The siege on the Beth Israel synagogue reflects a scary new normal.

When an armed man stormed a Texas synagogue on Saturday, taking a rabbi and three worshippers hostage, it seemed fairly obvious that the victims’ identity had something to do with the attack. But in a press conference after all four hostages escaped Beth Israel synagogue in Colleyville, Texas, FBI special agent Matthew DeSarno seemed to deny that, telling reporters the attack’s motive was “not specifically related to the Jewish community.”

DeSarno was attempting to communicate that the hostage taker’s core demand — the release of imprisoned jihadist Aafia Siddiqui — wasn’t about Jews. But interviews with the hostages themselves revealed a clear connection: Their captor believed that a Jewish conspiracy ruled America and that, if he took Jews hostage, he could compel the US to release Siddiqui.

“He terrorized us because he believed these anti-Semitic tropes that the Jews control everything, and if I go to the Jews, they can pull the strings,” hostage Jeffrey Cohen told CNN. “He even said at one point that ‘I’m coming to you because I know President Biden will do things for the Jews.’”

Perhaps DeSarno wasn’t aware of this when he made his comments, which the FBI has since walked back. But major media outlets ran with his line, blaring headlines that downplayed the anti-Semitism at the core of the attack. It was as though the attacker had chosen Beth Israel at random, rather than targeted a Jewish community near where Siddiqui was imprisoned.

The coverage only underscored a creeping sentiment that spread among us last weekend. Many Jews, myself included, already felt like few were paying attention to the crisis in Colleyville as it unfolded over the weekend; that we Jews were rocked by a collective trauma while most Americans watched the NFL playoffs.

This is not a new feeling.

In the past several years, American Jews have been subject to a wave of violence nearly unprecedented in post-Holocaust America. If these anti-Semitic incidents garner significant mainstream attention — a big if — attention to them seems to fade rapidly, erased by a fast-moving news cycle. The root causes of rising anti-Semitism are often ignored, especially when politically inconvenient to one side or the other.

There are always exceptions: In the wake of the Colleyville attack, for example, many Muslims have been particularly vocal allies. But for the most part, the world has moved on. American Jews, on the other hand, cannot — for good reason.

The troubling rise in anti-Semitism

Let’s recount what the past few years have been like for American Jews.

In August 2017, the torch-carrying marchers at Charlottesville chanted, “Jews will not replace us,” as they rallied to protect Confederate iconography. Armed individuals dressed in fatigues menaced a local synagogue — also named Beth Israel — while neo-Nazis yelled, “Sieg heil!” as they passed by.

In October 2018, we saw the deadliest mass killing of Jews in American history: the assault on the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, which claimed 11 Jewish lives. The far-right shooter believed that Jews were responsible for mass nonwhite immigration and wanted to kill as many as he could find in retaliation.

In April 2019, another far-right shooter preoccupied by fears of a Jewish-perpetrated “white genocide” attacked the Chabad synagogue in Poway, California, killing one and injuring three.

In December 2019, New York and New Jersey — the epicenter of American Jewry — were swept by a wave of anti-Semitic violence.

Two extremist members of the Black Hebrew Israelite church, a fringe religion that believes they are the true Jews and we are impostors, killed a police officer and three shoppers at a kosher market in Jersey City. A man wielding a machete attacked a Hanukkah party at a rabbi’s home in Monsey, New York, killing one and injuring four. Orthodox Jews in New York were subject to a wave of street assaults and beatings.

In May 2021, the conflict between Israel and Hamas led to yet another spike in anti-Semitic violence, including high-profile attacks perpetrated by individuals who blamed American Jews for Israel’s actions. In Los Angeles, for example, a group of men drove to a heavily Jewish neighborhood and assaulted diners at a sushi restaurant. The attackers were waving Palestinian flags and chanting, “Free Palestine!”

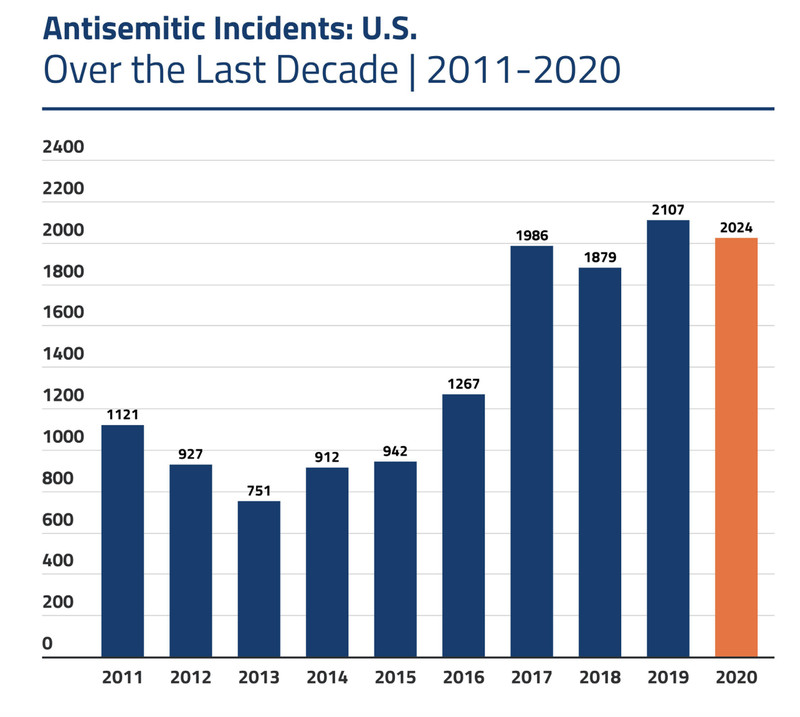

This sort of violence is certainly not the norm. In absolute terms, most American Jews are still quite unlikely to be targeted by anti-Semitic attacks. But both quantitative and anecdotal data suggest that there has been a sustained rise in anti-Semitic activity.

The following chart shows data on anti-Semitic incidents of all kinds, ranging from murders to harassment, from the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), a Jewish anti-hate watchdog. The ADL data, while not perfect, is one of the better sources of information on the topic — and it shows a spike in the past several years.

Anti-Defamation League

The explanation among scholars and experts for this rise tends to focus on Donald Trump’s presidential candidacy and the concomitant rise of the alt-right.

In this telling, Trump’s ascendance shifted the Overton window for the far right, leading to a rise in anti-Semitic harassment and violence. (Trump himself repeatedly made anti-Semitic comments despite having Jewish family.) Recent academic research finds that, in the United States, anti-Semitic beliefs are more prevalent on the right.

The attacks in Pittsburgh and Poway suggest this diagnosis is in large part correct. But the past few years of anti-Semitic violence demonstrate clearly that it’s not the full story.

The Colleyville siege seems to have been perpetrated by a British Islamist. The 2021 attacks seem to have emerged out of anti-Israel sentiment, a cause more associated with the left. The 2019 violence in New York and New Jersey doesn’t really connect to politics as we typically understand it, emerging in part out of a radical subsection of the already-small Black Hebrew Israelite group and local tensions between Black and Jewish residents in Brooklyn.

What this illustrates, more than anything else, is the protean and primordial nature of anti-Semitism — a prejudice and belief structure so baked into Western society that it has a remarkable capacity to infuse newer ideas and reassert itself in different forms.

Today, we are seeing the rise not of one form of anti-Semitism but of multiple anti-Semitisms — each popular with different segments of the population for different reasons, but also capable of reinforcing each other by normalizing anti-Semitic expression.

There is no mistaking the consequences for Jews.

In a 2021 survey from the American Jewish Committee, a leading Jewish communal group, 24 percent of American Jews reported that an institution they were affiliated with had been targeted by anti-Semitism in the past five years. Ninety percent said anti-Semitism was a problem in America today, and 82 percent agreed that anti-Semitism had increased in the past five years.

Synagogues have had to increase security spending, straining often tight budgets that could be spent on programming for their congregants. Measures include hiring more armed guards to patrol services, setting up security camera systems, and providing active shooter training for rabbis and Hebrew school teachers.

Some of this is familiar; there have been armed guards at my synagogue as long as I can remember. But much of the urgency is new. For a community that has long seen America as our haven, a place different in kind from the Europe so many Jews were driven out of, it’s a profoundly unsettling feeling.

The twisting of Jewish suffering

Dara Horn, a novelist and scholar of Yiddish literature, spent 20 years avoiding the topic of anti-Semitism. She wanted to write about Jewish life rather than Jewish death.

But the past few years changed things. In 2021, Horn published a book titled People Love Dead Jews, an examination of the role that Jewish suffering plays in the public imagination. Her analysis is not flattering.

“People tell stories about dead Jews so they can feel better about themselves,” Horn tells me. “Those stories often require the erasure of actual Jews, because actual Jews would ruin the story.”

One of the more provocative examples she mentioned is the oft-repeated poem, attributed to German pastor Martin Niemöller, citing attacks on Jews as one of several canaries in the coal mine for political catastrophe. You’ve probably heard this version of it, or at least seen it on a Facebook post:

First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me

In theory, the message is one of solidarity: What happens to Jews should be of concern to all of us. But Horn argues that there’s a worrying implication to this message, one that instrumentalizes Jews rather than centering us.

“What you’re basically saying is that we should all care when Jews are murdered and attacked because it might be an ominous sign that ‘real people’ might be attacked later,” Horn tells me. “I get that that’s not what it’s trying to say, but it plays into this idea that Jews are just this symbol that you can use for whatever purpose you need.”

In American political discourse, anti-Semitism often gets treated in exactly the way Horn fears: as a tool to be wielded, rather than a problem for living, breathing Jewish people.

Among conservatives, support for Israel becomes equated with support for Jews — to the point where actual anti-Semitism emanating from pro-Israel politicians, from Donald Trump to Marjorie Taylor Greene, is treated as unimportant or excusable. The Jewish experience becomes flattened into a narrative of “Judeo-Christian” culture under shared threat from Islamist terrorism, eliding the ways in which America’s mostly liberal Jewish population feels threatened by the influence of political Christianity on the right.

Menahem Kehana/AFP/Getty Images

Colleyville is already being deployed in this fashion. In a public letter, Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO) turned an attack on Jews into an attack on admitting Afghan refugees.

“I write with alarm over reports that the Islamic terrorist who took hostages at a Jewish synagogue in Texas this past weekend was granted a travel visa,” Hawley claims. “This failure comes in the wake of the Biden Administration’s botched withdrawal from Afghanistan and failure to vet the tens of thousands who were evacuated to our country.”

Never mind that the attacker came from Britain, not Afghanistan. Never mind that he was not a refugee. Never mind that Jews are some of the staunchest supporters of refugee admittance in the country, owing to our own experiences as refugees after the Holocaust.

There are also problems like this on the left, albeit less common among mainstream political figures.

Incidents of anti-Semitic violence are mourned and then swiftly deployed in partisan politics, turned into a brief against MAGA America, rather than serving as an opportunity to confront the way many progressives fail to take anti-Semitism seriously as a form of structural oppression. Similarly, Jewish concerns about anti-Israel rhetoric crossing the line into anti-Semitism are ignored or even dismissed as smear jobs. I have had brutal, sometimes even angry conversations with progressive friends and acquaintances on this very topic.

The throughline here is that Jews don’t own their stories; that anti-Semitism means what others want it to mean. And that’s when people pay attention to anti-Semitism at all, which they often do not — except for the few days after incidents like Colleyville.

A common refrain from Jews I know during and after the Colleyville standoff was a sense of total alienation, that they were glued to their phones and TVs while most others had no idea that American Jews were in crisis. It wasn’t that we had been made into object lessons for others, at least not yet; it was that our suffering was barely worth noticing.

What American Jews need from mainstream American society right now is to be listened to, for our fears about rising anti-Semitism to be heard and, once heard, taken seriously on their own terms.

This does not require the false assumption of a monolithic Jewish community, where all of us agree on how to tackle anti-Semitism. What it does require is a mental reorientation among America’s non-Jews: a willingness to reckon with the fact that anti-Semitism remains a meaningful force in American society, one that requires a response both unfamiliar and politically uncomfortable.

----------------------------------------

By: Zack Beauchamp

Title: The world has moved on from Colleyville. American Jews can’t.

Sourced From: www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/22889932/beth-israel-synagogue-hostage-attack-terrorism-antisemitism

Published Date: Thu, 20 Jan 2022 11:30:00 +0000