As the world heads into the third year of the Covid-19 pandemic, U.S. and international health representatives are increasingly worried that the virus will outpace the global effort to vaccinate large portions of the world in the first part of 2022.

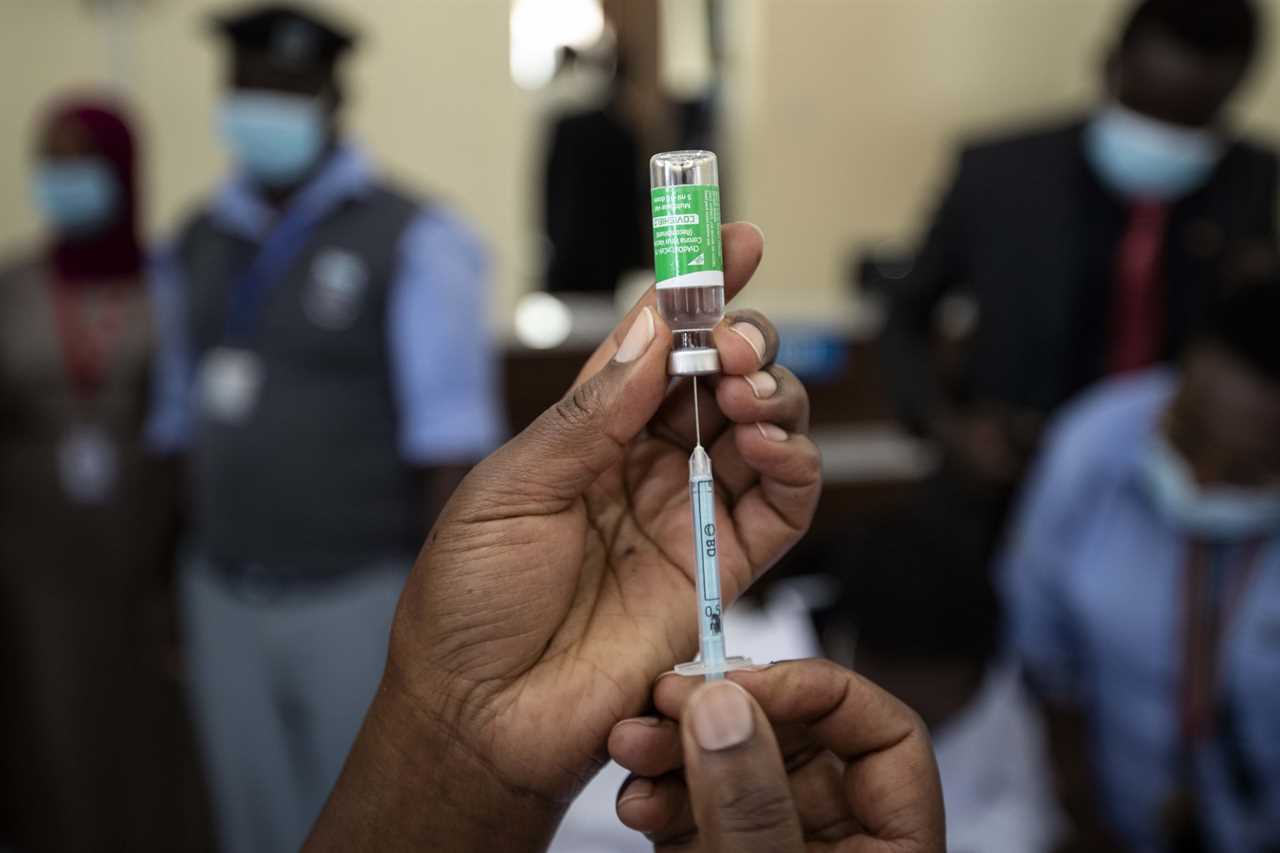

Although COVAX, the global vaccine equity effort, has secured hundreds of millions of doses for the beginning of next year, officials fear the virus will spread uncontrollably, infecting vulnerable populations, before more countries can receive and administer first doses. To date, only 43 percent of the world is fully vaccinated, with many countries in Africa still waiting for first doses. Despite initial commitments from COVAX to ship 2 billion doses by the end of 2021, the vaccination effort has fallen short, with only about 1.45 billion doses expected by January.

The delays are attributable to multiple factors, from failure to obtain regulatory authorizations for companies such as Novavax, to India’s vaccines export ban, and protracted negotiations with firms such as Moderna and Pfizer, whose substantial pledges came too late to reach low- and moderate-income countries.

Now, as case numbers and hospitalizations have begun to surge again in Europe, top Biden administration officials and international health groups are scrambling to find ways to deliver and help facilitate vaccinations in low- and middle-income countries in the next several months.

“We’ve been exploring options to be able to get the companies to significantly increase their capacity specifically for the development of doses that can go to low and middle income countries,” Anthony Fauci, the president’s chief medical adviser, told POLITICO. “This is to get pharmaceutical companies, particularly those that are making mRNA, since that's the most adaptable one, but anybody really, to increase capacity to get doses to low- and middle-income countries quickly as opposed to a program that starts in 2023.”

In a series of meetings over the last three weeks, White House and Covid-19 officials have worked to finalize two deals — one that would facilitate the delivery of hundreds of millions of Moderna doses to COVAX and another that would significantly expand the manufacturing capacity for both Moderna and Pfizer to help create supply for the rest of the world, according to two individuals with direct knowledge of the matter.

But those deals won't generate significant new doses until the latter part of 2022. In the meantime, officials are grappling with a more immediate setback: A partnership between Johnson & Johnson and Merck to accelerate vaccine production now may not generate any usable shots until the spring, two people with knowledge of the matter said.

That new timeline, which has not been previously reported, is months behind the schedule that the Biden administration laid out when it first hailed the government-brokered partnership as a "historic manufacturing collaboration." And it means COVAX will need to find alternative ways to fill that gap.

Exports from India of AstraZeneca’s vaccine doses produced by the Serum Institute are expected to restart this month, filling part of the shortfall. The world will instead largely rely on Pfizer and G-7 countries to begin delivering on their promises of 2 billion doses by the end of 2022 at the start of next year. Senior Biden administration officials are confident Pfizer will significantly ramp up the number of doses it makes available for international distribution at the beginning of next year. But it is still unclear whether other wealthy western countries, particularly those in Europe, will increase their shipments at a pace that matches the U.S.

The concerns raised by officials underscore the degree to which the world still faces significant complications in vaccinating enough of the world to keep Covid-19 at bay and to prevent new, more-transmissible variants from emerging. From convincing the globe’s wealthy nations to donate more doses and faster, to purchasing doses directly from pharmaceutical companies, to ensuring countries have the ability to administer shots, COVAX still faces roadblocks to distributing the shots equitably and efficiently across the globe.

“We’re seeing huge disparity in the availability of vaccines to high-and low-income countries, which is pretty scandalous,” said Lily Caprani, head of advocacy for health and pandemic response at UNICEF. “ We live in fear of an outbreak or a surge in one of those countries because it would be a disaster for their health system and is the kind of place where … another variant can emerge.”

In a statement to POLITICO, a White House official said the administration is just “getting started” on its work to help vaccinate the world.

“We … will not rest in our efforts to lead in global COVID-19 response,” the White House official said. “We need other countries and companies to embrace the same urgency and wartime spirit that the United States have, and push every day to make that a reality.”

To date, the world has only administered about 7.6 billion shots, according to data collected by Bloomberg. Health experts have said 11 billion doses are needed to crush the Covid-19 pandemic. So far, COVAX has secured eventual commitments for 5.5 billion doses. But it has shipped just 510 million to countries across the world. Meanwhile, the U.S. and other nations have shipped only about 450 million. It’s not immediately clear to health advocates how much those two tranches overlap.

The deficit follows months of repeated warnings by the World Health Organization and COVAX that there could be disastrous consequences if wealthy nations continued to hoard doses and if poorer countries could not access vaccine supply.

Despite the call for more help to vaccinate the world, COVAX last year struggled to build sufficient stockpiles of Covid-19 doses and raise funds to erect the infrastructure needed to help put shots in arms. COVAX has downgraded its vaccination targets. And last week, the WHO said it needs another 550 million doses to help reach its goal to vaccinate 40 percent of every country’s population by the end of 2021— a target it could miss if COVAX and its partners do not obtain the promised doses quickly enough and if host countries do not quickly administer them.

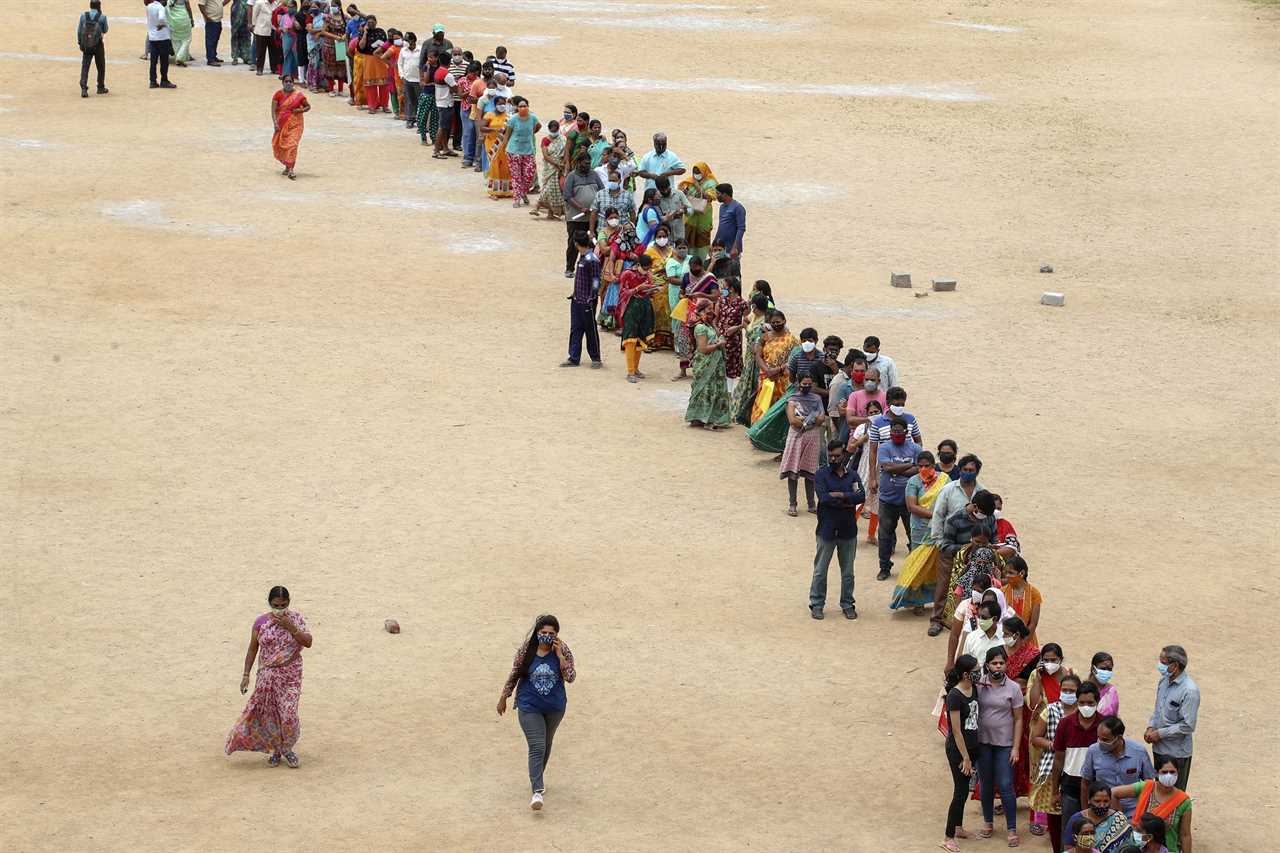

Even if the world had enough supply immediately, officials say it would still face problems getting shots into arms because many countries either do not have the ability to distribute doses locally or because their populations are not signing up for the jab.

“To get 70 percent vaccination globally next year … there's a supply piece to that and there's a capacity demand side to that. If either of those falls short, it slows you down,” one senior USAID official told POLITICO. “We need to be keeping those two tracks running and growing in parallel to each other so that as the supply continues to increase the ability of countries to absorb that and get those jabs into arms increases. The problems are most acute in the lowest income countries and in the fragile countries — those are places where we're going to have a lot of work to do in the year ahead.”

After nearly a year of trying to convince wealthy countries to do more to help the world reach the 70 percent vaccination target set by the WHO, the world is beginning to see the formation of another virus surge in Europe and officials fear Covid-19 will spread to other non-vaccinated populations across the globe.

“You look at the surges [Europe is] seeing now ... there are certain elements that seem to characterize the appearance of a surge,” Fauci said. “Those countries that have greater than 77 percent of their population having received at least one dose, there really is not very much of a surge being seen. Whereas in those countries that have a lower level of vaccination, you see an absolute clear cut surge.”

* * *

The fear over getting shots into arms quickly stems from decisions made by wealthy countries in 2020. When the vaccine first became available, the U.S. and many countries across Europe scrambled to gobble up the supply from pharmaceutical companies they helped fund to develop a vaccine. For months, those countries worked to secure enough doses to inoculate the majority of their populations before considering international donations and vaccinations for poorer countries.

“COVAX was an afterthought,” a senior Biden administration official working on the federal Covid-19 response said.

Now, Caprani said, those same wealthy nations are engaged in another race against time, confronting the need to inoculate as many people around the world as possible before rising hospitalization numbers turn into deaths and before another, more dangerous variant comes along.

The stakes are not new, Caprani and other global health experts said. Since the beginning of 2021, when the vaccine first became available, they have warned about what could happen if countries in Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia did not receive first doses at the same time as rich countries.

After securing enough first doses for their populations, wealthy nations began making pledges this spring to eventually deliver large quantities to those countries. But rich nations and the pharmaceutical companies they support have done little until recently to quickly supply vaccines to low- and middle-income countries that lack the resources to fight Covid-19.

“COVAX was set up [in the spring of 2020] to overcome a problem we could all see coming down the track, which was that the only countries that were going to get vaccinated and get out of the pandemic were those with the buying power,” Caprani said. “COVAX was supposed to help us overcome that. It raised a lot of money and a lot of political will … and then just could not get the supplies. And that has been so deeply frustrating to everyone.”

And while that problem has been the international community’s to address, the Biden administration has in recent months come under increasing pressure to address supply shortages.

The U.S. so far leads the world in vaccine donations. It has delivered more than 250 million doses — more than all countries combined, according to data compiled by UNICEF. Yet the administration is under scrutiny not only from low- and middle-income countries but also from advocates at home who say the U.S. should not move forward with a massive booster rollout domestically before more of the world receives first doses. Others note that the U.S. has not put enough pressure on American pharmaceutical giants to share their technology with the globe so others can step up their own vaccine production.

“Every day, there are six times more boosters administered globally than primary doses in low-income countries. This is a scandal that must stop now,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus told reporters on Nov. 12.

Those criticisms date to the spring of 2021, when the U.S. had amassed enough of a domestic stockpile to meet vaccine demand in the country but moved slowly in shipping doses overseas.

Despite the significant number of doses the U.S. had on hand, top White House and health officials debated the merits of diverting U.S. doses to the world at a time when the majority of the American population was not vaccinated and the country was struggling with vaccine hesitancy.

White House officials feared the U.S. vaccine donations would cost too much — and that the optics of giving doses away while the virus raged at home would hurt the president politically. Officials also raised serious health concerns about what the Biden administration would do if another surge emerged and there were not enough doses for those seeking inoculation.

“There were several weeks of debates over whether to give some of our own doses to other countries,” one senior administration official said, referring to discussions in the spring of 2021. “There were several competing interests. Some people didn’t think we could do both … donate and vaccinate here. At that time, we also hadn’t convinced people in the U.S. to get the shot.”

During that same period, India experienced a massive surge due to the Delta variant. Official figures vary, but some estimate that as many as 400,000 people died. The actual number is likely much higher — possibly in the millions, according to India’s excess death data. At the time, India pleaded with the U.S. for vaccine doses. The Biden administration pledged some of a 60 million AstraZeneca tranche to India but by the summer — months after the country’s initial surge — few had arrived. The Biden administration did expedite the shipment of oxygen and testing supplies.

“There was a feeling that by the time we could actually get India doses, the surge would have already passed,” a second senior administration official told POLITICO. “It was easier and more impactful to deliver things like oxygen.”

By June 2021, under pressure to help the rest of the world, the Biden administration announced that it would send 500 million Pfizer doses to the world but that the majority of them would not arrive until 2022. It also laid out a plan for sending doses to countries immediately from its stockpile, but the total amounted to just 80 million — a fraction of what was needed to help quicken the pace of vaccinations in poor countries. The administration promised those doses by the end of the month. Weeks later, though, after only sending 20 percent of what it had promised, the White House revised its pledge, saying it would only allocate those doses to countries across the world by that time, not ship them.

When the donation shipments began later in the summer, they moved slowly. A few million at a time made their way to an assortment of countries in Southeast Asia, the Caribbean and Latin America. Only 15 million were allocated for countries in Africa, home to some of the world’s most populous nations.

At the same time, the world was counting on deliveries from Johnson & Johnson, whose one-shot vaccine was easier to administer than the two-shot regimens of other manufacturers that had obtained Food and Drug Administration approval, but an incident at an Emergent BioSolutions manufacturing facility in Baltimore stalled production. In March, the contractor accidentally botched 15 million doses of the vaccine by mixing it with the AstraZeneca drug substance. That prompted the FDA to halt production for several months while investigating.

Shortly after the administration began delivering tens of millions of the Pfizer doses in the 500 million package, it struggled to get Moderna, a company that had received billions of dollars in investment from the federal government to produce a vaccine, to sell doses to COVAX at cost.

A deal struck by the Trump administration’s Operation Warp Speed had limited the government’s ability to share the Moderna doses it bought with the rest of the world. According to multiple individuals familiar with the Moderna negotiations, the company had made it known to Trump officials that it was against selling its vaccine to countries at a not-for-profit price.

When the Biden administration came into office, officials on the White House Covid-19 task force tried for months to convince Moderna to rework its contract and allow the federal government to more easily send its shots overseas and to strike a deal with COVAX to sell its product at a low cost.

In May, Moderna and Gavi finalized a deal for 500 million doses for COVAX, albeit with only 34 million of those to be delivered by the end of 2021. COVAX is still waiting for the shipment.

“They’re in the process of starting [to deliver the 34 million],” said Seth Berkley, the CEO of Gavi, the organization overseeing COVAX. “Some of it is now and some of it hopefully is going to move up a little bit in time.”

Still, the White House has pressured the company to do more.

U.S. officials now are nearing a deal with Moderna to pledge millions more doses of its vaccine to COVAX at $7 per dose — a price lower than what the company gave the U.S. and other wealthy nations. While the total number of doses is not yet finalized, officials have already signaled they expect Moderna to eventually set aside even more of its supply for low-income countries.

Meanwhile, Moderna has continued to resist pressure to share its vaccine technology with the world, limiting the ability of low- and middle-income countries to make doses for themselves. Under its deal with the federal government, Moderna owns the lucrative technology critical to the vaccine’s success, despite its reliance on years of taxpayer-funded NIH research. Pfizer also has also not shared its vaccine recipe with the world.

Last month, Moderna pledged to set up an mRNA manufacturing facility in Africa that would help the continent more easily access doses. But the company has offered few details about the plans for that operation, including how many doses will be manufactured and where the hub will be located.

“For the life of me, I cannot understand why we are beholden to this company,” Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.) said in a House Appropriations Committee hearing Nov. 17. “People are dying, time is of the essence and in the midst of it all Moderna is making billions of dollars controlling vaccine production.”

César Sanz Rodriguez, Moderna’s vice president of medical affairs for Europe, Middle East and Africa, told reporters Nov. 18 that the company plans to deliver between two and three billion doses, at least 1 billion of which will go to low- and middle-income countries. But those doses, like most of the shots it sold to COVAX, will not be available until some time next year.

As the Biden administration and other health advocates have scrutinized Moderna for not doing enough to help vaccinate low- and middle-income countries, the company has said the time constraints it was under to develop the vaccine in part curtailed its ability to help step up vaccinations across the world.

“A year ago, we had the ambitious goal of producing up to 1 billion doses at our own facility, supplemented by partnerships. To date, more than 250 million people have been vaccinated globally with the Moderna Covid-19 vaccine,” Stéphane Bancel, the company’s chief executive officer said in a press release Oct. 8. “We recognize that our work is not done. We are committed to doubling our manufacturing and expanding supply even further until our vaccine is no longer needed in low-income countries.”

* * *

The Biden administration’s scramble to line up additional doses has so far done little to win the confidence of activists who warned in the pandemic’s earliest months that the U.S. needed to take aggressive measures to prevent the rest of the world from falling well behind.

“The vast majority of the population outside of the highest-income countries have yet to receive a first dose, and that deplorable status quo is going to continue,” said Asia Russell, the executive director of Health GAP, the Global Access Project.

Russell and others have pushed the administration to take a far more confrontational stance with vaccine makers, arguing that a quick end to the pandemic hinges on forcing companies to share their vaccine patents and formulas widely.

“It’s too slow,” Russell said of the administration’s current efforts to coax voluntary donations out of Pfizer and Moderna. “And this is a race of vaccines and therapeutics against variants.”

Joia Mukherjee, chief medical officer at Partners In Health, the Boston-based nonprofit founded by Dr. Paul Farmer, suggested that Biden should invoke the Defense Production Act to compel Pfizer or Moderna to share their technology with other U.S. experts, who could then provide the information to lower-income nations.

“These experts would then distribute that know-how themselves to capable manufacturers around the world, similar to how they have transferred technology globally for flu vaccine,” Mukherjee said.

The White House has insisted that the Trump-era contract the government signed with Moderna prevents it from compelling the company to share its vaccine recipe — limiting its ability to force a transfer of technology or replicate the shot on its own.

"We have had dozens of lawyers across the federal government review the Moderna contract," a White House official said. “They have made clear to us that the [U.S. government’s] contracts with Moderna do not provide the USG sufficient information, technology and human resources required for the USG to produce the vaccine itself or have it manufactured by an alternative source.”

Pfizer never participated in Operation Warp Speed, the official added, allowing it to retain full rights to its own vaccine recipe.

Meanwhile, Biden officials say there are situations largely out of the administration’s control, such as vaccine production lags and distribution roadblocks, that limit the ability for the U.S. and COVAX to not only ship doses but also to ensure shots get into arms on the ground.

The U.S. and the world has for a year waited for Maryland-based Novavax to bring its vaccine to market. The vaccine is key to the global vaccination effort because it is easy to move and store, unlike the mRNA vaccine products. Novavax, which received $1.6 billion in federal funding, produces the vaccine by using bug cells to produce spike proteins. The process is familiar to scientists but it is often difficult to scale. As of the end of last month, the company was still struggling to prove to the FDA that it could manufacture its product with the highest degree of quality on a consistent basis and at scale.

Since then, the company has finished filing for emergency use authorization in several countries, including the United Kingdom and Europe. And its authorizations have been approved in the Philippines and Indonesia. But it is unclear whether the company will receive approval in markets that would allow it to deliver on a mass scale.

In addition, the Biden administration was hoping that a manufacturing deal between Johnson & Johnson and Merck would lead to products being delivered by the end of 2021. But that manufacturing process has taken longer than expected to ramp up, marking the latest setback for a one-shot J&J vaccine that officials once saw as critical to ending the pandemic in harder-to-reach parts of the world.

Beyond vaccine-production lags, the world faces a major hurdle to help countries that receive donations to get shots into arms before the shots expire. Some countries in low-income regions do not have the financing or the public health infrastructure to set up a vaccine drive.

Berkley told POLITICO in an interview that between 18 and 25 countries are struggling to absorb doses.

“We’re going to, if necessary, slow down deliveries for those countries because you don't want to overwhelm them and have doses go to waste,” he said, adding that some of those countries are in conflict or are experiencing significant vaccine hesitancy, including Chad, the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Haiti had to return some 250,000 Moderna doses it received from the U.S. this summer because it couldn’t use them before they expired in November due to the island nation's multiple problems, from political instability to natural disasters.

Berkley said COVAX needs between 300 million and 900 million more vaccine doses to vaccinate 70 percent of the world. While the vaccine group has received enough pledges to obtain that supply, there are lingering fears over potential interruptions in manufacturing, new variants and waning immunity.

“It is a big range because there are so many unknowns,” Berkley said.

Sarah Owermohle contributed to this report

----------------------------------------

By: Erin Banco, Adam Cancryn and Carmen Paun

Title: Failure to vaccinate poor countries fans fears of uncontrolled outbreak

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/2021/11/23/coronavirus-vaccine-global-pandemic-523218

Published Date: Tue, 23 Nov 2021 04:31:34 EST