In 2011, a former Pentagon strategist named Phillip Karber who was teaching at Georgetown University asked his students to study the Chinese tunnel system known as the “underground great wall.” The tunnel’s existence was well-known, but its purpose was not. Karber’s students turned to commercial imagery, blogs, military journals, even a fictional Chinese television drama to get answers. They concluded the tunnels were probably being used to hide 3,000 nuclear weapons. This was an astronomical number, about 10 times higher than declassified intelligence estimates and other forecasts of China’s nuclear arsenal.

The shocking findings were featured in the Washington Post, circulated among top officials in the Pentagon, and led to a congressional hearing. They were also incorrect.

Experts quickly found egregious errors in the study. A Harvard researcher found that Karber’s students based the 3,000 weapon number on an American intelligence projection from the 1960s, assumed it was accurate, and then just kept adding weapons at a constant rate of growth. Apparently, they did not take seriously more recent declassified intelligence estimates that China probably had no more than 200 to 300 warheads. And Karber’s estimates for the amount of plutonium needed for the weapons were based on sketchy sources using even sketchier ones: The study cited Chinese blog posts that were based on a plagiarized grad school essay from 1996, which in turn relied on a single anonymous post on the site Usenet. The plutonium sourcing was “so wildly incompetent as to invite laughter,” wrote nonproliferation expert Jeffrey Lewis.

This is the radical new world of open-source intelligence — where crises move faster, information is everywhere and anyone can play. Intelligence isn’t just for governments anymore, thanks to three major trends over the past several years: the proliferation of commercial satellites, the explosion of Internet connectivity and open-source information available online, and advances in automated analytics like machine learning. These changes have touched every part of the intelligence landscape. In particular, they’ve given rise to a host of non-governmental detectives who track some of the most serious and secret dangers of all: nuclear weapons.

The world of open-source nuclear sleuthing is wide open to anyone with an Internet connection. It draws people with a grab bag of backgrounds, capabilities, motives and incentives — from hobbyists to physicists, truth seekers to conspiracy peddlers, profiteers, volunteers and everyone in between. Many are former government officials with years in the field, but others are amateurs with little or no experience. There are no formal training programs, ethical guidelines or quality control processes. And errors can go viral; nobody loses their job for making a mistake.

The open-source revolution has been lauded for disrupting and democratizing the secretive world of intelligence. There is no doubt that open-source intelligence is invaluable and that spy agencies must find new ways of harnessing its insights. But the news is not all good. Citizen-detectives also generate risks. From the most obvious risk of getting it wrong, to harder-to-see downsides like derailing diplomatic negotiations by publicly revealing sensitive findings, the U.S. intelligence community needs to pay attention to the potential dangers of open-source intelligence as it adapts its spycraft to the digital age.

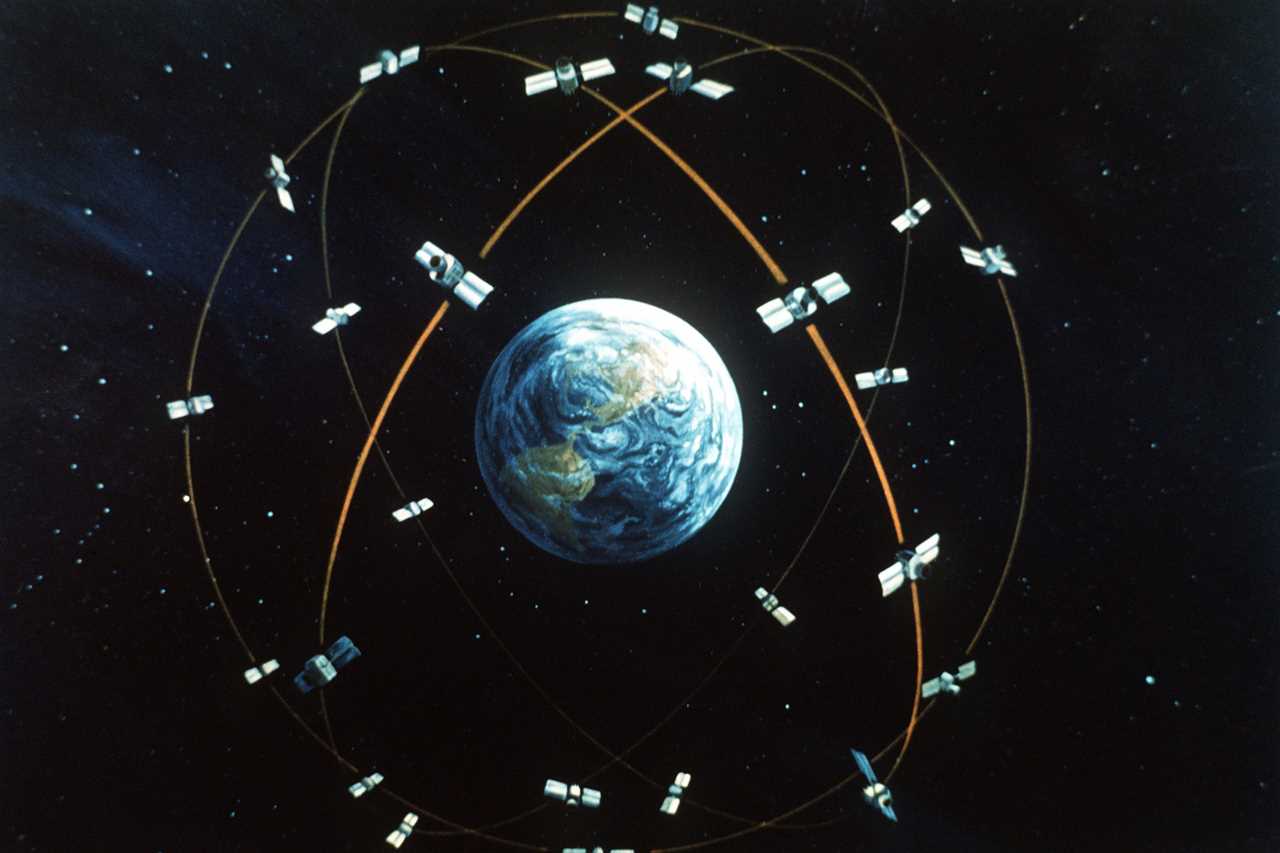

Tracking nuclear threats used to be a superpower business, because much of it was done from space and governments were the only ones with the know-how and money to build sophisticated satellites. Today, the commercial satellite industry offers low-cost eyes in the sky to anyone who wants them. Already, 3,000 active satellites orbit the earth; according to some estimates, by 2030, there will be 100,000. While spy satellites still have greater technical capabilities, commercial satellites are narrowing the gap, with resolutions that have improved 900 percent from just 15 years ago. And more satellites mean the same location can be viewed multiple times a day to detect small changes over time, giving a dynamic view of unfolding threats.

Connectivity is changing the spy business, too, turning everyday citizens into intelligence producers, collectors and analysts — whether they know it or not. Each day, millions of people photograph and videotape the world around them to share online. Apps track all sorts of data, including the bars we visit and the places we jog. Community data sharing sites like OpenStreetMap allow users to post their GPS coordinates from their phones. These capabilities offer new clues and tools for non-governmental nuclear sleuths, who can synthesize bits of information to reveal more than anyone imagined was possible.

Technology is also transforming analysis. Downloadable 3D modeling applications make it easy for citizen-sleuths to imagine faraway places with remarkable accuracy. And increases in computing power and available data have spawned machine learning techniques that can analyze massive quantities of imagery or other data at machine speed. For those analyzing nuclear threats, machine learning can help detect changes over time at known missile sites or suspect facilities. In 2017, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency asked researchers at the University of Missouri to develop machine learning tools to see how fast and accurately they could identify surface-to-air missile sites over a huge area in Southwest China. The team developed a deep learning neural network (essentially, a collection of algorithms working together) and used only commercially available satellite imagery with 1-meter resolution. Both the computer and the human team correctly identified 90 percent of the missile sites. But the computer completed the job 80 times faster than humans, taking just 42 minutes to scan an area of approximately 90,000 square kilometers (about three-quarters the size of North Korea).

All of these developments have given rise to an ecosystem of nuclear sleuths that looks very different from the classified world of intelligence agencies. Open-source researchers include academic experts and employees of large multinational corporations that do business around the globe or smaller firms that operate satellites. Others are just private individuals who enjoy scouring the web and sharing their findings with like-minded hobbyists. And some intend to deceive.

This is the Wild West compared to the classified world. In spy agencies, participation requires security clearances and adherence to strict government policies. Analysts come with narrower backgrounds but higher average skill levels. They work inside cumbersome bureaucracies, but have access to training and quality control. While motives in the open-source world vary, in the government the mission is generally uniform: giving policymakers decision advantage. One ecosystem is more open, diffuse, diverse and faster-moving. The other is more closed, tailored, trained and operates much more slowly.

On the positive side, citizen-sleuths provide more hands on deck, helping intelligence officials and policymakers identify fake claims, verify treaty compliance and monitor ongoing nuclear-related activities. They can show that what looks like an ominous nuclear development by an adversarial nation is actually nothing to worry about. For example, open-source researchers demonstrated that a cylindrical foundation in Iran that might have indicated the beginnings of a nuclear reactor was actually a hotel under construction, and that an Israeli television report supposedly showing an Iranian missile launch pad big enough to send a nuclear weapon to the United States was just a massive elevator that resembled a rocket in a blurry image.

Non-governmental nuclear sleuths can also do the opposite: surface clandestine developments that might not otherwise be discovered. In 2012, my Stanford colleagues Siegfried Hecker and Frank Pabian determined the locations of North Korea’s first two nuclear tests using commercial imagery and publicly available seismological information — assessments that proved highly accurate when North Korea revealed the test locations six years later.

Another example came in July 2020 in Iran, when a fire started during the middle of the night with flames so bright, a weather satellite picked them up from space. Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization initially downplayed the fire as a mere “incident” involving an “industrial shed” under construction. The agency even released a photo showing a scorched building with minor damage.

Unconvinced, David Albright and Fabian Hinz, researchers at two different NGOs, began hunting. Using geolocation tools, commercial satellite imagery and other data, each separately concluded the Iranians were lying. The shed was actually a nuclear centrifuge assembly building at Natanz, Iran’s main enrichment facility. The fire was large, almost certainly produced by an explosion, and possibly the result of sabotage.

Albright and Hinz took to Twitter. By 8:00 a.m., the Associated Press was running their analysis. By mid-afternoon, the New York Times was too. By nightfall, as mounting evidence pointed to the possibility of Israeli sabotage, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was asked about it in a press conference. “I don’t address these issues,” he curtly replied.

The entire incident unfolded in a single day. Neither Albright nor Hinz worked in government or held security clearances. The intelligence was collected, analyzed and disseminated without anyone inside America’s sprawling spy agencies. And because it was all unclassified — the researchers didn’t have to worry about protecting intelligence sources and methods — it could be shared, drawing public attention to Iran’s cover-up and forcing questions about Israel’s role.

Because of its many successes, and the appealing notion of democratizing the search for truth, open-source intelligence is frequently discussed with a kind of breathy optimism. “The people’s panopticon: Open-source intelligence comes of age,” declared the Aug. 7, 2021 cover story of The Economist. Bellingcat, the fascinating organization of global volunteer detectives best known for uncovering Russian dirty deeds and Syrian atrocities, personifies this hopeful view of intelligence-for-global-good. Its founder, Eliot Higgins, describes Bellingcat as “an intelligence agency for the people,” an “open community of amateurs on a collaborative hunt for evidence.”

Yet the open-source ecosystem brings risks that are significant and often neglected. Open-source intelligence is easy to get wrong because good analysis takes training. Interpreting satellite imagery, for example, requires considerable skill and experience to know how shapes, shadows, textures and angles can distort or delineate objects seen from directly overhead. And for all the celebration of organizations like Bellingcat, there are other open-source organizations that traffic in shoddy analysis and pet theories, play fast and loose with evidence, and inject errors into the policy debate — sometimes inadvertently, sometimes deliberately.

In 2001, respected British journalist Gwynne Roberts ran a bombshell story in the Sunday Times reporting that Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein had secretly tested a nuclear weapon back in 1989. Roberts’ three-year investigation began late one night in northern Iraq, when a mysterious visitor calling himself Leone came to Roberts’ hotel room, offering sketches of bomb designs, a photograph of a warhead he claimed Iraq had bought from Russia and details of Saddam’s WMD program. Leone even gave the exact time and location of the alleged nuclear test: Sept. 19, 1989, at 10:30 a.m., at an underground site 150 kilometers southwest of Baghdad.

To report out the tip, Roberts went high-tech, buying commercial satellite images of the test site before and after the claimed date and having them analyzed by Professor Bhupendra Jasani of King’s College London. Jasani’s analysis found all sorts of evidence confirming Leone’s claim, including a wide tunnel running under a lake, exactly as Leone had described, and a railway line with roads leading to a huge rectangular structure — a shaft entrance. Jasani also found evidence of an unusually sensitive military zone, an army base with 40 buildings. “If you wanted to hide something, I guess this is exactly what you would do,” the professor said.

All of it turned out to be wrong, even the smoking gun satellite imagery. Frank Pabian, former chief inspector for the International Atomic Energy Agency in Iraq and one of the Stanford researchers who would later discover the North Korean test site, reviewed the satellite images and found no evidence the area had ever been used to conduct an underground test. The tunnel was actually an agricultural area served by a natural spring. The rail lines were a dual-lane highway. The large rectangular structure was an irrigated field, and the military zone was actually just two conventional ammunitions storage facilities and some typical storage bunkers. Pabian and forensic seismologist Terry Wallace also found extensive seismological evidence that further discredited the Sunday Times story.

Still, Roberts’ investigation appeared on BBC, where a write-up can still be found online, uncorrected — years after additional evidence showed conclusively that Saddam tried but never succeeded in developing a nuclear bomb. Leone and his motives remain a mystery.

That’s just the honest mistakes. The non-governmental intelligence ecosystem also increases the risks of deliberate deception. In fact, it’s already happened. In 2015, an Iranian dissident group calling itself the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI) tried to derail international negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program by claiming that a company named Matiran was housing a secret nuclear facility in its Tehran office basement. NCRI’s evidence included satellite imagery of the secret facility as well as photographs of its hallways and a large lead-lined door to prevent radiation leakage.

Within a week, Jeffrey Lewis’ team at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies showed that all of this evidence was fabricated, including photographs of the lead door — which turned out to be copied from an online promotional photograph of a warehouse that had nothing to do with illicit nuclear activities. Matiran was a real company, all right, but it wasn’t building nuclear weapons in its basement. It specialized in making secure documents like national identification cards. In this case, expert open-source detectives were able to detect the hoax. But the fake imagery could just as well have deceived other sleuths working quickly, lacking specialized training, and primed to see satellite imagery and other publicly available data as evidence of the truth hiding in plain sight.

Matiran was a relatively low-tech deception operation. The rise of social media and advances in artificial intelligence are making deception easier to pull off and harder to detect. Russia’s interference in the 2016 American presidential election included widespread use of phony social media accounts, sowing divisions and seeking to tilt the outcome of the election. Meanwhile, advances in artificial intelligence have given rise to “deepfakes,” or digitally manipulated audio, photographs and videos that are highly realistic and difficult to authenticate. Deepfake application tools online are now widely available and so simple to use, high school students with no coding background can create convincing forgeries.

It isn’t hard to see how these technologies could be used to manipulate people eagerly searching the Internet for evidence of clandestine nuclear activities. Using cheap satellite imagery, deepfakes and weaponized social media, foreign governments — or their proxies, or just individuals looking to make trouble — will be able to inject convincing false information and narratives into the public debate. Imagine a deepfake video depicting a foreign leader secretly discussing a nuclear weapons program with his inner circle. Although the leader issues vehement denials, doubt lingers — because seeing has always been believing and nobody can be completely sure whether the video is real or fake.

Even truthful information can be dangerous in the open-source world — making adversaries wise to weaknesses in their camouflage and concealment techniques, or making crises harder to manage for diplomats and officials. In 2016, Dave Schmerler, another researcher at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, was able to measure the size of North Korea’s first nuclear device (called a “disco ball”) and locate the building where it was photographed by using objects in the room as telltale markers. The next North Korean photo of a warhead was taken in a completely white room with nothing to measure. Whether Schmerler’s research prompted the change is impossible to know. But in the world of intelligence, any time new monitoring methods are revealed, countermeasures are likely to follow, making future monitoring more difficult. Short-term intelligence gains revealed by well-meaning private citizens could unwittingly generate far greater losses in the long term.

Revealing accurate information can also escalate international crises by forcing action too soon and making it harder for each side to walk away with a win. In moments of crisis and sensitive negotiations, policymakers rely on useful fictions to buy time and save face, giving one or both sides a way out. When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, the CIA began arming the Afghan Mujahideen. The Soviets knew it, and the Americans knew the Soviets knew. But the fiction kept a proxy war from becoming a superpower war with the potential for nuclear escalation. Fig leaves can be useful.

But the more third parties generate transparency, the harder it is for leaders to wield these useful fictions to manage conflict. Imagine a Cuban missile crisis unfolding today. An open-source sleuth discovers the Soviet nuclear buildup by analyzing commercial satellite imagery and tweets about it. Now both President Kennedy and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev are backed against the wall, publicly. The pressure is intense for both to take forceful action.

The two key ingredients to resolving the actual Cuban missile crisis in 1962 weren’t speed and openness — which is what open-source intelligence provides — but time to think and secrecy to compromise. Kennedy and his advisers had 13 days to weigh their options. Their declassified deliberations show that had Kennedy been forced to decide immediately, he would have opted for an air strike that could well have led to nuclear war. Secrecy, too, proved pivotal, giving Kennedy and Khrushchev room to compromise and ultimately resolving the crisis with a missile trade so closely held, nobody knew about it for the next two decades. It’s easy to imagine how well-meaning “fact-checking” in real time by non-governmental nuclear sleuths could have derailed that agreement, escalating a superpower standoff already teetering on the brink of global nuclear war.

The open-source revolution offers tremendous promise for detecting nuclear threats. But peril always rides shotgun with promise. For the CIA and the other 17 agencies of the U.S. intelligence community, this is a moment of reckoning. Secrets once conferred a huge advantage, but increasingly, that advantage belongs to open-source information. To succeed, spy agencies will need to operate differently: giving open-source intelligence much greater focus and attention, harnessing new technologies and tradecraft to improve their own collection and analysis, and understanding that open-source intelligence isn’t just intelligence. It’s an entirely new ecosystem of players with their own motives, capabilities, dynamics and — importantly — weaknesses.

----------------------------------------

By: Amy Zegart

Title: Opinion | Meet the Nuclear Sleuths Shaking Up U.S. Spycraft

Sourced From: www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/01/19/nuclear-sleuths-shaking-up-us-spycraft-527319

Published Date: Wed, 19 Jan 2022 04:30:36 EST