that can prevent crimes, or at policing that addresses it after it happens.

In fact, following Floyd’s murder, the argument was often framed as a zero-sum trade-off: The more funding that goes toward law enforcement to stop crime, some believed, meant that fewer resources would be made available to low-income communities of color.

Minneapolis itself is at the forefront of cities grappling with that dilemma. Amid a steep increase in homicides there, its residents will vote next week on a ballot measure that would fundamentally overhaul the city’s police department and replace it with a Department of Public Safety. The measure, which amends the city’s charter, would cut down on the number of police officers who respond to emergencies, replacing them with crisis managers, social workers and mental health experts.

San Francisco has also poured resources back into communities of color; an initiative from Mayor London Breed invests $120 million over two years into workforce development, housing and youth initiatives using money from the police and sheriffs budget.

But most major cities, including Atlanta, are leaning harder into pro-police options. Between 2020 and 2021, Atlanta’s police department received a $9.5 million increase in funding, according to the city budget. And even in the cities that saw the biggest protests against police violence in 2020 — including Minneapolis, Chicago and the District of Columbia — mayors have proposed increasing police funding for the 2022 fiscal year.

Public opinion has also shifted more in favor of increased funding for law enforcement. In October, the Pew Research Center found that nearly half of all U.S. adults — 47 percent — favor increased funding for their local police departments. That’s up from 31 percent from June 2020.

Some proponents of law enforcement reject the idea that crime prevention and policing are separate solutions.

“Law enforcement is just one aspect of public safety,” said Cedric Alexander, a past national president of the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives and consultant on crime and policing. The other aspects of public safety, he explained, are “affordable housing, good schools, availability of health care, being able to deal with homelessness in our communities, and a big one, of course, mental health.”

For its part, the Atlanta Police Foundation is trying to straddle the line between the root causes of crime and increased policing. The foundation has established four “At-Promise” community centers that offer job training, GED preparation and recreational activities as part of the foundation’s efforts in predominantly Black and low-income neighborhoods in North and West Atlanta.

The initiative provides services to between 30 and 40 students each day — about half of what it used to before the start of the pandemic, according to representatives of the Atlanta Police Foundation. Yet, those hard-fought relationships were strained in summer 2020, just weeks after Floyd’s murder, when 27-year-old Rayshard Brooks was shot and killed by an Atlanta police officer after falling asleep in his car outside of a drive-through Wendy’s. His killing set off waves of protests in the city — and damaged already precarious relationships between individual officers and teens taking part in the At-Promise programs.

“We had so much progress, you know, we were really building those relationships, and really building trust amongst our communities and our law enforcement,” said Lakeisha Walker, vice president of youth programs with the Atlanta Police Foundation. Amid citywide protests against police violence, she said, “it kind of felt like everything just fell apart.”

“Because now it's, ‘Okay, we don't trust you.’”

In Atlanta, a traditionally Black-led city that has experienced one of the nation’s highest spikes in violent crime, ongoing debates around crime and policing in the city have generated tensions between the city’s political leaders, community advocates, residents and members of law enforcement. All those factions are majority Black, making the political fault lines less about race and more about policy.

Jamal Taylor, a lead organizer with the Atlanta-based activist group Community Movement Builders, is working toward a future he hopes is police-free. The Community Movement Builders’ headquarters, a two-story house in the heart of Atlanta’s historically Black and rapidly gentrifying Pittsburgh neighborhood, sits just 10 minutes from the city’s downtown center and less than one mile from the Wendy’s restaurant where Brooks was killed.

His organization’s argument is that as long as Black communities remain under-resourced, adding more police to their neighborhoods would only further sow distrust and, ultimately, increase deadly conflict.

“What does decrease crime is being able to provide cultural resources,” Taylor said. “So people have stable places to live, so that people have food, people have stable communities and safe communities. That's what decreases crime.”

But leaders like Joyce Sheperd, a city councilmember who represents the Atlanta district that includes Pittsburgh, are more pro-police, arguing that a law enforcement presence combined with community initiatives will help alleviate crime. She sponsored legislation that authorized the city to lease land to the Atlanta Police Foundation for the construction of a $90 million, 150-acre police training facility on the outskirts of the city. The city council adopted the plan in September.

The Community Movement Builders and other activist groups protested construction of the training facility from its earliest days. It drew the ire of city leaders like Sheperd, who has been at odds with the organizing group and said their efforts were counterproductive.

“There were people who were anti-police basically saying that we should not build out a police academy ... they came and protested in front of my house on my porch,” said Sheperd.

The movement against the training facility became known as “Stop Cop City” and has grown into one of the most heated debates in Atlanta around use of municipal funds and the role of police in alleviating crime. However, because construction of the training facility is likely to take years to complete, it won’t have an impact on the current crime spike. What it will do instead, says Kamau Franklin, founder of the Community Movement Builders, is boost morale among the city’s police force after the Floyd unrest while negating the needs of the communities they are meant to serve.

“This is not just a ‘both sides’ argument around what’s the best way to solve crime,” Franklin said. “This is also about perpetuating a narrative that the police were somehow victims last year.”

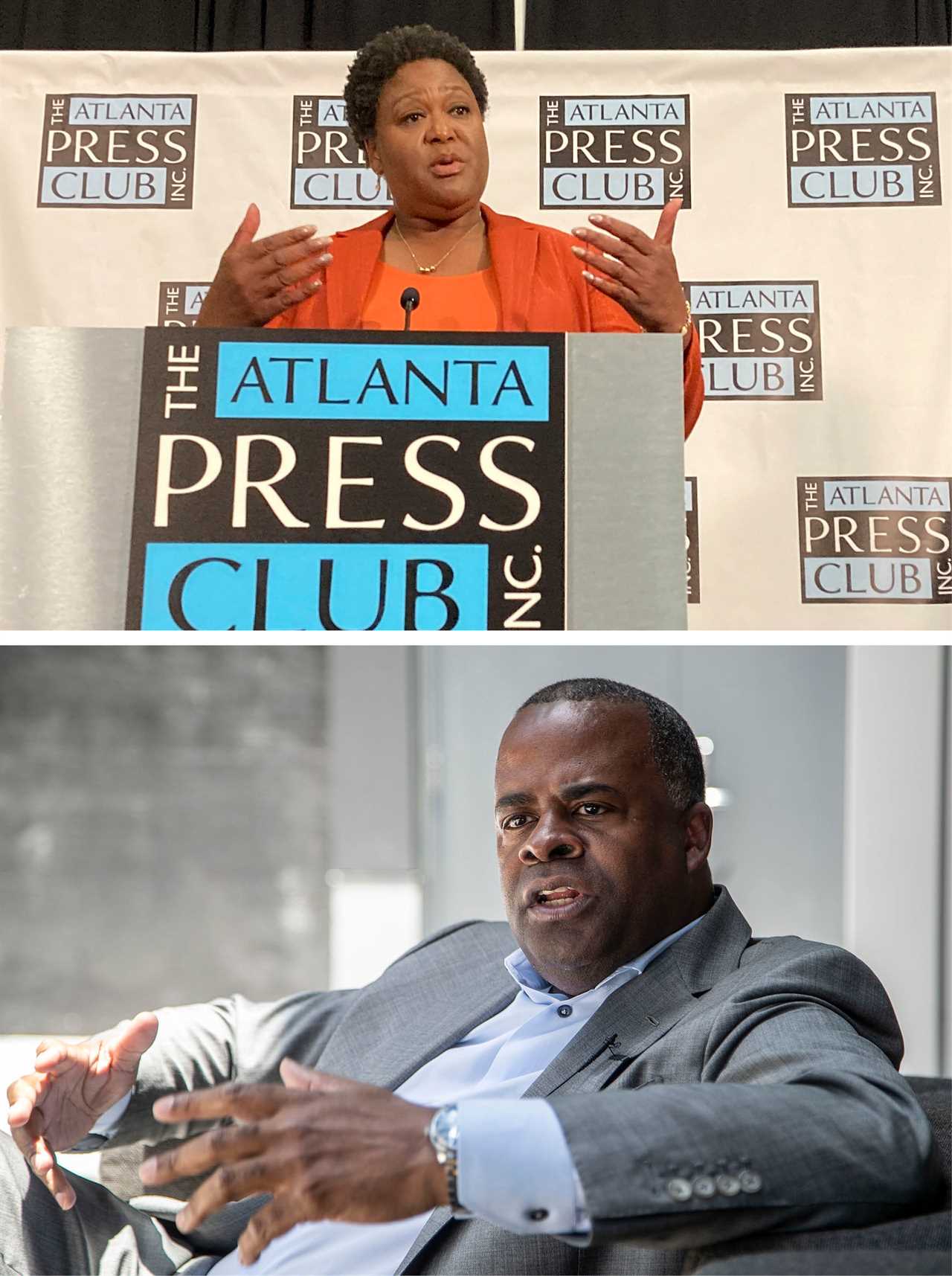

The pandemic-related crime wave is a leading issue in municipal elections across the country. Atlanta voters will choose a new mayor on Nov. 2, and the two top-polling candidates, former Mayor Kasim Reed and City Council president Felicia Moore, have shaped their campaign pitches largely around their approaches to crime.

Reed’s familiarity with Atlanta — and his relentless focus on crime — has helped vault him to the top of the candidate pool. In an interview, the former mayor called crime the “number one, two and three issues” in Atlanta “because there is absolutely no place in Atlanta that's immune from it.”

The pandemic “pushed people who are already on the margins in terms of income and employment, to have to, or to turn to, violence,” Reed said. “I don't think ‘have to’ is the appropriate word. But I think that it certainly influenced what's going on.”

Increased policing is part of his answer. His campaign platform includes hiring 750 more police officers in addition to revitalizing community initiatives. In early October, the city’s largest police union endorsed Reed for a third term.

“Anyone who says that more police don't reduce the level of crime, that's just simply not the case,” Reed said.

Also at issue are the optics associated with the uptick in violence in Atlanta, a capital city that is home to several large business hubs in a state that has become a red-hot focus of national politics. Reed’s opponent, city council president Moore, sees the issue of crime as not just an outgrowth of the pandemic in Atlanta but a long-term challenge.

Rising crime, said Moore, “threatens our city, and our reputation as a safe city and a place to come work, play and live.”

Her plan to decrease crime includes a heavier investment in courts and youth, as well as a promise to have a one-on-one conversation with at least 98 percent of the city’s police force.

“There's no one, magic-bullet solution,” Moore said. “It is dealing with the root causes, but it's also dealing with immediate action that needs to be taken to make sure we have the police presence that we need on our streets, making sure that our court system … is working appropriately and not allowing repeated violent offenders back out on the street.”

However the mayor’s race turns out, Topalli says he hopes the pandemic crime wave has helped reopen a needed debate over the causes and cures for violent crime. And with luck, that debate will ultimately expand the definition of public safety — an expansion “that opens up the room for mental health, opens up room for public health, it opens up room for things like housing, education, community partnerships,” he said.

----------------------------------------

By: Maya King

Title: First Covid raised the murder rate. Now it’s changing the politics of crime.

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/2021/10/28/covid-murder-crime-rate-517226

Published Date: Thu, 28 Oct 2021 03:30:40 EST

Did you miss our previous article...

https://consumernewsnetwork.com/politics-us/latino-dems-rely-on-padilla-for-midterm-turnout