The U.S. and its allies around the world have imposed a long list of harsh sanctions on Russia in response to its aggression in Ukraine. Russian banks have been removed from SWIFT, the assets of Russia’s central bank have been frozen, the Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline has been canceled, export controls have been levied and so on. Although these sanctions are designed to hurt Vladimir Putin, they also hurt us and the global economy. Energy prices have soared, for example, and bank stocks have tanked.

But it’s not like sanctions will prevent Putin from invading Ukraine — that ship has sailed. “As satisfying as it might feel in the moment, ‘imposing costs’ cannot be an end in itself,” political scientist Washington Post","link":{"target":"NEW","attributes":[],"url":"https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2022/03/01/what-is-plan-behind-sanctioning-russia/","_id":"00000180-4b8b-d3c7-a3b5-efefb47e0006","_type":"33ac701a-72c1-316a-a3a5-13918cf384df"},"_id":"00000180-4b8b-d3c7-a3b5-efefb47e0007","_type":"02ec1f82-5e56-3b8c-af6e-6fc7c8772266"}">Daniel Drezner argued recently in the Washington Post. “Sanctions should be a means to achieving a larger end.” And in our current moment, the sanctions don’t appear to be persuading Putin to de-escalate — perhaps even risking the opposite. Why then, reasonable people may ask, should we continue to pay the cost to sanction Russia?

The point of sanctioning is that, if we don’t, the norm against territorial incursions will collapse. Preserving this norm — and working to prevent similar abuses in the future — is worth the cost of sanctioning. But why is norm collapse an inexorable consequence of failing to sanction? Fortunately, a bit of game theory can help us answer this question.

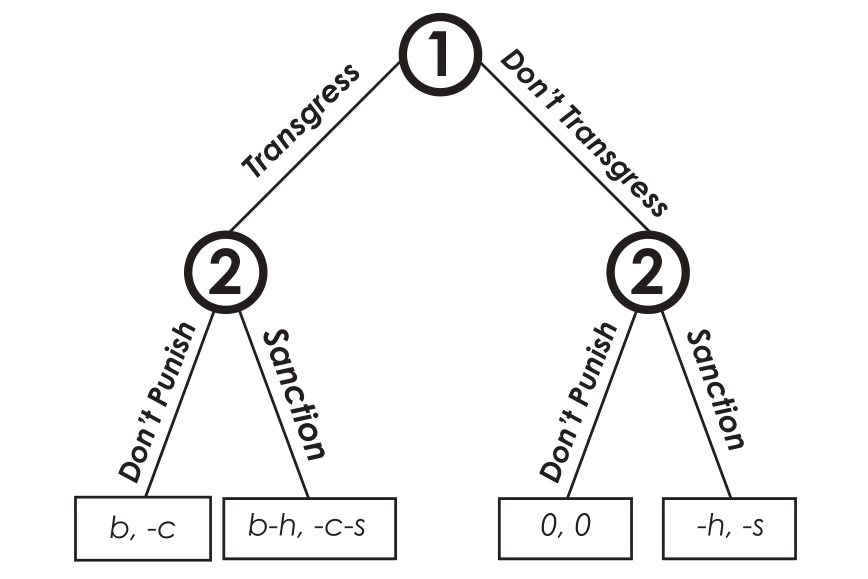

Let’s call this the Repeated Sanctions Game, which has two players. In each round of the game, Player 1 (i.e., an adversary such as Putin) chooses whether to transgress, then Player 2 (i.e., NATO) chooses whether to sanction. Transgressing benefits Player 1 (Putin would like to annex Ukraine) but costs Player 2 (NATO would prefer that Ukraine be free). As in real life, sanctioning is costly not just to Player 1 but also to Player 2, who might prefer not to, for example, suffer higher prices or lose revenue from Player 1’s products and businesses as a result. Then Player 2 plays the game again and again — perhaps with the same Player 1, perhaps with another (Putin now, maybe Xi next time).

For Player 2 to deter future transgressions in this game, she would have to threaten to sanction Player 1 whenever he transgresses. This threat has to be credible, otherwise Player 1 will simply call Player 2’s bluff. Player 2 must, if called upon, reliably follow through on her threat.

How can this be worth it for Player 2, given that, as already acknowledged, sanctioning is costly? To see, we must factor future expectations into the cost-benefit calculation. When a transgression isn’t met with sanctions, everyone would reasonably expect that future transgressions may also go unpunished. This is the norm collapsing. So long as Player 2 cares enough about the costs of all those future transgressions, she’ll prefer the collateral costs of punishing the transgressor today to increasing the likelihood of future transgressions. It’s not preventing or stopping the current transgression that’s motivating Player 2 to sanction, it’s the fact that without sanctions as a response, there will inevitably be more transgressions.

Indeed, even if Putin isn’t acting rationally, it makes sense for NATO and others to impose sanctions. That’s because what the international community is really trying to avoid is other, more rational actors, such as Putin’s eventual successor or Xi, inferring that future invasions will not be punished.

The idea that failing to sanction must carry a cost comes from the game theory concept known as “subgame perfection.” This term just means that players’ strategies must be optimal in any part of the game. In this case, it’s being applied to Player 2, and specifically to the fact that she’s threatening to sanction. Subgame perfection tells us that there has to be something that makes it worthwhile for her to follow through. Something like the collapse of the norm.

This theoretical result lines up with how our intuitions about norms and vengeance actually work. It’s what Hitler expected after Chamberlain failed to defend Czechoslovakia, and it’s probably what Putin expected after the West failed to sufficiently punish his 2014 foray into Crimea. In the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine, both sides engage in risky retaliation, very likely — and sometimes explicitly — out of the fear that if they don’t, the other side will simply walk all over them.

Game theory can help clarify why imposing costs on a transgressor is necessary even when it comes at a cost to oneself too — and seems unlikely to achieve any larger end in the immediate conflict. Tools like “subgame perfection” are also useful for understanding why our seemingly perverse intuitions work the way they do — and that they’re not as perverse as they might initially seem.

So, yes, it’s true that sanctions will hurt our economy, and it’s true that they may even push Putin to further escalate Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. That’s all really bad, but it’s not as bad as a future where national sovereignty is not respected. For the norm against territorial incursion to survive, everyone must forever know that we are willing to pay the cost to sanction.

----------------------------------------

By: Moshe Hoffman and Erez Yoeli

Title: Opinion | The Sanctions Against Russia Might Not Stop Putin. They’re Not Meant To.

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/04/21/russia-sanctions-game-theory-00026566

Published Date: Thu, 21 Apr 2022 03:30:00 EST

Did you miss our previous article...

https://consumernewsnetwork.com/politics-us/what-is-the-hottest-trend-on-tiktok