All seems calm one spring afternoon on Capitol Hill. Storms whipping up tornadoes are building miles away, but it’s business as usual at the Carol Whitehall Moses Center, Planned Parenthood’s busiest health care facility in the Washington, D.C. region.

Patients scheduled for abortions or routine health care are checking in, getting routed to the clinic’s waiting rooms, labs, nurses’ stations or recovery rooms. The facility provides medication abortion to between 12 to 15 patients a day and 20 to 25 by surgery in the first trimester, according to my guide, Monisha Williams.

“Our patients come from D.C., Maryland and Virginia,” she notes, along with the newcomers flocking to the District that now live in the apartments and condominiums sprouting up around the health care center. And if abortion were banned in the District of Columbia, where would they go? “That’s a question we might have to answer,” says Williams.

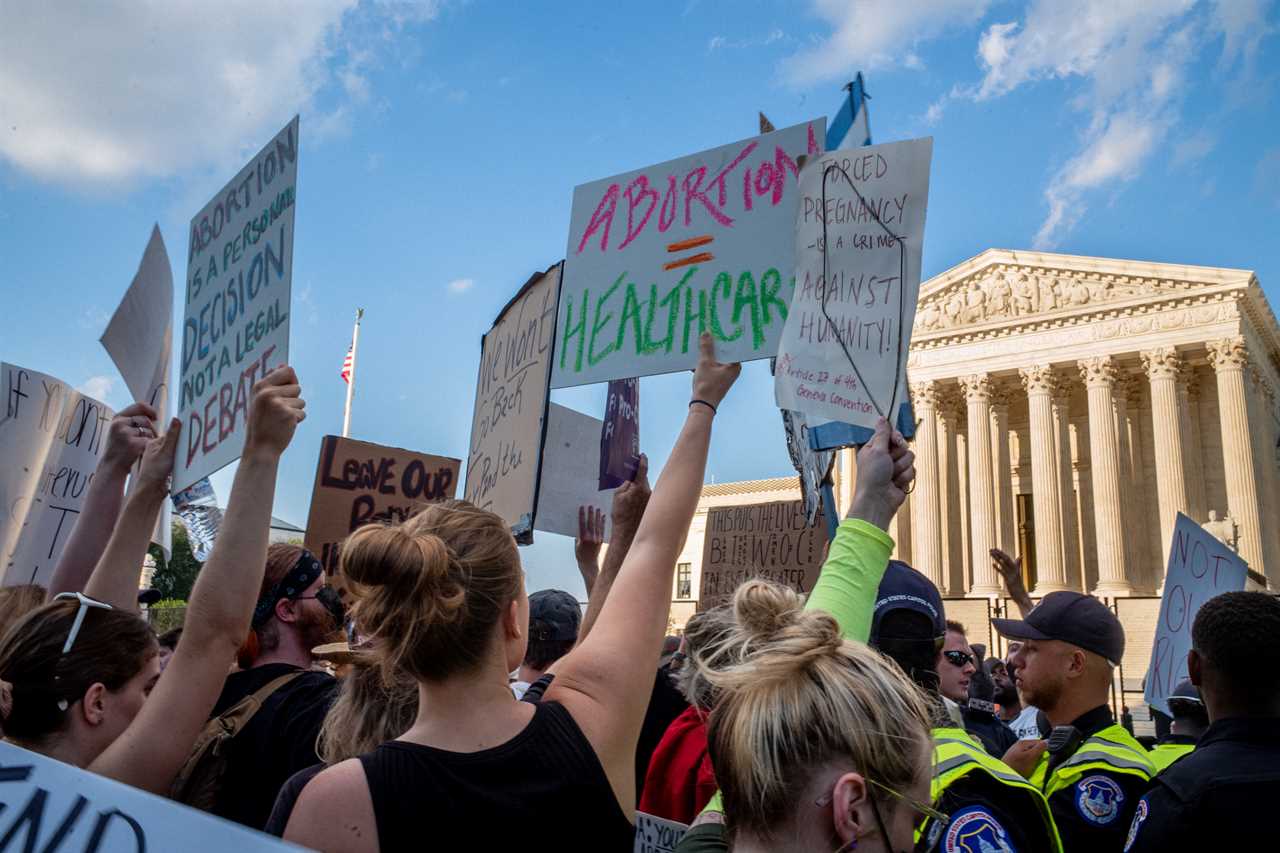

In a move that was both stunning and expected, the Supreme Court last week repealed a woman’s right to abortion under federal law, leaving the matter up to the states. But what happens to those who don’t live in a state? As the nation’s capital, Washington, D.C. is a federal district with limited self-government under the 1973 Home Rule Act. The Constitution bestows Congress with the ultimate power to govern the District.

That power sharing over the past 49 years — though tested annually on hot-button issues like gun rights, marijuana legalization and abortion — has gradually given the District greater autonomy, especially over its budget. But that may be about to change. The hard right turn of the Republican Party, along with the likely prospect that the GOP could win control of at least one house of Congress in November’s midterm elections, has the potential to strip the District of its authority.

Some conservative Republicans are already vowing to introduce legislation banning abortion in D.C. They succeeded years ago at prohibiting D.C. from using federal or local tax dollars to fund abortions. Now one of the most vocal is Rep. Andrew Clyde (R-Ga.). He says that the Supreme Court’s decision overturning Roe v. Wade will be “at the forefront” of his focus next Congress, adding in an email, “I look forward to ending D.C.’s failed experiment of Home Rule once and for all.”

“The District is under attack in every single session, but this is a particularly treacherous moment,” says Democrat Eleanor Holmes Norton, D.C.’s non-voting delegate in the House. “It presents a unique threat to the right to abortions.”

Washington, of course, is one of the bluest spots on the political map. Democrats out-register Republicans by 77 percent to 5. “The GOP is non-existent in the District,” says veteran political operative Tom Lindenfeld. “Even the two most recent office-holders elected as Republicans renounced their association with the party.”

This sets up the prospect of an epic clash between congressional Republicans bent on limiting the right to abortion against a federal city where providing abortions is considered a bedrock right to health care. It also leaves GOP lawmakers open to accusations of hypocrisy, for trumpeting the Supreme Court’s ruling that abortion laws are “returned to the people and their elected representatives.”

“How can they at once say they want to return decision-making back to the localities and proceed to ban abortion in the District of Columbia, where the will of the people clearly comes down on the side of protecting the right to abortion?” asks Dr. Laura Meyers, president and CEO of Planned Parenthood of Metropolitan Washington

Bo Shuff, the longtime executive director of DC Vote, the leading advocacy organization for D.C. becoming the 51st state, is more somber.

“If Congress gets hellbent on banning abortion in D.C.,” he says, “there’s very little the people or officials in the District can do — beyond providing bus trips to Maryland.”

The bus heading north out of the District would take women seeking health care to Montgomery County, Maryland, part of the district represented by Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.).

“Bo is right about that,” Raskin tells me. Without statehood, Congress can exert its will, hypocritical or not.

“It’s unjust and scandalous,” says Raskin, who’s devoted to D.C. self-rule and an advocate of statehood. “But the GOP has always been willing to squash the rights of the people of Washington, D.C.”

There were fewer than 3,000 people in what would become the future capital city when the framers wrote the District Clause into Article 1 of the Constitution, which empowered Congress to “exercise exclusive legislation in all cases whatsoever” over a federal enclave not to exceed 10 square miles. President George Washington chose the site for the capital at the confluence of the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers, up river from his plantation at Mount Vernon. Congress refined the Constitution’s language in the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801, giving itself exclusive jurisdiction over the city.

The Framers and the first president wanted to make sure that the capital was not under the control of a state, but they failed to foresee the thirst for self-governance for the residents of a city that would grow into the hills and farmland rising up from the rivers.

After the Civil War, the District had a brief moment of independence when Congress established a territorial government under Governor Alexander “Boss” Shepherd, who paved the streets but ran up budget deficits. Led by white supremacists in the Senate, Congress took back control in 1890. Since then, committees in the House and Senate controlled the District along with a three-person commission of presidential appointees until the 1960s.

President Lyndon Baines Johnson embraced self-government for D.C. as part of his Civil Rights agenda. His Home Rule legislation failed in 1965, but he replaced the commissioners in 1967 with an appointed council and a mayor. In 1971, Congress granted D.C. a non-voting delegate, elected by its first city-wide vote. Congress then passed the Home Rule Act in 1974, establishing an elected mayor and 13-member council, but Congress kept control of the budget, the courts and review of every local law. Richard Nixon signed the bill into law.

Meanwhile, the city of 3,000 had grown to 800,000 during World War II. In 1957, it became the first majority African American city in the country. The population dropped to under 600,000 after the 1968 riots, but it’s now increasing steadily toward 700,000, the hub of a region of 5.4 million.

No question the muddy village George Washington chose as the seat of government has grown into a fully-functioning, vibrant city. Tourists by the thousands come to visit the Capitol, White House and monuments, of course, but also world class theater, Michelin-rated restaurants, national and local art galleries. Five professional sports franchises play out of D.C.; the Washington Nationals were World Series champs in 2019.

“The District is flourishing,” says Council Chair Phil Mendelson. “We have universal early childhood education, the most progressive income tax in the country, and we balance our budget every year.” It’s not all rosy. Gun crimes are rising, as they are in every major city. Homicides are up. Achievement gaps are glaring in public schools that still fail most poor students. The city’s Black population has steadily decreased at the same time as the cost of housing has skyrocketed in the city. Income disparities between wealthy residents of D.C.’s elite neighborhoods and poor communities east of the Anacostia River are among the widest in the nation.

Congress has grudgingly but gradually loosened its control over the District. It disbanded committees that oversaw D.C. affairs and appropriations. But full statehood has remained out of reach, and taxation without representation lives on. Legal and constitutional challenges loom, but the biggest hurdle is political. Republicans are loath to give the District two senators and a voting member of the House, all of whom would be Democrats. A Democratic-led House has passed statehood bills, but they’ve died in the Senate where at least 60 votes are needed to overcome a GOP filibuster.

“In this climate,” says Raskin, “there will be no statehood as long as the Senate filibuster is in place.”

On the other hand, the Senate filibuster has also protected the right to abortion in D.C. for decades.

“It’s the only thing that really saves us,” Norton says, “even when the Senate has a Republican majority.”

If D.C. was a civil rights matter for LBJ in the 1960s, it became the subject of an anti-abortion crusade for conservative Republicans starting a decade later. Shortly after the Supreme Court legalized abortion in 1973, abortion opponents in the House and Senate attempted to use Congress’ control over the District to curtail or ban abortion in the capital.

North Carolina Sen. Jesse Helms, whose 1973 bill banned use of foreign aid funds for abortions, crusaded every year to apply that standard to D.C., but was rebuffed. In 1986, Helms called D.C. “the abortion capital of the world” on the Senate floor in support of a House bill that would have banned use of federal or local funds on abortions except for women whose life would be endangered by the pregnancy. That bill was also defeated. But in 1988, the Senate adopted an amendment by Robert Dornan (R-Ca.), to ban the use of locally-raised tax dollars for abortions performed in D.C. Indeed, since 1979, Congress has placed some limit or prohibition on D.C.’s ability to use tax dollars to fund abortions, according to the Congressional Research Service.

The nonprofit D.C. Abortion Fund pays for most of the abortions performed in D.C. According to its 2021 annual report, it gave $798,736 in grants to 3,426 recipients.

If the GOP takes the House in the midterm elections, a move to ban abortions in the capital is a given.

Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, who is in line to be the next Republican speaker, stands firmly against abortion rights and backed a 2012 bill to ban abortions in D.C. after 20 weeks. It failed, but McCarthy has shown no respect for Home Rule. He’d also find strong support for banning abortion in D.C. from Republicans on the Oversight and Reform Committee, which has jurisdiction over D.C. and includes numerous anti-abortion lawmakers like Clyde.

“My forthcoming legislation to repeal D.C.’s Home Rule Act will follow and uphold the Constitution, period,” Clyde says by email shortly before the Supreme Court threw out Roe. “Despite the Left’s lie that women have a constitutional right to abortion, the Constitution clearly secures an unalienable right to live — but it does not provide a right to abortion.”

D.C. activists and elected officials are already erecting barricades to defend the District’s right to maintain control of its health care system. Councilmember Brianne Nadeau has introduced a bill to make D.C. a “sanctuary city” for people seeking abortions in D.C., which was immediately backed by nine of 13 council members. Mendelson set aside $50,000 from his re-election campaign to focus on reinstating local funding for abortions. Attorney General Karl Racine, who has sued former President Donald Trump, Big Pharma and slum landlords, has joined the united front to protect abortion rights.

Mendelson dismisses Clyde as “one congressman from Georgia, and he’s not even in the leadership.” But Norton, a fellow member of the committee who could be in the minority by January, takes Clyde more seriously. Is she worried more than usual?

“Absolutely,” she responds. “I’ve got my work cut out for me.”

If Democrats hold on to the Senate in November or at least maintain their power to filibuster, she’ll have to rely on allies like Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.) to shoot down the GOP attacks.

“The senator remains fiercely opposed to any efforts to restrict the rights of DC residents — including a repeal of DC Home Rule,” notes Van Hollen’s office. Opposed, for certain, but Van Hollen can’t say for sure that a Home Rule repeal — or abortion ban — would die in the Senate.

Like LBJ, President Joe Biden has worked virtually his entire life in the District of Columbia, and he’s been an advocate for D.C. autonomy, including statehood. But if an abortion ban or repeal of Home Rule passed both houses of Congress, or was tacked on to another must-pass bill, would he sign?

“If a rider that bans abortion in D.C. arrives on his desk,” asks District political consultant Chuck Thies, “how much political capital would the president want to spend to veto something that affects only the District?”

Biden balked on pot. When faced with the question of whether to protect D.C.’s right to legalize marijuana sales, the president included language in his budgets to support a ban authored by Rep. Andy Harris (R-Md.), a steadfast critic of Home Rule. And though Biden attempted to remove the rider that prohibits D.C. from using tax dollars to fund abortions, Congress reinstated it in the final budget, which he signed, so the ban lives.

Since Jimmy Carter, Democrats in the White House have supported statehood and professed to protect or expand the District’s right to self-government. But they haven’t always followed words with action. At a crucial moment in 1992, Democrats failed to pass a statehood bill when Bill Clinton occupied the White House and the House and Senate had Democratic majorities.

Barack Obama had the same opportunity when he was first elected but chose not to push for statehood. “He has endorsed it,” Norton told the Washington Post in 2016. “He seldom speaks of it.”

In 2011, Obama faced a newly elected Republican House dead set against passing his budget and threatening a shutdown of the federal government. Then-Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio) demanded Obama accept the GOP’s rider prohibiting D.C. from using any taxpayer funds for abortions. Obama stood fast until the 11th hour.

“John, I’ll give you D.C. abortion,” Obama was quoted as saying.

Then-Mayor Vince Gray said D.C.’s “right to govern itself has, once again, been sacrificed on the altar of political expediency.” Days later, Gray and a few council members, including now-Mayor Muriel Bowser, were arrested for protesting on Constitution Avenue near the Capitol. It didn’t stop the deal from going through.

“If the president is facing an opposition Congress,” Shuff says of Biden, “I don’t think he would sacrifice his agenda to save abortion for D.C. women.”

Which brings us to assessing various levels of hypocrisy concerning the District’s right to control its laws and tax dollars.

There’s the low level coming from Pennsylvania Avenue, where Democratic presidents have been strong in talking about statehood and the sanctity of the Home Rule Act but weak in putting political action behind their words.

And there’s the unmistakable brand coming from conservative Republicans crowing about sending laws on reproductive rights back to localities, yet eagerly stepping on them for D.C.’s local residents.

“On that logic,” Raskin says, “the people of the District should decide for themselves.”

Logic aside, Raskin is a constitutional scholar and a political realist. Hypocrisy never stopped a politician, and the odds of securing D.C. statehood any time soon are slim.

“Given the times we’re in,” he continues, “the District joining another state should be examined.”

The term for such a joint venture is retrocession, a giving back of land that Maryland ceded to the government in 1790 to establish the seat of government. It would be complicated, Raskin allows, because voters in D.C. and neighboring Maryland would have to approve such a redrawing of jurisdictions. It would also be heretical, bordering on apostasy, for the majority of District residents who come down hard on independence rather than reliance on another state.

“We’ve dealt with members of Congress from states trying to decide things for the District for a very long time,” says Shuff. “In this case we respectfully disagree.”

But Raskin and Shuff — and Norton and Bowser — agree on one thing: If Congress votes to ban abortion in D.C. now that the Supreme Court has repealed Roe v. Wade and the president chooses not to issue a veto, there’s little the District’s political leadership and residents can do, beyond protest.

“We will put our bodies on the streets and get arrested before we put people on a bus to Maryland,” says Planned Parenthood’s Meyers.

But if the federal government bans abortions in D.C., buses might indeed be necessary: Planned Parenthood’s busy clinic in one of D.C.’s hippest neighborhoods might be forced to relocate to the Maryland suburbs.

----------------------------------------

By: Harry Jaffe

Title: D.C. Is a Democratic Bastion. Republicans Could Ban Abortion There.

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/06/28/dc-abortion-ban-00042675

Published Date: Tue, 28 Jun 2022 03:30:00 EST